| By Gale Staff |

February 2024 marks the 48th anniversary of Black History Month—and an exciting opportunity for educators to broaden students’ horizons beyond the current cultural canon of Rosa Parks, Martin Luther King, Jr., and Malcolm X.

Gale In Context: Biography brings the legacies of these luminaries to light, highlighting their indelible impact on the world with curriculum-aligned, multimodal content created with ease of access in mind. Students can explore more than 640,000 biographical profiles, including hundreds of black changemakers with intriguing stories to tell.

Bessie Coleman

Charismatic and spunky, Bessie Coleman (1892-1926) was born with her eye on the sky, driven by an irrepressible urge to soar beyond the confines of race, gender, and the Earth itself. Bessie, known as Queen Bess, grew up facing a world that seemed to tell her “No” at every turn.

No woman could fly.

No person of color could fly.

The privilege of piloting was one reserved for white men.

Yet, Coleman had the gumption to never take no for an answer, even after flight schools across America denied her application.

Instead of resigning herself to life on terra firma, she worked as a manicurist and maid to fund her dreams, heading across the Atlantic to the Caudron Brothers School of Aviation. On June 15, 1921, she earned her wings from the Fédération Aéronautique Internationale and became the first black woman and first woman of Native American descent to obtain a pilot’s license.

Coleman’s first American air show took place on September 3, 1922, and so began a tragically short career as an ace pilot. Over the next few years, she sought out funds to achieve her new dream of opening a flying school for people of color in the United States, and eventually purchased her own plane—a poorly maintained Curtiss JN-4D Jenny.

She intended to perform with this plane in Jacksonville, Florida, on May 1, 1926. However, during a rehearsal flight the day before, in which she was seated in the rear cockpit, the plane went into a sudden spin, throwing Coleman to her death. Her co-pilot lost his life when the plane crashed. It was later discovered that the cause of mechanical failure was a wrench that had slipped, jamming the gearbox—a problem that would have been prevented had Coleman not been relegated to using a then-obsolete plane model.

Queen Bess’s dream did eventually come true with the creation of Bessie Coleman Aero Clubs and Bessie Coleman Aviators Club, both of which welcomed pilots of any race and gender to fly in honor of this pioneering aviator who refused to let the circumstances of her birth stop her from having her head in the clouds.

Paul Robeson

Polyglot, activist, scholar, singer, actor, and athlete could all be used to describe Paul Robeson (1898-1976). Yet, any single identifier is insufficient to explain his legacy, which Barry Gewen describes as “an artist of unassailable gifts and achievement who was brought low through his own political obtuseness.”

After earning a law degree from Columbia, Robeson opted out of the legal field due to the intense discrimination he experienced before he even got his foot in the door. Instead, he pursued his passion for theater in London, earning countless accolades for his deep bass-baritone as he crooned through folk music and spirituals from across cultures. So impressive was Robeson’s voice that he was eventually cast in the role of Joe in the 1936 film adaptation of Show Boat, during which he performed his rendition of “Ol’ Man River.”

During his time as a student enrolled in the University of London’s School of Oriental and African Studies in the mid-30s, he aligned himself with anti-imperialist organizations.

He was particularly drawn to the Soviet Union’s anti-racist sentiments and support of the “Scottsdale Nine” boys with literature like “Gedenk vegn Skotsboro!” or “Remember Scottsboro!” a pamphlet that “called on Soviet citizens to join protest campaigns… against the execution of the accused… [and] denounced the trial and ‘lynch justice’ that prevailed across the American Black Belt.” Robeson also aligned himself with the Republicans against the fascism of the Nationalists during the Spanish Civil War, using his performances of “Ol’ Man River” to defy the narrative of the defeated, resigned black man with lyrical changes that painted a more defiant picture.

Upon his return to America, he became the target of McCarthyism due to his civil rights activism, particularly his demand for President Truman to enact anti-lynching legislation—which was only recently passed in 2022 with The Emmett Till Antilynching Act— and the formation of the American Crusade Against Lynching in 1946. Robeson also became more vocal in his support for unions, the Communist Party, and the Soviet Union. He was blacklisted and his passport revoked, making it impossible for him to continue his career in the entertainment industry.

Posthumous sentiments have been much kinder. Today, you can find his name on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, his likeness on an official USPS stamp, and his life the subject of a play by Miriam Jensen Hendrix.

Jane M. Bolin

In an era when white men had an indomitable grip on the legal field, Jane Matilda Bolin (1908-2007) broke barriers to become the first black woman to graduate from Yale Law School in 1931. From there, Bolin continued to blaze the trail with her appointment as the first black female judge in the United States by New York City Mayor Fiorello La Guardia. Her swearing-in ceremony was momentous, taking place at the 1939 “World of Tomorrow” World’s Fair.

Judge Bolin’s four decades of work in the Family Court of the State of New York saw her become an unrelenting advocate for children, people of color, and those living in poverty. Two of her most celebrated achievements in her time at the bench include ending the practice of race-based probation officer assignments and racial discrimination in publicly funded childcare agencies.

Bolin was revered not only for her activism and advocacy but also for her remarkable sense of poise, dignity, and patience in the face of some of what her father, Judge Faius C. Bolin, described as “… the most unpleasant and sometimes grossest kind of human behavior.” Even in the face of cases that involved juvenile violent crimes, domestic violence, and child neglect, she chose to preside over her courtroom with a steadfast determination to dispense justice equitably, regardless of socioeconomic status or race, going so far as to leave her judge’s robes in her chambers to put her young litigants at ease.

After her retirement in 1979 at age 70, Bolin remained active in her community as a volunteer reading teacher in New York Public Schools and as a member of the Regents Review Committee.

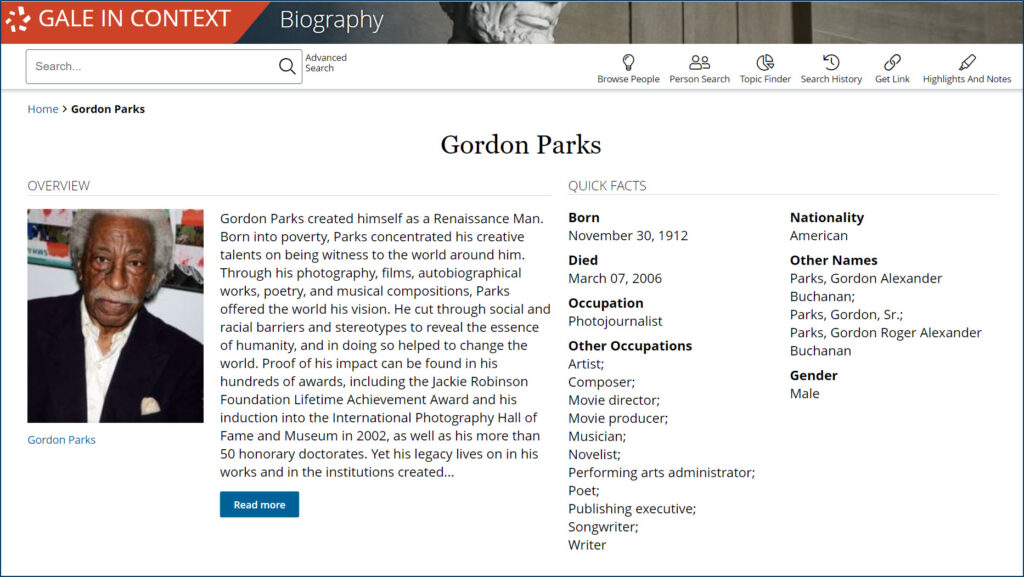

Gordon Parks

When Gordon Parks (1912-2006) first day laid hands on a Voigtlander Brilliant purchased from a Seattle pawnshop in 1937, he had no idea that this secondhand camera would spark a passion for capturing the black cultural zeitgeist of the 20th century through photography, film, dance, and literary works. And so, with camera in hand, Parks began his rise from pest-infested tenement buildings and working as a porter to becoming the first black photographer featured in Life and Vogue magazine.

Parks cut his teeth in St. Paul, Minnesota as a photographer for Frank Murphy’s Department Store and two local, black-owned newspapers before moving to Chicago, where he spent time between contracted work and capturing the reality of life in the slums. By 1941, his documentary photography had earned him a Julius Rosenwald Fellowship and, with it, the opportunity to work for Roy Emerson Stryker in Washington, DC.

On his first day in Washington, Parks shot perhaps his most iconic photograph, “American Gothic,” featuring Ella Watson, a black cleaning lady, standing before the American flag with broom and mop in hand. It was a visual revolt, forcing audiences to confront the juxtaposition of the American dream and the cruelness of many people of color’s inability to ever attain it.

Parks was so successful at capturing evocative images that he rose through the ranks of the Office of War Information, Vogue, Glamour, Standard Oil, and by 1948, Life. His first foray with the renowned periodical saw Parks spending time with Harlem gang leaders, capturing the humanity in the daily struggle for survival amongst the impoverished youth in urban America. In his 20 years with Life, he found himself at the frontlines of the Civil Rights movement, weaving himself into the narratives of activists like Malcolm X, who mentions Parks in his autobiography.

Photography wasn’t Park’s only passion. He composed a ballet based on Martin Luther King Jr.’s life and created documentaries. He wrote essays, novels, and poetry and curated traveling exhibits of his work.

As a genuine Renaissance man, there was seemingly no medium that Parks couldn’t transform into a statement about black lives in America. He even holds the title of being the first black director of a major Hollywood film with Shaft (1971), a movie that reclaimed the blaxploitation genre, redefining the portrayal of black protagonists and claiming its place as a cult classic.

His work on lifting black culture into the mainstream consciousness and subverting stereotypical depictions of what being black means continues to live on. After his passing in 2006, he was recognized by the International Photography Hall of Fame and Museum, the Jackie Robinson Foundation Lifetime Achievement Award, and through a curated collection of donated memorabilia housed at the Library of Congress.

Combine Gale In Context: Biography With For Educators

Our goal at Gale is to help educators have the greatest impact on students with diverse, unbiased content you can trust. Skip the vetting process and spend more time engaging with students in more meaningful ways with Gale In Context: For Educators.

Gale In Context: Biography offers videos, newspaper articles, photographs, and more compiled into comprehensive profiles available at your students’ fingertips, not just during Black History Month but throughout the entire school year.

If you’re not yet a subscriber, learn more or request a trial.