| By Gale Staff |

From Hollywood to history books, the stories of Native Americans have long been marginalized, misrepresented, and misunderstood. Observed each November, Native American Heritage Month asks that we actively challenge this imbalance through recognition of the “significant contributions the first Americans made to the establishment and growth of the U.S.”

In the classroom, this annual celebration of Indigenous peoples allows educators to dedicate time to exploring the rich, often overlooked aspects of Native American history. To do so, however, classrooms need access to resources that offer a fuller, more nuanced view of history. The Native American Heritage Month topic page available through Gale In Context: High School provides a wealth of educational materials that facilitate the presentation of Native American contributions in their full complexity, from pre-colonial times to the present day.

Gale In Context: High School provides a platform for Native American voices and stories, giving students the tools to engage critically with history in all its complexity. Many of our materials feature the authentic voices of Indigenous scholars, leaders, and creators, so students can engage deeply with Native cultures, learning from the people themselves.

Although we can’t cover Indigenous history and heritage in its entirety in a single post, we would like to highlight some of the materials available through Gale—just a fragment of the vast resources you can bring into your classroom.

A Timeline of Native American Achievements

In her piece “‘We Exist’: How to Learn About Native Americans Through Native Lenses,” Farina King, a citizen of the Navajo Nation and associate professor of Native American studies at the University of Oklahoma, writes:

“The language and terms you use, your visuals, and the overall tone of your lessons matter. Beware of thinking in terms of ‘vanishing’ cultures, romanticizing Native American life past or present, or reveling in the ways Indigenous people have been victimized. Native Americans are strong, resilient peoples who have a future to sustain.”

We have included the following timeline to show the triumphs, accomplishments, and important historical moments for Indigenous peoples from a broad range of traditions across the Americas. We’ve also included resources from Gale In Context: High School to help shape your lesson plans for this November.

c. 1200–400 BCE: Ancestors of the Aztec and Maya people in modern-day Mexico domesticate corn, beans, and squash, setting in motion an agricultural revolution that fuels the rise of the Olmec civilization (c. 1200 BCE). Their innovations in astronomy and language lay the groundwork for later Mesoamerican cultures like the Maya and the Aztecs. As these practices spread northward, communities refine their agrarian techniques, leading to developments, like interplanting.

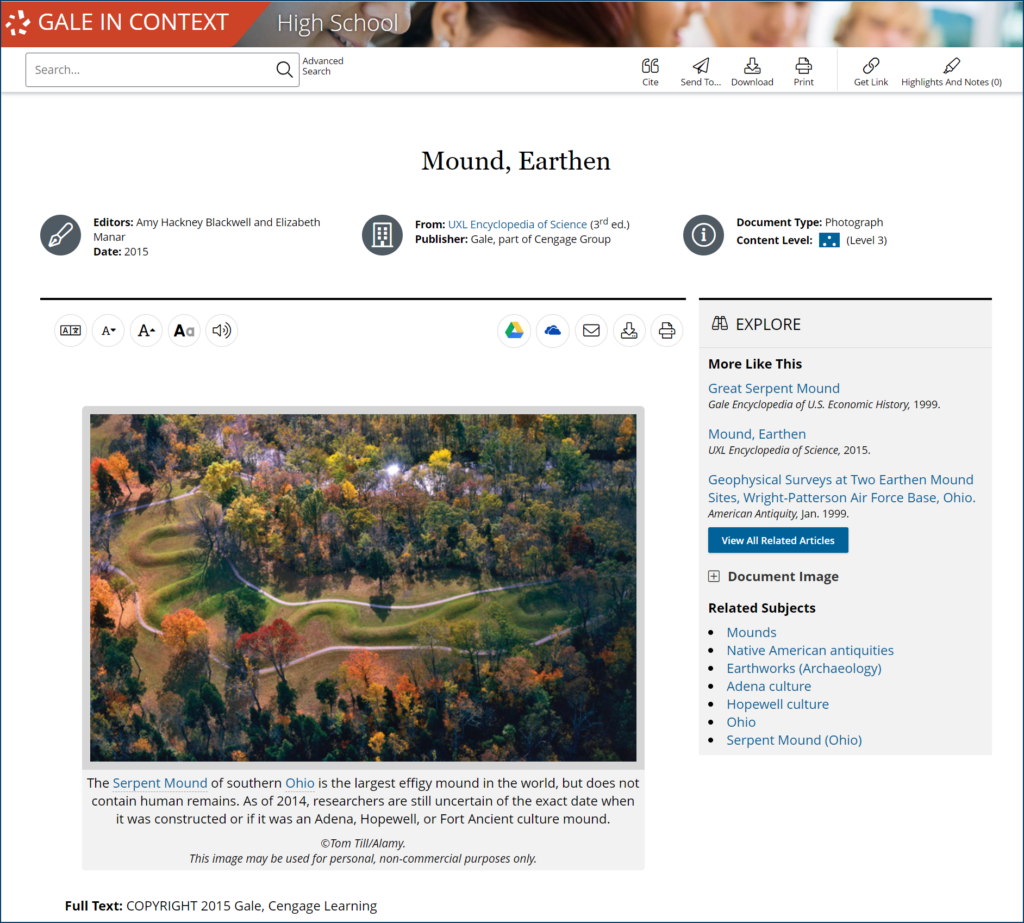

c. 800 BCE–500 CE: The Poverty Point, Adena, Hopewell, and Mississippian cultures of the Ohio River Valley create elaborate earthworks and ceremonial mounds, representative of the sophisticated burial traditions of cultures from the early Woodland period.

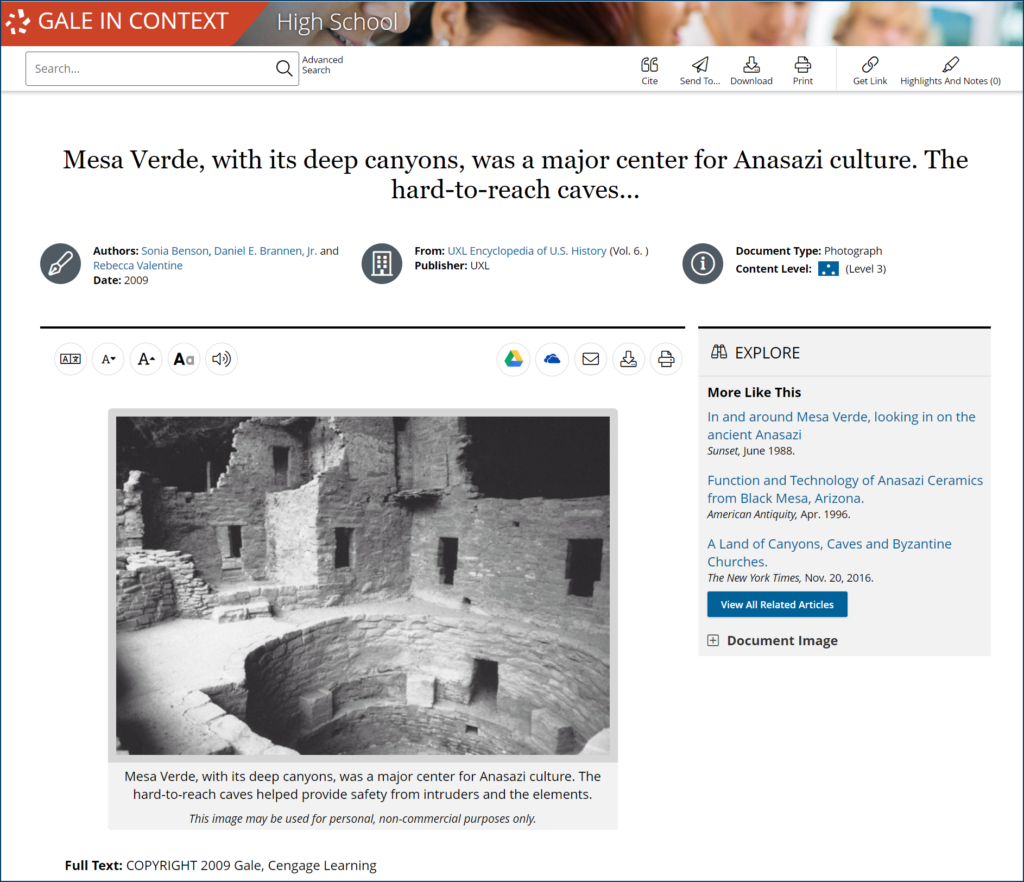

c. 100 BCE–1500 CE: In the challenging environment of the American Southwest, the Ancestral Pueblo, or Anasazi, demonstrate their impressive engineering abilities. Along with cliff dwellings that still stand at sites like Mesa Verde, they also leave evidence of environmental adaptations like dry farming and irrigation.

c. 1600 CE: Hiawatha leads the establishment of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy, previously called the “Iroquois Confederacy,” though Iroquois is an outdated term that many consider to be offensive. Before the confederacy, the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, and Seneca nations were in constant conflict. However, they recognized that continuous warfare weakened their communities and left them vulnerable to external threats. Hiawatha’s efforts in creating the League of Five Nations are recognized as one of the earliest and most sophisticated forms of democratic governance in North America, and it even influenced aspects of the U.S. Constitution.

1500s: Horses arrive with Spanish explorers. Plains nations like the Sioux and Comanche quickly develop strong riding cultures, making hunting more efficient and expanding their influence across the Great Plains.

1621: After the Pilgrims land at Plymouth Rock, Samoset, an Abenaki leader, paves the way for cordial relations between the newly arrived English and the Wampanoag people. Later that year, Chief Massasoit’s assistance in helping the Pilgrims with crop cultivation leads to the first Thanksgiving feast. This tenuous and short-lived cooperation demonstrates the Wampanoag’s mastery of local resources.

1675–78: Under King Philip or Metacom, a coalition of Native tribes, including the Wampanoag, Nipmuc, Pocumtuc, and Narragansett, engage in battle against English settlers encroaching on Indigenous territories in southern New England. Although King Philip’s War ultimately ends in defeat, it was a powerful demonstration of the tribes’ willingness to fight for their sovereignty.

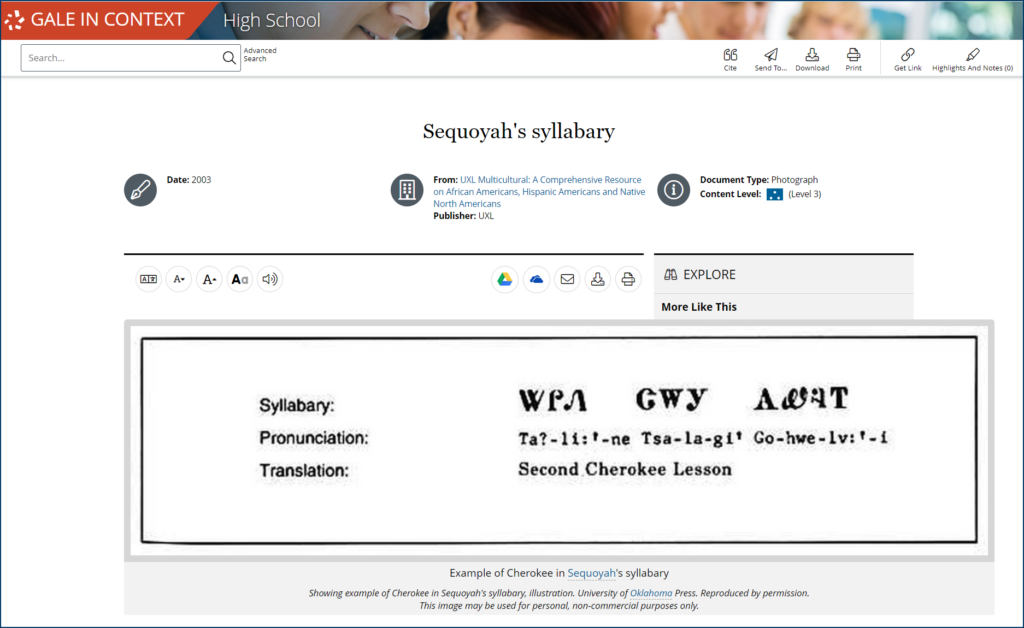

1821: Sequoyah finalizes the Cherokee syllabary, which brings widespread literacy to the Cherokee people.

1834: Mahaska, or White Cloud, a leader of the Ioway nation, travels to Washington, D.C., to advocate for his tribe’s land rights. During this diplomatic effort, he meets with government officials, including President Andrew Jackson, to negotiate the terms of treaties and secure protections for his people.

1868: Barboncito secures the Treaty of Bosque Redondo, which allows the Navajo people to return to their ancestral lands.

1879: Ponca chief Standing Bear makes history when a U.S. court recognizes Native Americans as “persons” under the law, affirming the right to habeas corpus and that “Native Americans . . . possessed an inherent right of expatriation—that is, a right to move from one area to another as they wished.”

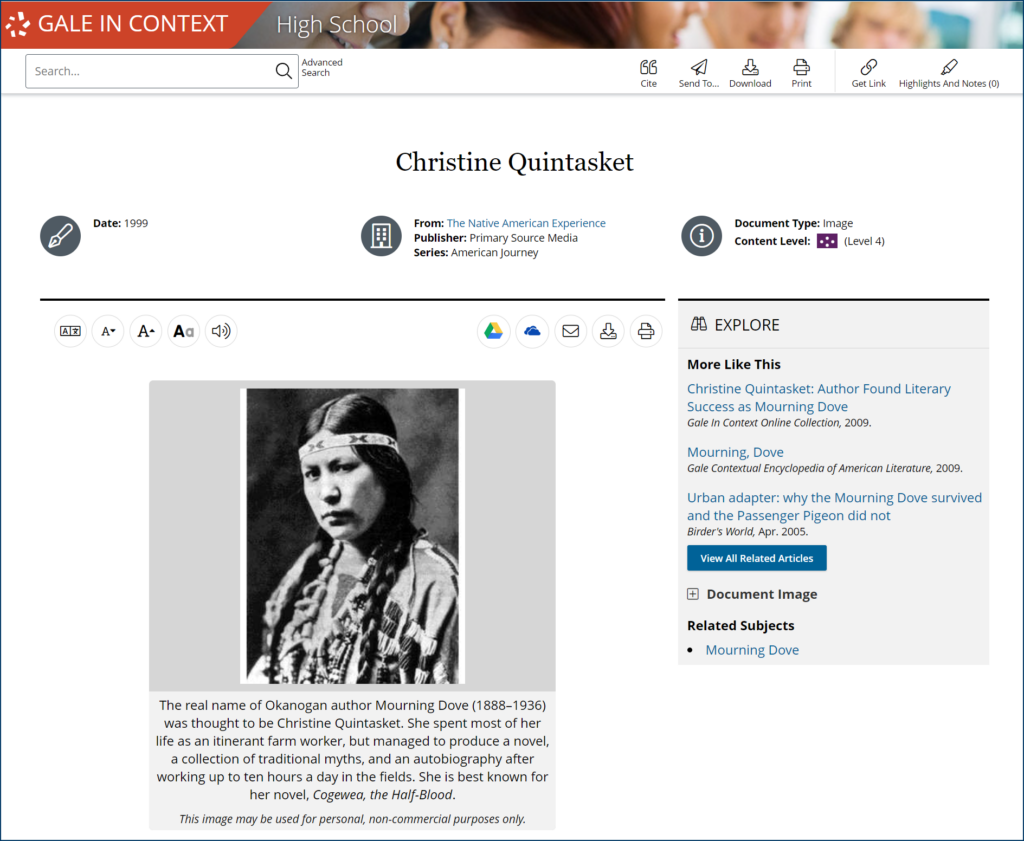

1888: With the publication of Cogewea, the Half-Blood, Mourning Dove becomes the first Native American woman to publish a novel.

1913: Susan La Flesche Picotte, the first Native American woman to earn a medical degree in the United States, breaks barriers in the medical field by opening a hospital on the Omaha Reservation.

1968: Native American activists Russel Means, Clyde Bellecourt, and Dennis Banks found the American Indian Movement (AIM) in Minneapolis, Minnesota. They come together to create a grassroots organization focused on addressing the system of poverty, police brutality, and racism faced by urban Indigenous communities. AIM still exists today, pushing for legal and social changes that protect Native American religious freedom and the return of sacred sites.

1969: N. Scott Momaday’s novel House Made of Dawn earns him the Pulitzer Prize, making him the first Native American to receive this honor and bringing Indigenous literature into the mainstream.

1973: Ada E. Deer leads the successful fight to restore federal recognition to the Menominee Tribe, reversing the termination policy that had stripped them of their rights. Her leadership in the Menominee Restoration Act of 1973 was a major victory for Native sovereignty and set a precedent for other tribes facing similar challenges. She later goes on to become the first woman to head the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs in 1993.

1990: The Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act gives tribes control and ownership over “Native American cultural objects and human remains found on federal and tribal lands” and requires museums or institutions receiving federal funds to repatriate sacred objects to their tribal communities.

2002: John Herrington of the Chickasaw nation becomes the first Native American in space when he flies aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour.

2016: The Standing Rock Sioux Tribe leads protests against the construction of the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL), which threatens the community’s water supply. These protests spark a wave of Indigenous activism for tribal sovereignty and environmental justice, bringing together around 200 tribes that hadn’t been united for more than a century.

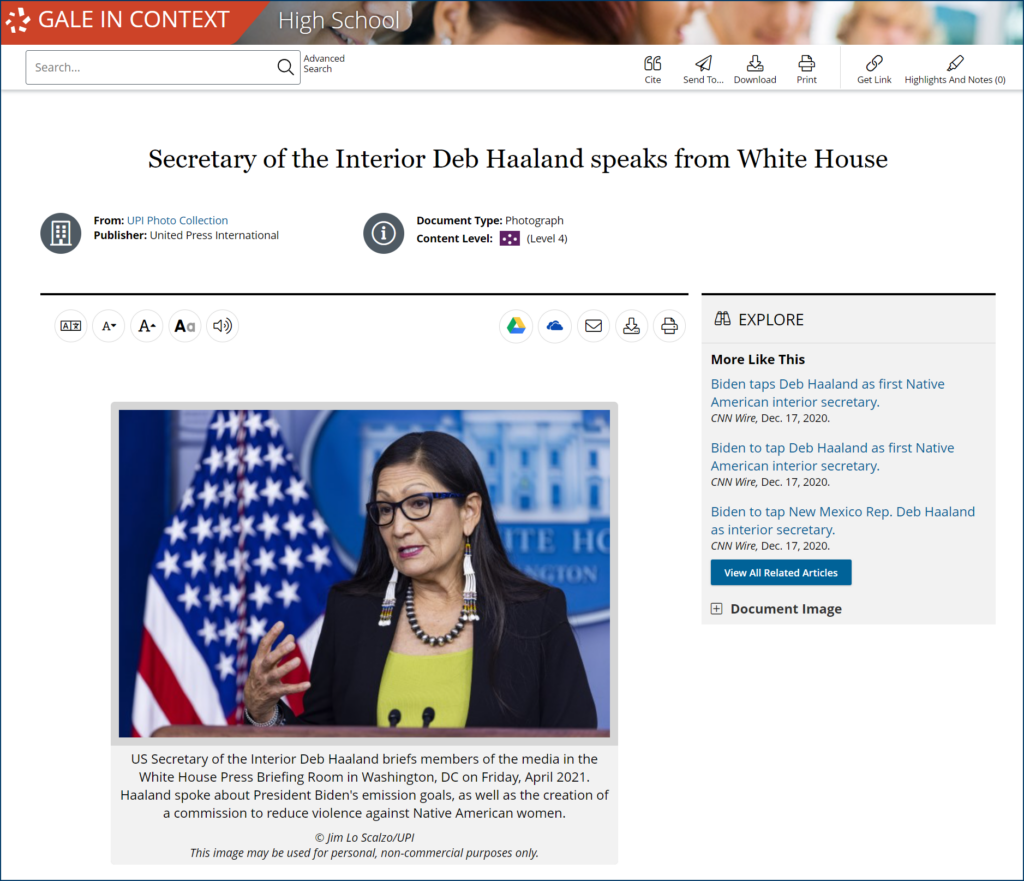

2018: Deb Haaland, a member of the Laguna Pueblo, makes history as one of the first Native American women elected to Congress along with Sharice Davids. Haaland’s commitment to Indigenous rights and environmental issues leads to her appointment as Secretary of the Interior in 2021, making her the first Native American to hold a U.S. Cabinet position.

2020: The Klamath Tribes successfully catalyze the removal of dams along southern Oregon and northern California’s Klamath River, restoring salmon runs sacred to the nation’s cultural fishing practices.

2021: The First Americans Museum in Oklahoma opens to preserve and celebrate the diverse histories and cultures of Native American nations. Ginny Underwood, the museum’s marketing communications manager, shares, “It’s healing in some capacity because we’ve not ever had something like this for our communities. And it’s also a bridge-building opportunity for us to share our cultures and traditions with others.”

Shifting Perspectives About Native American Heritage and History

Educators have an important role in rejecting outdated narratives, painting Indigenous peoples solely as victims of history. Instead, we can pass on stories of their ingenuity and enduring contributions by elevating the voices of those changemakers. This perspective honors the past while encouraging students to recognize Native communities as active and thriving.

If you’re interested in resources that capture the depth and diversity of Native American experiences, please reach out for a free trial to explore Gale In Context: High School’s collection of materials that invite your students to engage meaningfully with Indigenous cultures.