Each year, Earth Day—observed on April 22—reminds us of the power of collective action, like planting trees, reducing waste, and making sustainable choices. These efforts matter, but they are only part of a much larger story.

Across the globe, scientists and conservationists are tackling environmental challenges on a massive scale, proving that ecosystems can recover when people step in to protect and restore them.

This April, introduce young learners to the challenges ecosystems face, the people working to ensure their survival, and the science of restoration with the Earth Day topic page within Gale In Context: Elementary. With this learning tool, K-5 students can find trusted, curriculum-aligned content—including reference pages, periodicals, photos, and videos—in an intuitive, kid-friendly platform.

Coral Reefs

Coral reefs support some of the most diverse ecosystems on Earth. Despite covering only around 1% of the ocean floor, reefs support nearly 25% of all marine life.

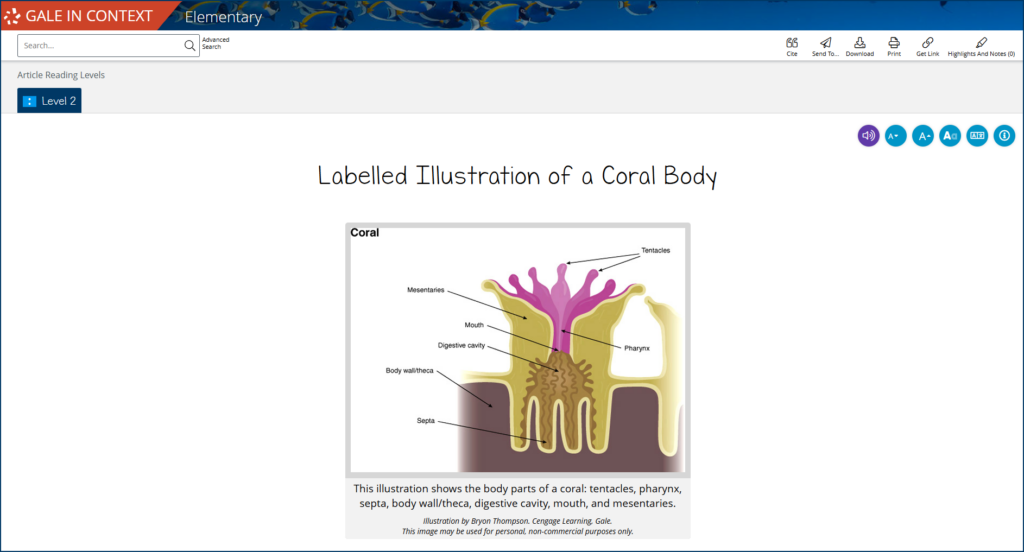

At first glance, reefs may look like colorful rock formations, but they are built over thousands of years by tiny marine creatures called coral polyps. As generations of these polyps die, they leave behind their hard limestone exoskeletons, gradually forming the massive structures that sustain marine ecosystems.

The top layer of coral, however, remains very much alive. Corals survive through a delicate partnership with microscopic algae called zooxanthellae. These algae provide corals with nutrients and oxygen through photosynthesis, giving reefs their vibrant colors. In return, corals provide the algae protection and the compounds they need to grow.

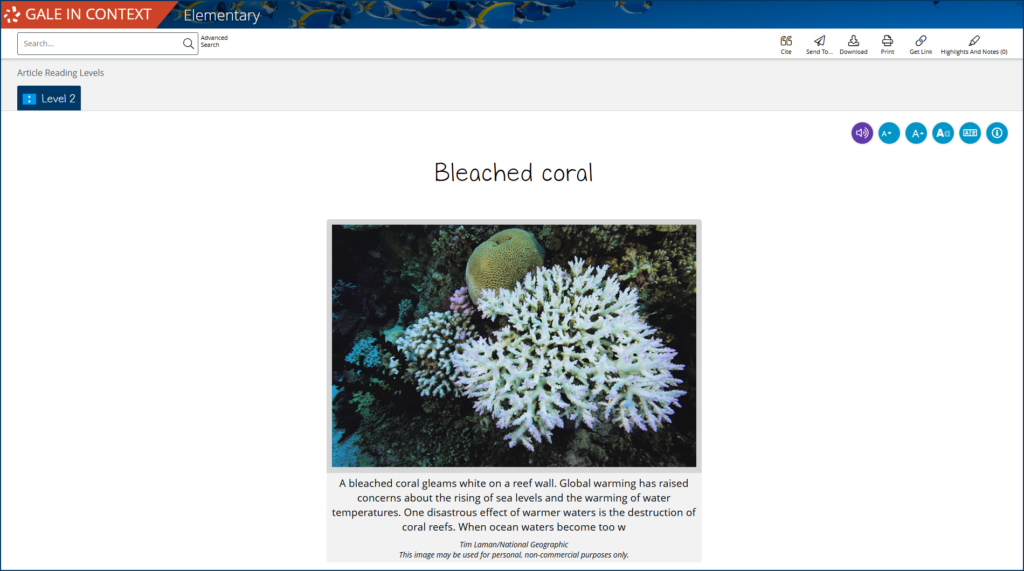

The Problem: Coral Bleaching

As ocean temperatures rise, this fragile balance is breaking down. When waters become too warm, corals expel the algae that sustain them, a process known as coral bleaching. Corals lose their color, starve, and struggle to survive without their algae partners. If water temperatures return to normal, reefs can sometimes recover—but if not, the coral may die.

Mass bleaching events have become increasingly common, with large sections of the Great Barrier Reef experiencing severe die-offs five times since 2016. Scientists warn that if warming trends continue, coral reefs may decline drastically within the next few decades.

Success Story: Planted Polyps Begin the Reproduction Process

Scientists at Mote Marine Laboratory in Florida are working to restore the reefs by breeding corals that are naturally resistant to disease and heat stress. They’ve planted more than 216,000 coral fragments to help rebuild the reef naturally.

In 2020, two species—mountainous star coral (Orbicella faveolata) and staghorn coral (Acropora cervicornis)—began reproducing independently, a first for restored corals in Caribbean waters. Researchers are now studying whether these corals can pass on the traits that make them more resilient.

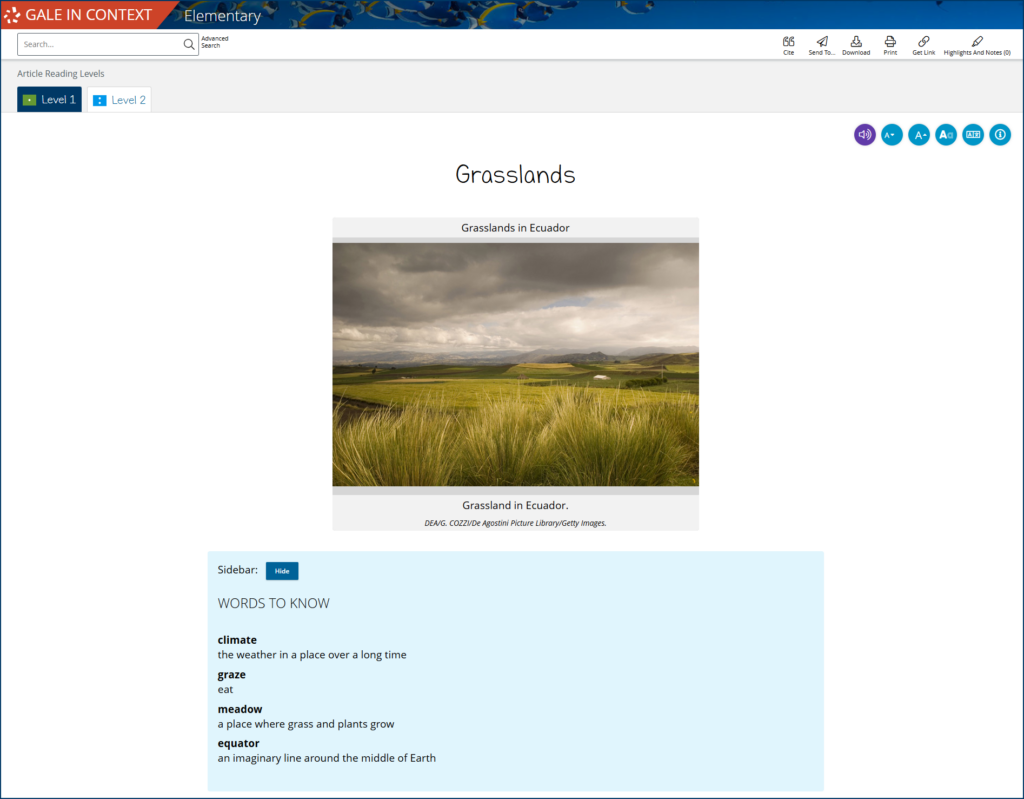

Grasslands

Grasslands span continents, covering nearly a quarter of Earth’s land, from the pampas of South America to the savannas of Africa and the rolling prairies of North America. Unlike forests, where dense canopies create stable, shaded environments, these vast open landscapes are constantly in motion. Winds sweep across the plains, scattering seeds and shaping the terrain. Seasonal fires race through, burning away dead vegetation and clearing the way for new life. Migrating herds graze the land, their hooves churning the soil, pressing seeds into the earth.

Beneath the surface, deep-rooted plants form an intricate network, locking in moisture, preventing erosion, and sustaining the land through drought and seasonal shifts.

The Problem: Disappearing Grasses

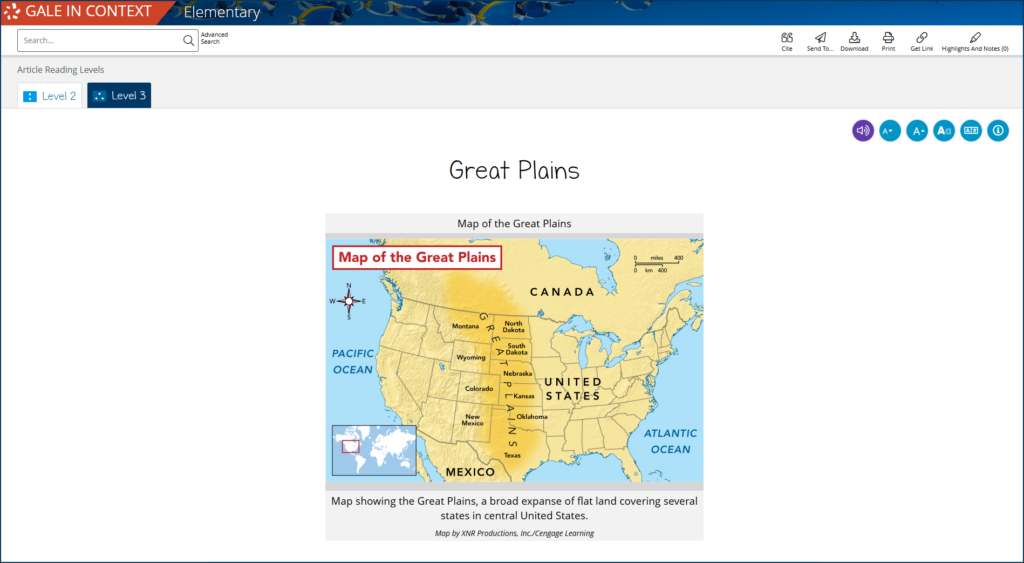

For thousands of years, bison—which we often call buffalo—shaped North America’s grasslands, known as the Great Plains. Moving in vast herds, they grazed selectively, preventing any one plant species from dominating the landscape.

However, by the late 1800s, this balance collapsed. Mass hunting campaigns, fueled by commercial greed and the mistaken belief that the American West held limitless resources, drove bison to the brink of extinction. Once numbering between 24 and 60 million, their population plummeted to fewer than a thousand in just a few decades.

The loss of these keystone grazers set off a chain reaction, affecting everything from soil health to the survival of prairie species like black-footed ferrets, burrowing owls, and countless insects that depend on native vegetation.

Success Story: Reintroducing the Buffalo to the Prairies

At Wind Cave National Park in South Dakota, conservationists are working to strengthen one of the last genetically pure bison herds in North America. Unlike many modern bison, which have been crossbred with cattle, the Wind Cave herd descends from a population untouched by hybridization.

To protect this rare genetic lineage while still aiding in prairie conservation, scientists and the InterTribal Buffalo Council—a coalition of more than 80 Native American tribes—are working to return bison to tribal lands. These efforts restore the prairie and reconnect Great Plains Indigenous communities with a species central to their culture.

Wetlands and Marshes

Wetlands, also known as swamps or marshes, are waterlogged landscapes that act as nature’s filtration system, absorbing pollutants and trapping sediments before they can enter rivers, lakes, and oceans. They do this because of their dense vegetation and slow-moving waters, which allow sediment to settle and harmful substances to break down naturally.

In addition to keeping waterways clean, wetlands adjust to seasonal changes to support the life within them. During heavy rains, they soak up excess water like a sponge, reducing flood risks; in dry periods, they gradually release stored moisture, keeping surrounding habitats hydrated.

Because of this, they sustain an astonishing variety of species. Migratory birds return when waters are at their highest, drawn by the abundance of fish. Amphibians, like frogs and salamanders, rely on shallow pools for breeding, while larger mammals, such as moose and beavers, depend on wetland vegetation for food and shelter.

The Problem: The Earth’s Natural Filters Are Under Threat

Since the 1780s, the continental United States has lost more than 50% of its wetland habitat, with millions of acres drained or destroyed for agriculture, urban expansion, and industrial development. Without these natural sponges to absorb excess rainwater, low-lying regions face more frequent and severe flooding, while pollutants flow unchecked into rivers and oceans, degrading water quality.

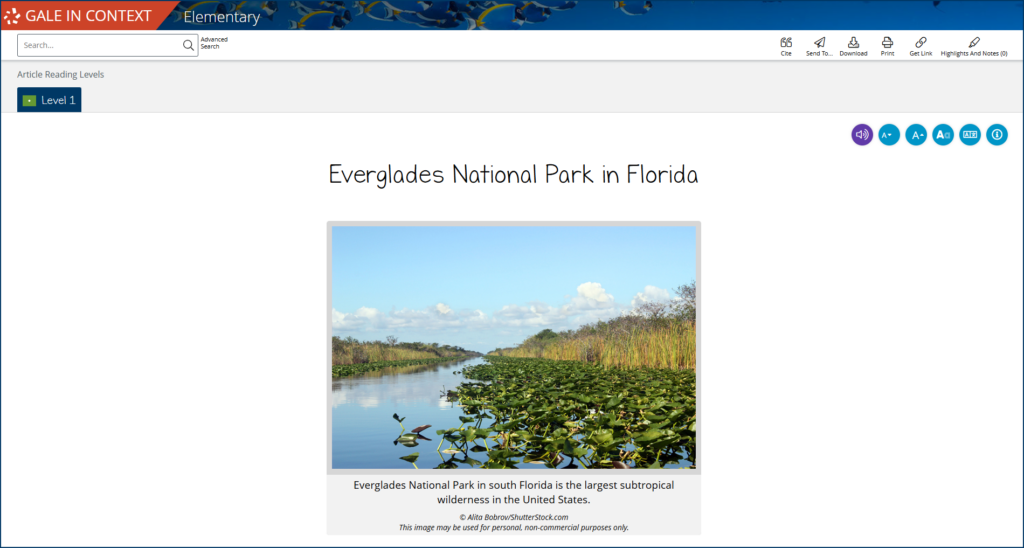

Two of the most dramatically affected areas are the Mississippi River Basin and the Florida Everglades.

As Mississippi River Basin wetlands have disappeared, runoff from farms and urban centers surges downstream, fueling a hypoxic “dead zone.” Because they lack oxygen, these waters can no longer support marine life, devastating local fisheries and disrupting coastal food webs.

Meanwhile, human-engineered canals and levees have rerouted natural water flow in the Everglades, drying out some regions while unpredictably flooding others. This disruption has weakened one of North America’s most diverse wetland ecosystems, threatening species like the Florida panther and wood stork.

Success Story: Bringing Fresh Water to the Florida Everglades

The National Parks Conservation Association is collaborating with the Army Corps of Engineers to construct a reservoir system designed to restore 78 billion gallons of fresh water to the Everglades annually. By mimicking the region’s original water cycle, this initiative aims to rehydrate drained wetlands and restore habitats to support local biodiversity.

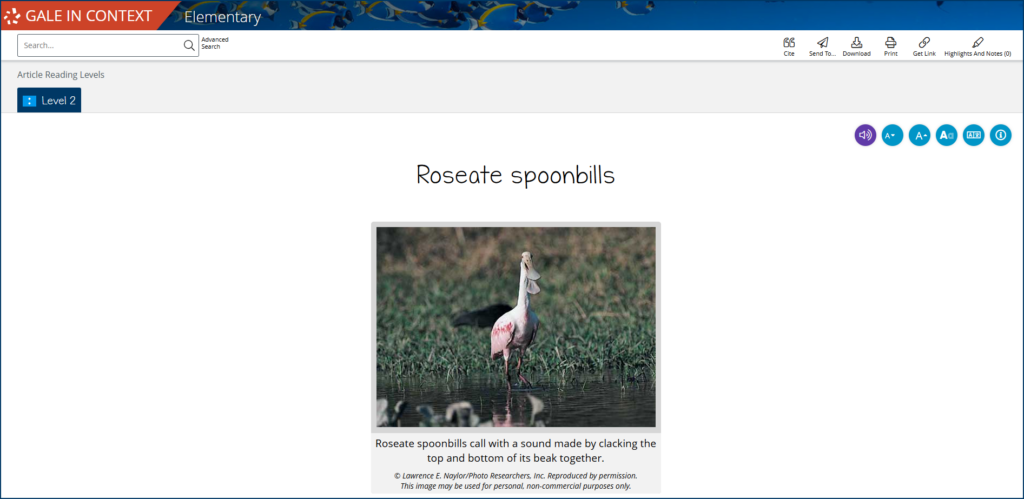

Early signs of recovery have seen wading bird populations, including egrets and spoonbills, rebounding as their feeding grounds regain stability and native plant species reclaiming areas once overtaken by invasive vegetation.

Across North America, scientists, conservationists, and local communities are proving that damaged landscapes aren’t beyond repair. Prairie grasses reclaim soil once lost to erosion, wetlands improve water quality in regions long polluted by runoff, and coral reefs are showing signs of life where bleaching had once stripped them bare.

With Gale In Context: Elementary, you have the resources to share these stories and countless others while inspiring future environmental activists to do their part in keeping our home healthy. Reach out to your Gale sales rep to learn more about what our platform offers your classroom.