| By Beth Manar |

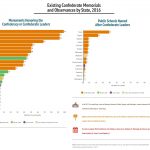

Though the US Civil War officially ended with the surrender of Confederate general Robert E. Lee in 1865, the rift that began when eleven slave-holding Southern states seceded from 1860 to 1861 had repercussions that are still felt more than 150 years later. It is estimated that more than 620,000 soldiers on both sides died in the war. After both the North and South buried and mourned those who fought and died, the survivors placed plaques, erected statues, and named streets and buildings to memorialize them. Some of these memorials were completed in the immediate aftermath of the war. However, decades (and in some cases, more than one-hundred years) later additional memorials to Confederate generals and soldiers were erected in the South in what some saw as responses to rights being gained by African Americans during reconstruction in the South and again during the Civil Rights era. According to estimates by the Southern Poverty Law Center, as of 2016, there were hundreds of statues and monuments on public or government property, as well as schools, US military bases, and counties and cities named for Confederate politicians and military figures, mostly in states that were a part of the Confederacy (though there are exceptions). Statistics on where these are located are shown in the graphic below:

Though many of these have stood for decades, in recent years controversy has begun to surround such memorials, as well as the use of the Confederate flag on state government property and holidays in some Southern states that honor Confederate soldiers and generals. Many see these merely as historical symbols and take pride in their Southern heritage and ancestors. However, others see them as representations of the failed, and treasonous, actions taken by those who wanted to continue slavery and as a continuing insult to the descendants of those who were enslaved. In extreme cases, such symbols have been used in ways that have been associated with overt racism and violence.

In one such case, in 2015 white supremacist Dylann Roof murdered nine black parishioners at a prayer service in a Charleston, South Carolina, church. Materials found in his home and on his computer showed images of him posing with Confederate flags and memorabilia, a Ku Klux Klan hood, and racist text that referred to the Confederacy and Nazi symbols. The legislature in South Carolina decided to remove the Confederate flag from the state capital later that year, and other cities and states began discussions about moving such symbols to museums and other nongovernment venues.

These proposed changes provoked controversy, both among those who believe the symbols should remain because of their historical significance but also with so-called “alt-right” extremists. Two years later, on August 12, 2017, a group of white nationalists, white supremacists, neo-Nazis, and Ku Klux Klan (KKK) members gathered in what they called a “Unite the Right” rally to protest the removal of a Confederate memorial at Emancipation Park in Charlottesville, Virginia, and the discussion of removing others like it around the nation. The symbols and chants of the “alt-right” included KKK, Confederate, and Nazi-themed slogans and emblems. Some of those rallying were members of militias and were heavily armed with everything from bulletproof vests to semi-automatic weapons. Counter-protesters clashed with the “alt-right” demonstrators, and an alleged white nationalist with neo-Nazi ties plowed a car into a crowd of those protesting the hate groups, killing a 32-year-old paralegal, Heather Heyer, and injuring nineteen others. Two state troopers were also killed when their helicopter, which had been monitoring the rally, crashed. The violence once again sparked heated discussions about what Confederate symbols mean to different Americans given the troubled legacy of race relations in the United States, as well as issues of racism, civil rights, freedom of speech, the right to bear arms, militias, and the political and social divisions within the United States.

To get more context about some of these current, controversial, and sometimes divisive issues, see Gale’s Opposing Viewpoints In Context, which now includes additional commentary (a brief summary and questions to consider) on opinion articles with a wide variety of perspectives in the Featured Viewpoints category when accessed through the topic page:

To get further background on the history of slavery, the Civil War, Reconstruction, the Civil Rights movement, and more, you can also go to U.S. History In Context, where you will discover in-depth coverage on these topics:

Not a subscriber to Gale’s In Context suite? Request a trial today!

Banner Image Citation: “A Statue of Confederate General Robert E. Lee.” Gale Opposing Viewpoints in Context, Gale, 2017. Opposing Viewpoints in Context, link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/RODQAU797956955/OVIC?u=pangea&xid=20b5a534. Accessed 5 Sept. 2017.