| By Gale Staff |

Once reserved for Santa Claus and starry-eyed explorers, the North Pole has become an increasingly urgent matter of political concern. Thawing permafrost and retreating ice have already spurred conflict regarding newly accessible shipping corridors and untapped energy reserves. As the ice recedes, what was once an isolated region draws the attention of powerful economic and military interests as they position themselves to lay claim to territory.

The pace is quick, and the stakes are rising—often with limited input from the Indigenous communities living in the region.

These tensions are central to the 2025–26 National High School Policy Debate Topic, which asks participants to debate the following assertion: “The United States federal government should significantly increase its exploration and/or development of the Arctic.”

Rather than settling for a superficial take on the issue or turning to Google for talking points, you can depend on the National Debate Topic: Arctic page in Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints. This cross-curricular research database brings together coverage of current events with in-depth context on the scientific, political, and historical forces shaping the region. Together, these resources challenge students to think critically and engage the topic from multiple angles in order to build well-reasoned perspectives.

Competing Interests in the North

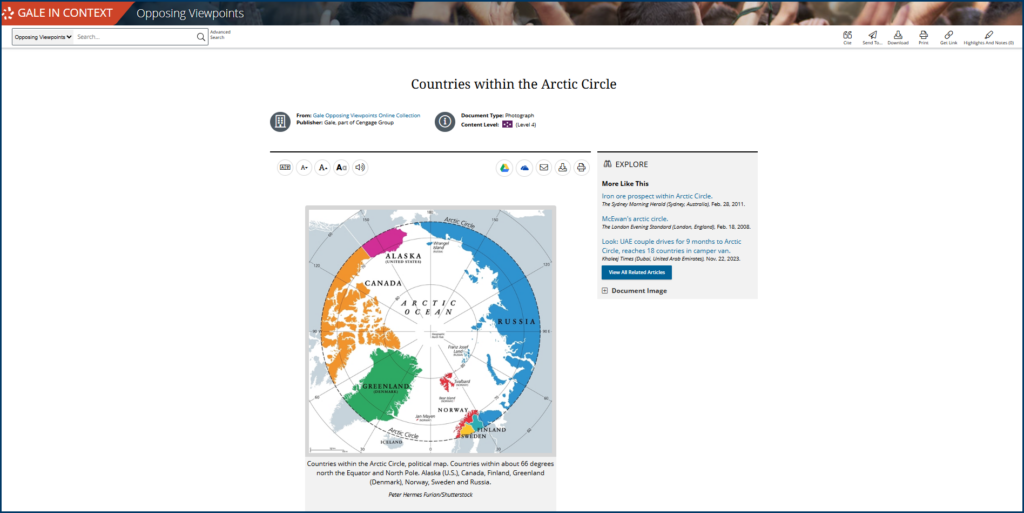

As the Arctic becomes more accessible, nations are moving to reinforce, and in some cases expand, their territorial claims. Some follow formal legal channels, primarily the U.N. Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS). Others rely on physical presence or strategic partnerships to secure influence.

Legal Claims

Under international law, countries with ocean-facing borders are granted a 200-nautical-mile Exclusive Economic Zone, giving them special rights to the marine resources—both living and non-living—within that boundary. However, under UNCLOS, nations can submit scientific evidence to extend these rights.

One example is that of the Lomonosov Ridge, a subsea mountain range spanning the Arctic Basin, which is central to many of these claims. Russia contends the ridge is geologically connected to its Siberian continental shelf, while Denmark argues that it connects to Greenland. Canada has made similar claims about Ellesmere Island.

These overlapping claims between countries within the Arctic Circle will take years to resolve, and, in the meantime, presence on the ground or at sea matters more than paperwork.

Militaristic Power

With no binding rules restricting military infrastructure in the Arctic, nations have leveraged a low-risk way to assert control by building assets like research stations and bases. This passive form of militarized engagement is less formal than a territorial claim but visible enough to signal long-term intent without triggering direct conflict.

Russia has secured access to maritime shipping lanes by restoring and expanding its military bases and logistics hubs across the New Siberian Islands, Franz Josef Land, and the Kola Peninsula to support operations along the Northern Sea Route.

The United States, which declined to ratify UNCLOS, has responded in kind, reopening Arctic training programs and publicly identifying the region as a national security priority. That said, the U.S. is preparing to provide additional evidence for its claim to surrounding shelf regions off the coast of Alaska by conducting hydrographic surveys of the Chukchi Plateau and the Beaufort Sea.

Strategic Presence

When China declared itself a “near-Arctic state,” the country signaled its intention to participate in Arctic development and policymaking, even without territorial claims of its own. Its strategy runs through infrastructure—built along Russia’s Northern Sea Route—and through partnerships that secure access without formal authority.

China’s fleet of icebreaker vessels, Xue Long, Xue Long 2, and Zhong Shan Da Xue Ji Di, has sailed Arctic waters on multiple expeditions, testing their navigational readiness for sustained operations along the region’s increasingly viable trade corridors. They’ve also undertaken joint ventures with Russian companies to finance massive liquefied natural gas projects on the Yamal Peninsula, securing export routes along the Northern Sea Route and improving access to European markets.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What are the limitations of relying on legal frameworks like UNCLOS when multiple countries claim the same territory?

- Do you think that China’s involvement in the Arctic is a legitimate form of global cooperation, or an attempt to gain influence in a region where it holds no territory?

- How does militarized infrastructure function as a tool of influence in the Arctic? At what point does that development cross the line into hostile action?

Whose Arctic Is It? Indigenous Sovereignty

International conversations about Arctic development usually focus on the power of countries, circumventing the rights of the Indigenous peoples who have lived in and cared for this region for thousands of years. These communities governed Arctic territories long before national borders existed and have deep cultural ties to the land and sea. Nevertheless, their authority is continuously sidelined in favor of state interests, even when protections exist on paper.

Inuit

Until 1999, Nunavut was part of Canada’s Northwest Territories, at which point it became the country’s newest and largest territory. Although it covers nearly a fifth of the country’s total landmass, this region the size of Western Europe has a population of just under 30,000 people, most of whom are Inuit. Nunavut’s government gives Inuit people a stronger role in local decision-making. However, that authority’s power is limited to legislating on internal matters, while issues like natural resource usage remain with the federal government.

Sámi

The Sámi live across northern Scandinavia and into Russia , where they’ve looked after communal reindeer herding grounds for thousands of years. In Norway, the government approved wind energy projects directly on these lands, fragmenting migration routes that serve as the backbone of their economy and hold deep meaning their culture’s seasonal movements.

The Sámi herders brought their case before the courts, where judges ultimately ruled in their favor, stating that the wind farms infringed on rights protected by Article 27 of the United Nations’ International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. Even with this decision, the turbines have continued to operate. In protest, Sámi activists returned to Oslo in January 2024, where authorities arrested 20 individuals for obstructing entry to several government buildings.

Chukchi

The Chukchi of northeastern Siberia occupy some of Russia’s most resource-rich Arctic territory and depend on a subsistence lifestyle based around a healthy tundra ecosystem that can support reindeer herding, coastal fishing, and seasonal hunting. To preserve these lands, Article 69 of the Russian Constitution classifies Chukchi as “small-numbered Indigenous people,” a status that, in theory, guarantees certain rights and protections.

However, these protections did nothing to stop mining operations from violating permit agreements. In 2007, drilling and fuel spills caused extensive environmental damage in Chukchi territory. The impact only grew in 2011, when a subcontractor hauled cargo across the river floodplains in the middle of salmon spawning season and inflicted lasting harm on a fragile ecosystem critical to Chukchi food sources. When Chukchi leaders protested the destruction, regional authorities revoked the community’s territorial rights instead of holding the company accountable.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Do you think Indigenous communities should have full authority over natural resource development on their traditional lands even when those lands fall within a modern nation-state? Why or why not?

- What strategies could governments use to balance economic development with the obligation to protect ecosystems that are central to Indigenous survival and self-determination?

- What would it take for Indigenous land rights to be enforced as seriously as national interests or corporate contracts? What enforcement mechanisms would be implicated?

Global Cooperation Models for Comparison

There’s a tendency to treat the Arctic as a place where conflict is bound to happen, but that view ignores the fact that countries have managed to work together in other hotly contested areas. Long-term cooperation has taken precedence over competition in two places that are even more remote than the Arctic.

The Antarctic Treaty

At the height of Cold War tensions, competing powers signed the Antarctic Treaty in 1959, establishing the region south of 60°S latitude as a zone reserved for peaceful activity and scientific research. It prohibited military activity—including weapons testing and fortification—and froze territorial claims on Antarctic lands.

Even without a central enforcement mechanism, the Antarctic Treaty has remained intact for more than 60 years.

The International Space Station

After decades of rivalry between spacefaring nations, five space agencies—NASA (United States), Roscosmos (Russia), ESA (Europe), JAXA (Japan), and CSA (Canada)—agreed to a series of intergovernmental agreements signed in the 1990s that resulted in the construction of the International Space Station.

This collaborative project is built so that disengagement would compromise scientific operations and infrastructure on all sides, as technical systems, research schedules, and staffing are interdependent and supported across agencies. Even during periods of political tension, cooperation in orbit must continue because no single partner can keep the system running alone.

Critical Thinking Questions

- What makes international cooperation succeed in some contested regions but not others?

- Unlike the Antarctic or outer space, the Arctic is already bordered by powerful nations with economic and strategic interests. How might that influence the kinds of agreements countries are willing to make?

Debating the Potential Outcomes of Arctic Conflicts

Few parts of the world remain undefined by political boundaries. In the Arctic, where ice once acted as a natural barrier to development, that last layer of protection is melting away. What’s left behind is a legal and ethical vacuum, where competing interests move quickly. This comes at the expense of the Indigenous people, wildlife, and natural resources that have sustained life in the region for centuries.

This year’s debate topic challenges students to examine how the Arctic power vacuum is being filled—whether through legal frameworks, military posturing, strategic partnerships, or boots-on-the-ground research. Debaters will have to question whose authority is being asserted, whose voices are ignored or excluded, and what kind of future we can look forward to in the absence of a consensus.

Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints presents debaters with a collection of sources spanning scientific research, legal analysis, and Indigenous perspectives as well as an abundance of policy commentary and multimedia supplements. Every student can feel confident in building strong arguments grounded in credible evidence. To learn more, please reach out to your local Gale sales representative.