| By Gale Staff |

Rosa Parks was born on February 4, 1913, almost 50 years after the abolition of slavery and just over 50 years before the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

As her life unfolded at the crossroads of these defining moments in American history, she made a courageous decision on a Montgomery bus that brought the collective frustration of black Alabamans to the forefront of the national discourse.

To do her story justice, however, K–12 educators need standards-aligned, age-appropriate resources that move beyond surface-level narratives.

The Rosa Parks topic page, available through Gale In Context: U.S. History, is an engaging online resource portal featuring primary sources, images, videos, audio files, and more. It gives educators a robust repertoire of grade-spanning tools to introduce students to Parks’s life and legacy while meeting each learner at their developmental level.

We’ll introduce you to a few highlights from this collection of high-interest content—and how it can support lesson planning, teaching, and student research in your classroom.

For Elementary Classrooms: Rosa’s Bravery

You can introduce Rosa Parks’s most famous act—refusing to give up her seat to a white passenger on a Montgomery bus—to elementary students to teach them about concepts like fairness, courage, and standing up for what’s right, even when there might be consequences.

It’s a deceptively straightforward story that presents a powerful entry point for young learners to connect the idea of equality to a real person who made a difference.

A Simple Act of Bravery

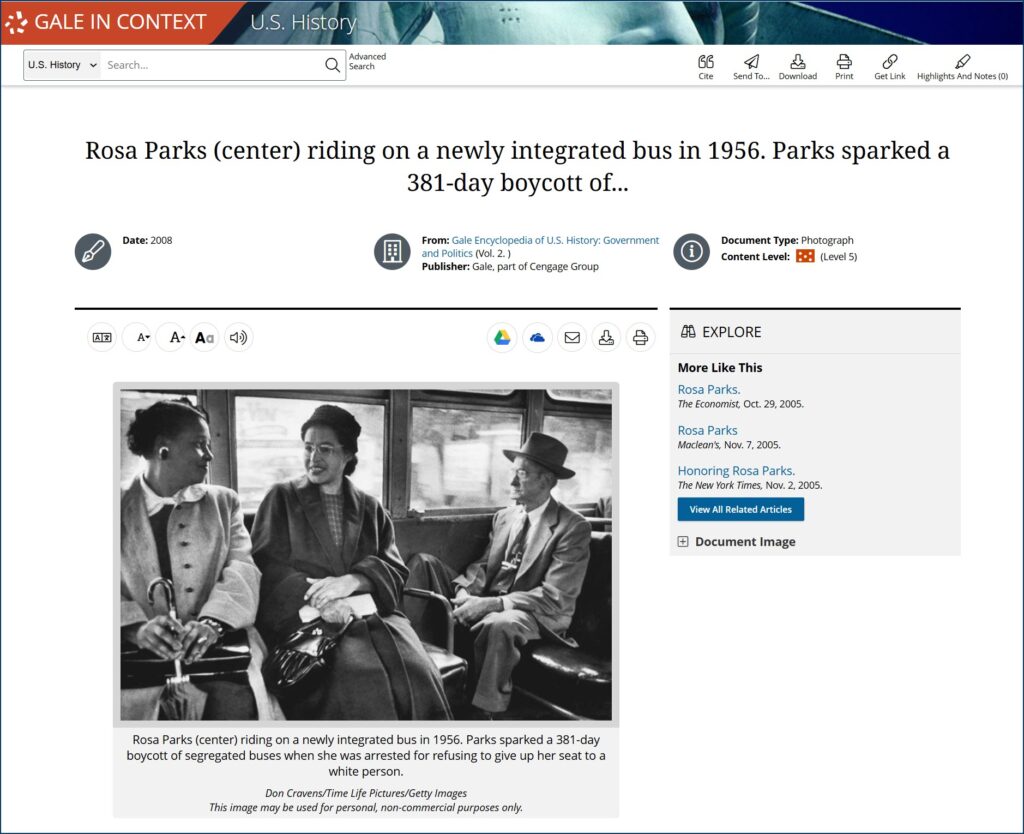

On December 1, 1955, Parks took her place in the first seat of the “colored section” of a Montgomery city bus. As it became crowded, she was ordered to move to accommodate a white passenger. Parks calmly refused, a decision not out of exhaustion, as is often mythologized.

To correct the misconception, she explained, “I was not tired physically or any more tired than usual at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was only forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

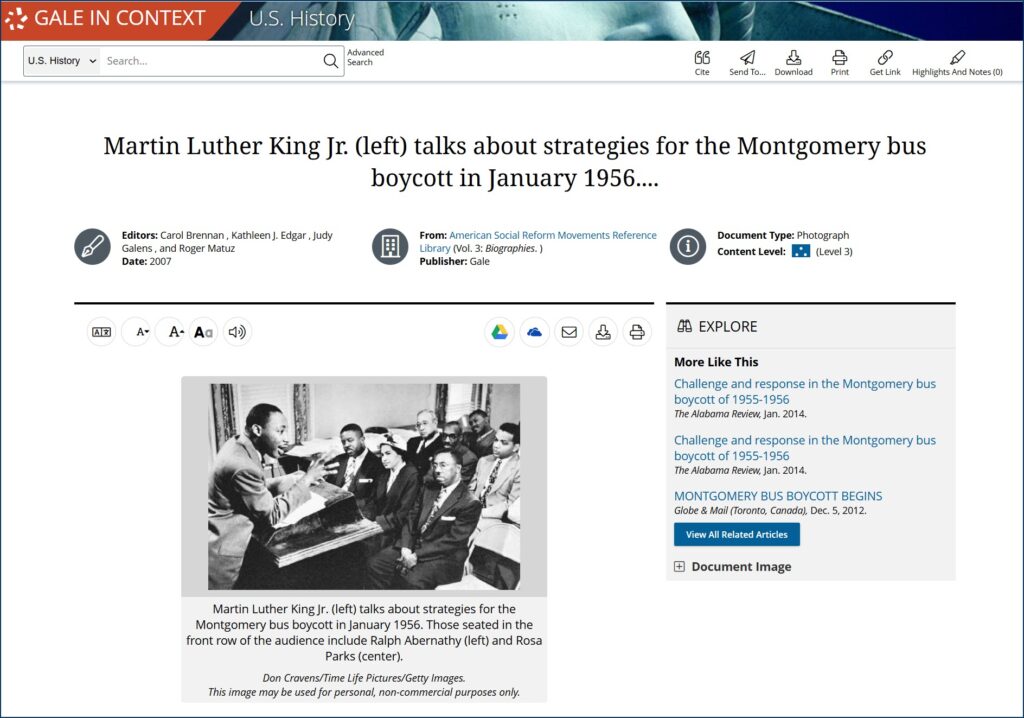

Her arrest sparked a boycott that lasted 381 days. During this time, Montgomery’s black residents—who made up 75% of the city’s bus riders—walked, carpooled, or found other ways to get to work. The economic impact was substantial, costing Montgomery City Lines an estimated $750,000, or $8.8 million adjusted for inflation.

This collective action led to a landmark Supreme Court ruling, Browder v. Gayle, which declared bus segregation unconstitutional in 1956.

Parks’s bravery helps students recognize how important it is to speak out against unfair treatment. One person’s actions, supported by their community, can inspire change for the better.

Discussion Idea: Pair your lesson on Rosa Parks with one of Gale’s eBook biographies for pre-kindergarten through 5th-grade readers. After reading it aloud, prompt your students to think about what they would do if something unfair happened to them. Then, to encourage students to think critically about the importance of empathy, expand the question to include what they could do if they saw something unfair happening to someone else.

For Middle School Classrooms: Systemic Injustices

During the Jim Crow era, laws mandated racial segregation in schools, public transportation, and other areas of daily life. Black citizens faced countless barriers to equality, and those who challenged the norms faced threats of violence and imprisonment for daring to speak up. Providing this historical context emphasizes to students the immense courage it took for Parks to resist injustice.

Combatting Segregation

The “separate but equal doctrine,” dating back to the Supreme Court’s 1896 Plessy v. Ferguson decision, established the legal basis for segregation. However, facilities for black Americans were never equal to those for white Americans.

Parks’s own schooling illustrates just how unequal things were. She attended a wooden, one-room schoolhouse in Pine Level, Alabama, which the community had to build themselves. Students had to cut and haul wood to heat their classrooms, and a single teacher, Rosa’s mother, taught all 60 K–6 students simultaneously.

Meanwhile, white children in the same area attended modern, brick schools funded by taxpayers.

When Parks moved to Montogomery at age 11 to continue schooling, she found things were just as bad in the city. Parks joined the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), where she served as a youth advisor and secretary for the Montgomery chapter. Parks also worked with the Montgomery Voters League to combat voter suppression and supported the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, one of the first black labor unions.

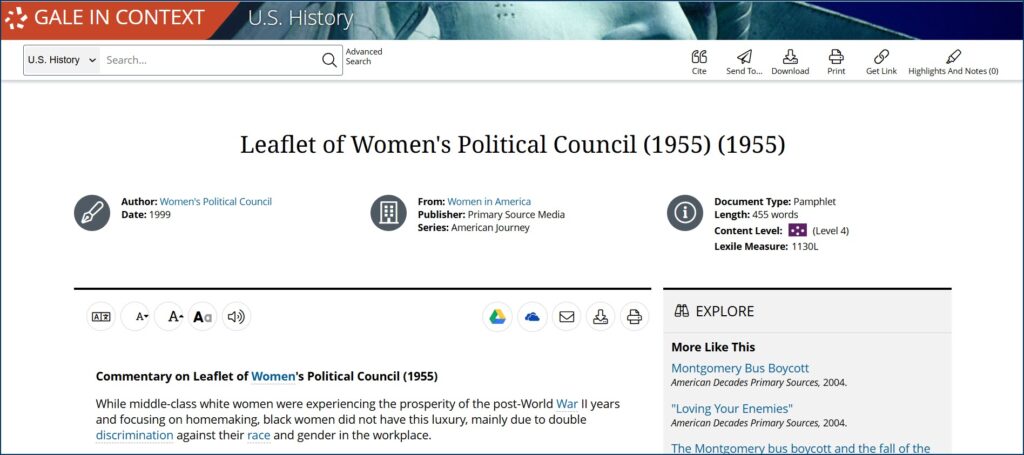

Discussion Idea: Introduce students to primary sources, such as the Women’s Political Council leaflet promoting the bus boycott or the Atlanta Declaration, a 1954 NAACP press conference that championed compliance with court-ordered desegregation in the aftermath of Plessy v. Ferguson. Encourage students to analyze how these documents employed different rhetorical strategies to drive social change. Compare the down-to-earth, community-focused appeals in the leaflet to the elevated, authoritative tone of the Atlanta Declaration. Discuss the importance of knowing one’s audience and how the materials might have resonated.

For High School Classrooms: Rosa’s Later Life

By the time students reach high school, they’re likely familiar with the basics of Parks’s story. However, Parks lived a remarkable life long after December 1, 1955.

Her unwavering commitment to activism provides rich material for exploring Parks’s connection to events like the Detroit Rebellion of 1967 and analyzing how our principles can evolve over time.

Dark Times in Detroit

Despite the victory of Browder v. Gayle, Parks faced lasting repercussions for her participation in the bus boycott. She was fired from her job and blacklisted across the community—ultimately forced to move to Detroit in 1957 due to threats against her safety.

Just as when she moved to Montgomery from the countryside, she found disappointment in a city that failed to live up to its progressive reputation. Life in the North wasn’t much better for black people than it was in the South.

As a child in Alabama, Parks had stood guard with her grandfather, Sylvester Edwards, as Klansmen terrorized their community in the dead of night. Decades later, despite legal advances, violence against black people in Detroit took new forms—often under the guise of law enforcement or through systemic neglect.

In response, Parks pivoted her advocacy efforts toward support for John Conyers’s victorious 1964 congressional campaign. Conyers hired Parks as his secretary in 1965, a position she maintained until retiring in 1988. With her role, Parks became a dedicated advocate for fair housing policies, fighting against redlining and urban renewal projects that displaced black residents under the guise of progress.

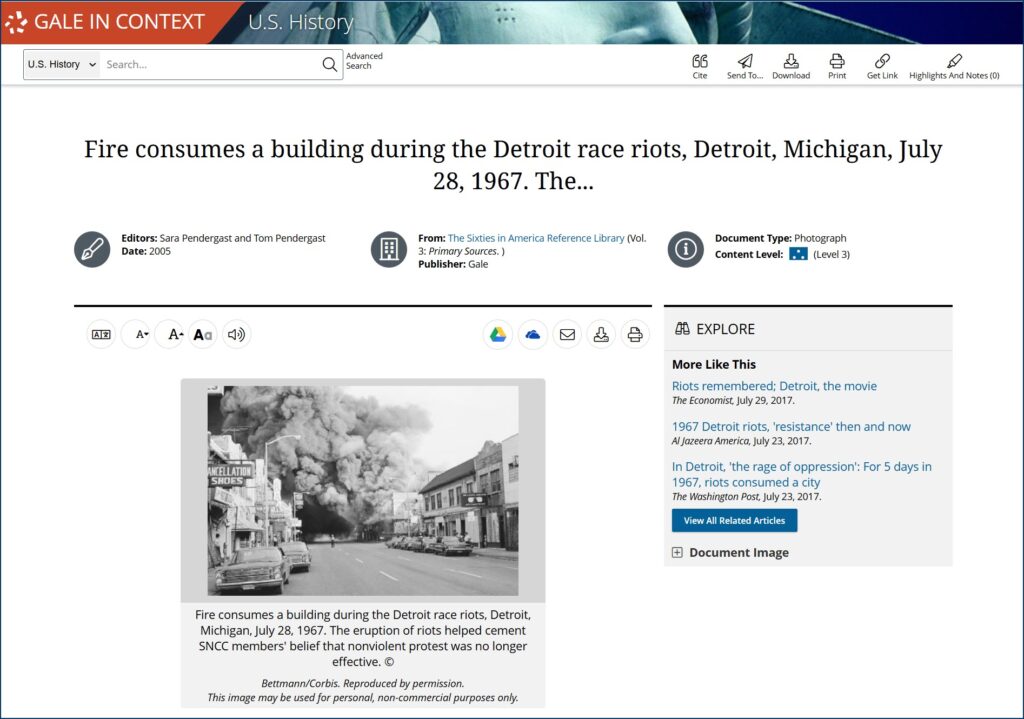

Detroit’s underlying tensions boiled over after police raided an unlicensed bar hosting a welcome home party for two black veterans returning from Vietnam. This raid lit the fuse for the Detroit Rebellion of 1967, a five-day uprising resulting in the deaths of 43 people—33 of whom were black—7,000 arrests, and the burning of more than 1,000 buildings. In the aftermath, Parks, who lived near the epicenter of the destruction, worked with the Virginia Park District Council to improve housing conditions and promote community-driven development.

She also found herself aligning more with Malcolm X’s ideas, particularly his assertion that self-defense and militant action had a place in the fight for equality. While Parks remained a steadfast advocate for nonviolence, she grew sympathetic to his perspective that there were limitations to peaceful protest.

Activity Idea: Using Gale In Context: U.S. History, have students research the Detroit Rebellion, Martin Luther King Jr.’s philosophy of nonviolence, and Malcolm X’s more militant stance. In an essay or debate, ask them to consider the strengths and shortcomings of each approach and tie their analysis to modern struggles for racial and economic justice.

While Rosa Parks’s actions on that Montgomery bus symbolize courage in the face of injustice, her legacy reaches far beyond that single act. She was a lifelong activist, deeply rooted in her community, and dedicated to creating a fairer, more equitable future.

Contact your local Gale sales rep to learn more about Gale In Context: U.S. History and how it can support teaching and learning about this iconic figure across all grade levels.