During LGBTQ Pride Month, we celebrate this community and the impact its members have had on local, national, and international history. Pride is celebrated each June in honor of the Stonewall Uprising, which took place in 1969 in Manhattan. Ever since Pride began as a single-day commemoration in 1970, marches and parades have been part of the event. From their origins as a memorial to their current incarnation as colorful celebrations, pride parades remember the past while serving as acts of resistance against those seeking to strip the LGBTQ community of the rights it has fought so hard to gain.

Inciting Incident

During the 1960s in New York City, a number of repressive laws were in place targeting LGBTQ people. Not only could men be arrested for dressing in drag, but also, acts such as serving liquor to gay people and public displays of homosexuality were outlawed. In this restrictive environment, the Stonewall Inn opened for business on Christopher Street in Manhattan in 1966. The establishment allowed everyone—of any identity or sexual orientation—to be themselves and enjoy the nightlife. The Stonewall Inn became a haven for members of the LGBTQ community, including homeless gay youth.

liquor to gay people and public displays of homosexuality were outlawed. In this restrictive environment, the Stonewall Inn opened for business on Christopher Street in Manhattan in 1966. The establishment allowed everyone—of any identity or sexual orientation—to be themselves and enjoy the nightlife. The Stonewall Inn became a haven for members of the LGBTQ community, including homeless gay youth.

On June 28, 1969, the situation changed forever when the police raided the Stonewall at 1:20 a.m. The bar had been operating without a liquor license because the New York State Liquor Authority would not issue a permit to any business that served gay customers. Though there had been raids on Stonewall before, years of paying off cops had kept the business open—until that June night. With a warrant, the police entered and began arresting patrons who were inside the bar. As those arrested were held outside in handcuffs waiting for squad cars, a crowd gathered and began throwing objects at the police. The situation escalated, with patrons of Stonewall clashing with the police and the crowd setting fire to a barricade put in place by officers who were inside Stonewall.

Though the fire was put out by firefighters and the crowd was dispersed by the police, demonstrations took place for the next six days outside the Stonewall. Over the week, thousands of people showed their support for the Stonewall and the people it served. These events became known as the Stonewall Uprising and served as a call to action for LGBTQ political activism. Because of the uprising, passivity was replaced by organized engagement and the gay rights movement gained strength and focus.

Organizing the First Pride Parade

Several months after the uprising, activists began putting together a march to commemorate the first anniversary of the Stonewall Uprising. At the Eastern Regional  Conference of Homophile Organizations, Craig Rodwell, Fred Sargeant, Ellen Brody, and Linda Rhodes proposed the event, which was to happen annually on the last Saturday in June. The proposal was approved and radically changed LGBTQ resistance.

Conference of Homophile Organizations, Craig Rodwell, Fred Sargeant, Ellen Brody, and Linda Rhodes proposed the event, which was to happen annually on the last Saturday in June. The proposal was approved and radically changed LGBTQ resistance.

One key aspect of the proposal was an insistence that there be no regulation on age or what marchers wore. In this period, LGBTQ activists held public walks, vigils, and picket lines but they were usually polite and held in silence. One such event was the Annual Reminder, a small, quiet march in Philadelphia. It was organized by Frank Kameny, a Harvard Ph.D., who was fired from his job in the federal government because of his homosexuality.

From 1965 to 1969, protesters demonstrated against the treatment of LGBTQ people by picketing outside Liberty Hall every July 4. To be non-threatening, Kameny insisted that business attire be worn: the men who took part had to don jackets and ties, while the women wore dresses. Similar demonstrations were held in front of the White House and in New York. The focus of Kameny’s Annual Reminders was on the law, not gay power or pride. Such events were intended to raise awareness about such issues as employment discrimination, anti-gay laws, and police brutality. As historian George Chauncey told the Washington Post, “The Annual Reminder was meant to remind the nation on its birthday of the promise of rights, liberty and the pursuit of happiness that had been denied to gay people.”

The planners of what was called the Christopher Street Liberation Day March turned this sedate tradition on its head. The Christopher Street Liberation Day Umbrella Committee included Rodwell, Sargeant, Brody, Rhodes, and Brenda Howard, who had a long history in statement-making grassroots activism, campaigning, and organizing. They organized a week-long slate of events to take advantage of the vast increase in interest in activism and newly formed organizations like the Gay Liberation Front, Gay Activists Alliance, and the Lavender Menace. The events related to Christopher Street Liberation Day were promoted via a mailing list that Rodwell and Sargeant had put together for Rodwell’s business, the Oscar Wilde Memorial Bookshop. Located on Christopher Street, it was the first gay bookstore in the United States.

Though the march was not originally called the NYC Pride Parade, as it is known today, one of the members of the planning committee suggested “Pride” as a slogan. L. Craig Schoonmaker, who was also part of the planning committee, suggested pride because gay people did have pride, even if they did not have power. The committee also came up with the march’s official chant: “Say it clear, say it loud. Gay is good, gay is proud.”

Marching in New York, Chicago, and California

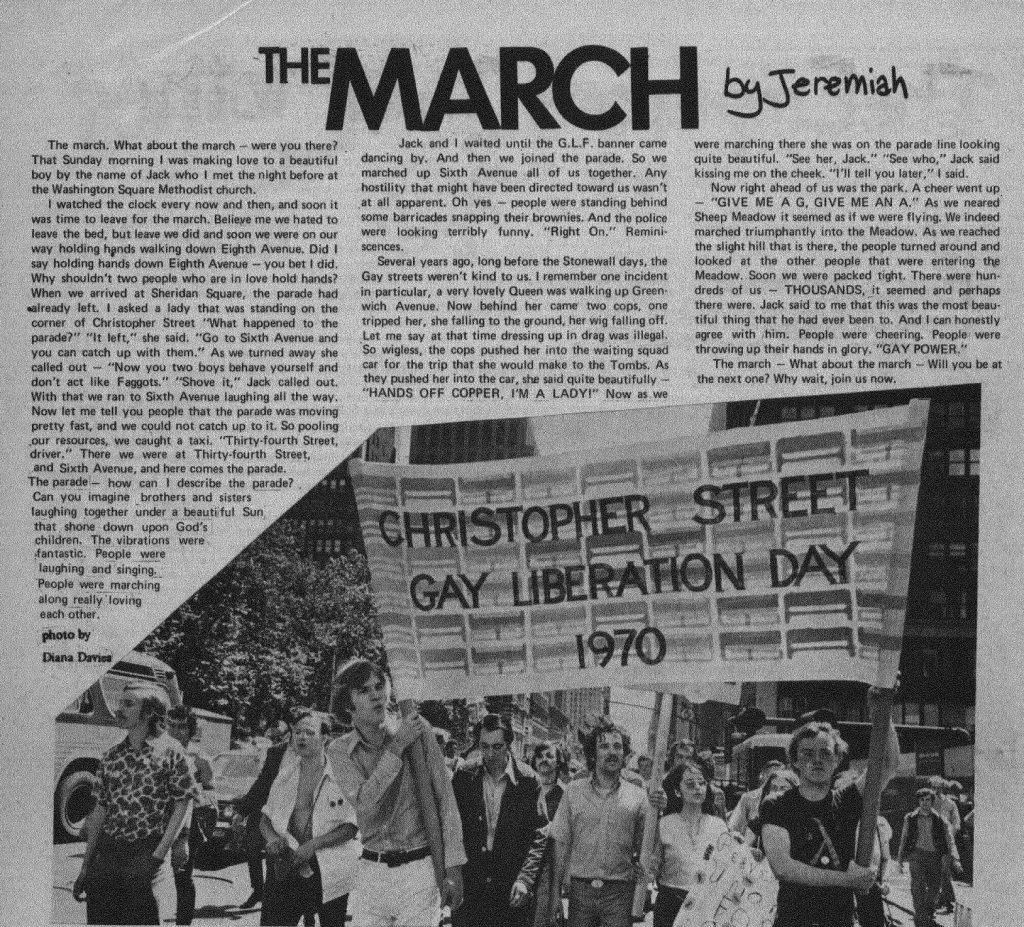

On June 28, 1970, the Christopher Street Liberation Day March took place over 51 blocks. The event began at Waverly Place in Greenwich Village and ended in Sheep Meadow in Central Park. It was simply a march of people carrying signs and banners, chanting the official chant. People joined the march as it went by, showing support for its message and those taking part. At its end, participants attended a gay-in, which was both protest and celebration, and was covered on the front page of the New York Times. The crowd at the rally in Central Park was estimated to be between 1,000 and 20,000 people.

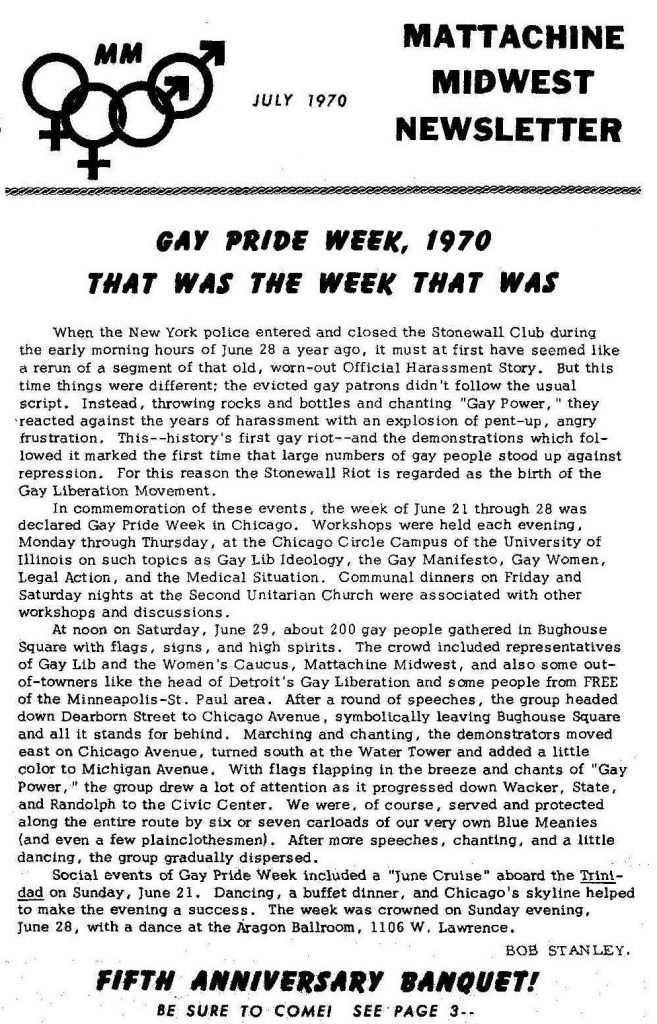

New York City was not the only city to hold events related to the one-year anniversary of the Stonewall uprising. After a week of activities that included a dance, workshops, and speeches in Chicago, the Gay Liberation Movement held a march on June 27, 1970, in which 150 people walked from Washington Square Park to the Civic Center. The official slogan of the march was “Gay Power.”

On the same day as the New York City march, both activists in Los Angeles and San Francisco held events. The Christopher Street West Association was given a permit to march on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles. This event was a permitted parade with an official route and street closures. It was the first permitted parade supporting gay rights. In San Francisco, activists organized a small march of about 30 people down Polk Street, then held a Gay-in at Golden Gate Park. Within two years, San Francisco had begun its own annual pride march, the Christopher Street West Parade, in support of gay rights.

Evolution of the Pride Parade

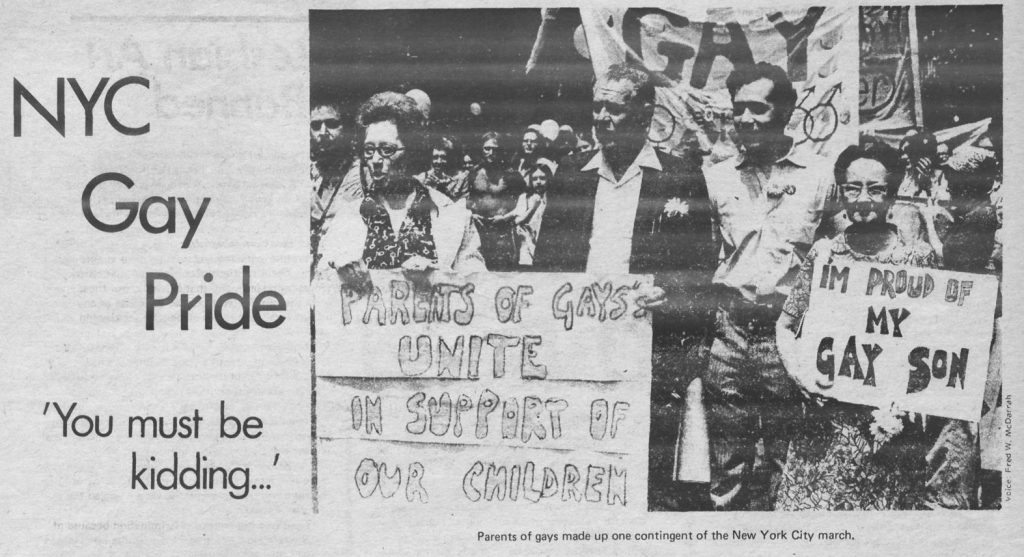

Organizing the first events was challenging, but it showed LGBT activists what was possible. Pride events, including Pride parades, became annual happenings in New York, Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles. Washington, DC, had its first pride parade in 1972. Dallas had its first pride parade that year as well, with 200 marchers and 17 decorated cars and floats. As the years progressed, the combination of advocacy and floats became the norm as seen in coverage of the 1973 Gay Pride Parade in Philadelphia. By 1973, the New York City Gay Pride march attracted a crowd of 12,000 to 20,0000.

It was in the mid-1970s that the marches and parades generally became known as Pride. The name was inspired by the chant of the original New York march and from a gay rights advocacy group, Personal Rights in Defense and Education, or PRIDE. In 1974, Los Angeles added a festival to the parade, which became the norm for pride celebrations in the United States. The rainbow flag was added in 1978, and first used in the Gay Freedom Day march in San Francisco. It originally had eight colors and was designed by gay activist Gilbert Baker. By the 1980s, most major US cities had a pride parade. New York City, Chicago, and San Francisco continue to hold their pride parades on the last weekend in June to honor the Stonewall uprising.

Many more cities around the world also hold their own Pride parades. In 2010, gay pride events were held in Brazil, Australia, and Russia. Even Pakistan has held a Pride parade, even though same-sex sexual contact is illegal in that country. One organizer of the first march New York City, Fred Sargeant, wrote in the Village Voice, “We could never have predicted that our efforts would lead to hundreds of millions of people gathering around the world.”

Meaning of Pride

From their earliest years, pride parades have been radical celebrations of gay liberation. Pride literally is an event that shows pride through an unfettered display of the depth and breadth of the

LGBTQ community. Even early on, dance parties, drag shows, contests, creative floats, celebrities, and extravagant looks were a part of Pride. Especially in the early years, marchers were also prepared for arrests and acts of violence against them.

At the same time, Pride has served as a visible act of cultural protest that brings the LGBTQ community and its supporters together in solidarity while working to change public attitudes through a joyful, public parade. Pride parades are also intended to inspire others by showing acceptance of self, an aspect especially relevant to young people who are embracing their sexual identity and marching for the first time. Pride parades continue to be a place of celebration, but also, remain symbols of resistance against those who want to deny and take away the rights of the LGBTQ community. To many in the LGBTQ community, pride parades are still necessary because equality has not been achieved.

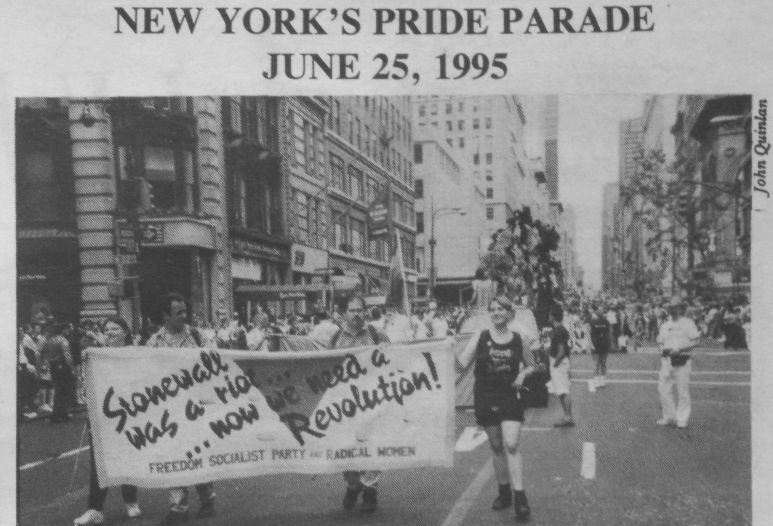

Additionally, pride parades reflect the tenor of the times and the state of the LGBTQ rights movement. For example, the 1970s Pride was often focused on advocacy, including in New York City. During the 1980s and early 1990s, Pride was angrier because of the AIDS crisis and the lack of government response to it. In the mid-2010s, pride parades included more families and children, reflecting the changes brought by marriage equality.

Presidential Support for Pride

Support for pride parades and other pride events has come from the highest political office. Bill Clinton was the first president to issue a proclamation declaring Gay and Lesbian Pride Month on June 11, 1999. Though George W. Bush declined to acknowledge Pride Month, Barack Obama declared LGBTQ Pride Month each June of his presidency. Obama also made the 7.7-acre area around Stonewall Inn a national park site. The Stonewall National Monument was the first LGBTQ national park in the United States.

By studying LGBTQ history, including the stories behind and around events like Pride and how they have evolved over time, we learn more about the forces that created these changes and contemporary reactions to them. Through the study of primary sources, readers and researchers better understand oppressed and underrepresented groups in the context of their times. The goals of the LGBTQ movement are also furthered because its quest for basic rights is now part of history books and other texts, giving more people insight into the LGBTQ experience and how it reflects and relates to the greater evolution of society.

Visit gale.com/pride explore the possibility of bringing a resource like Archives of Sexuality and Gender to your library.nike air max target heart