| By Gale Staff |

In the wake of the Stonewall uprising, the gay rights movement gained momentum and became a force that forever changed the status of gays and lesbians in society, perceptions about gender and sexuality, and culture itself. In the weeks and months after the police raided the Stonewall Inn in Greenwich Village on June 28, 1969, LGBTQ activism gained strength and focus, and became increasingly engaged with society. Through the sources found in the Archives of Sexuality & Gender: LGBTQ History and Culture Since 1940, Parts 1 & 2, this compelling story can be told with detailed nuance and depth. No other digital primary source archive features the same kind of complete information to reveal how the LGBTQ rights movement evolved since this milestone act of defiance.

The Power of Print

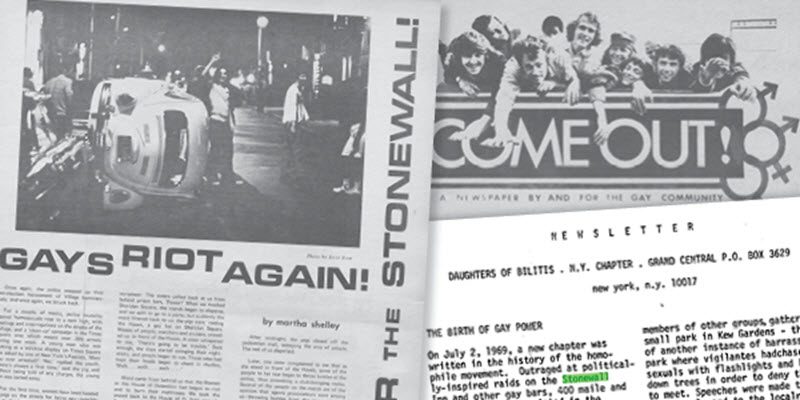

As the movement grew, periodicals for and by the gay community greatly increased in number around the country, especially in New York City. These publications played a key role in creating and defining “Gay Power” and helped the gay and lesbian community take a more public stance on gay rights. They tell the story of how the movement developed and was discussed by contemporaries; they also illustrate the many perspectives on gay rights that were offered within the gay and lesbian community. Though publications by and for the gay community had existed in the United States since 1924, it was not until after Stonewall that they greatly increased in number and circulation. Within three years of Stonewall, there were about 150 publications in the United States with a combined circulation of 250,000.

The Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society

Some of the LGBTQ groups that put out periodicals in the post-Stonewall era had been in existence for years. Both the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society had emerged in the 1950s. In the pre-Stonewall era, these groups used an orderly, low-key approach to convince the general public to take a more positive perspective on homosexuality. After Stonewall, however, this point of view changed, though each of these groups had a slightly different take on the emerging gay liberation movement.

Founded in San Francisco in 1955, the Daughters of Bilitis (DOB) was the first national lesbian organization in the United States and actively sought to change society's negative opinion on homosexuality. The group worked to eradicate discrimination for gay men and women institutionally, politically, and socially. DOB put out a number of publications, including the Ladder, a magazine that was published from 1956 to 1970. DOB chapters, including one in New York City, published newsletters to disseminate information and opinions with its local members.

In the New York City chapter's September 1969 newsletter, the Stonewall uprising is described in-depth in an article bolding proclaiming "The Birth of Gay Power" on page 1. The writer states simply, "On July 2, 1969, a new chapter was written in the history of the homophile movement." The riots and the response of the local gay community—including a Gay Power Vigil, speeches and discussions, and a public play that satirized heterosexuals—are described and praised. Throughout the article, the idea that the gay community has been activated in a way that it was not before is emphasized. As the article concludes, "The theme is self-respect, which we must assume ourselves, since it cannot be granted to us; and our rights as citizens, which we must demand. We are GayPower."

Not only did DOB define the burgeoning idea of gay power, the group was concerned with challenging the long-held belief of many in the medical establishment—and wider society—of the time that homosexuality was an illness. In the New York City chapter's October 1969 newsletter, an announcement on page 1 highlights a public meeting sponsored by the DOB in which two psychologists are scheduled to discuss how psychology is changing its point of view on homosexuality. Referring to the psychologists, the article emphasizes, "They believe an individual's life adaptation is of more importance than sexual choice." Furthermore, the article calls on members to bring straight friends and family to the public meeting, and outlines plans for the meeting to be advertised in high-profile mainstream publications like the New York Times and the Village Voice.

Originally formed in Los Angeles in 1951 as the Mattachine Foundation, the Mattachine Society became a national organization with local chapters in 1953 and one of the first gay and lesbian rights groups. After the group became the Mattachine Society, education, publications, and public relations became important ways for the organization to disseminate its original agenda of enlighten everyone in society—straight and gay—about the scientific facts about homosexual identity and behavior. The society's publications included a journal, the Mattachine Review, and newsletters. Unlike later gay rights groups, Mattachine took a reserved, polite tone and tactic in much of its action work.

Though the Mattachine Society's focus evolved after its national structure dissolved in 1961, the national chapter in San Francisco and branches bearing the group's name in other cities continued to actively seek change. The Mattachine Society of Washington focused on political change, challenging the discriminatory policies of the U.S. Civil Service in non-threatening fashion in the 1960s. The Mattachine Society of New York was challenged as the gay liberation movement took hold in the late 1960s and early 1970s. Because of its low-key style, the ideas of the new gay power movement and more radical gay groups were sometimes at odds with the New York chapter's perspective on how to achieve real change and equal rights.

In the Mattachine Society of New York's September 1969 Newsletter, the article on page 1 has a headline which asks "What Is 'Gay Power'?" In the article, the Mattachine Society describes itself as being comprised of "doddering oldsters" who are now being approached by younger activists who want to achieve "gay power" and "gay liberation" because of the Stonewall uprising. The article emphasizes that the Mattachine Society has long worked towards specific goals including full equality for homosexuals, related legal reforms, and an end to discrimination, so the terms gay power and gay liberation "were new to us" but "the substance was not." After describing the society's many achievements such as an end to police entrapment of homosexuals in New York City, the article acknowledges that these new slogans have value to the movement because "Homosexuals are human beings and as such entitled to the same basic rights as all other human beings." The article concludes on a positive: "If this represents 'gay power', fine. We want it."

Gay Power and the Gay Liberation Front’s Come Out

In contrast to the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, the magazine Gay Power as well as the organization Gay Liberation Front and its publication Come Out were created in the wake of the Stonewall raid and uprising. Though these publications took on very different perspectives on gay rights and community, they reveal how a younger generation perceived and reacted to contemporary events and demands for liberation. Unlike their predecessors, the publishers of these periodicals were not necessarily as focused on goals in the same way nor wanting to achieve acceptance through polite action. Instead, these periodicals show that the gay power movement was multi-faceted and that there were those who focused on financial gain as gays and lesbians sought to be informed about and become part of gay liberation.

After Stonewall, publisher Joey Fabricant created the New York-based magazine Gay Power. Taking its name from one of the main slogans of the post-Stonewall era, Gay Power claimed in its first issue in 1969 to be an outrageous, unapologetic voice of the young movement. In a statement on page 3, Fabricant declares, "For the straight, uptight politicians, bourgeois, and naive and maybe a pioneer here and there and yes, for you power freaks who adore exalting in the good of any cause, add to the list that of 'GAY POWER'. Watch it take to the road in the likes never seen before." Fabricant concludes, "Variety is still the spice of life and 'GAY POWER' is by and for all people. A people is what we shall exemplify first not in any 'half see how far we can get' subtle way, but in the best entertaining and educational way."

Despite such lofty pronouncements, Fabricant and his Gay Power proved to be a periodical devoted to exploiting the name of the movement to make money. Instead of covering the growing demand for gay rights among homosexuals and lesbians, highlighting meetings devoted to furthering the cause, or explaining how to get personally involved, Fabricant focused on advertisements (classified and displayed), astrology, and pornography. Though short-lived, Gay Power and Fabricant were regarded as undermining the very slogan from which the publication drew its name and the community it claimed to represent.

Fabricant and his magazine were criticized by others in the movement, including the newspaper Come Out. In its first issue in November 14, 1969, an article on page 3 titled "Joey Fabricant Perverts Gay Power" outlines the issues with Fabricant and Gay Power. The unnamed author explains that Fabricant was only concerned about increasing his profits and self-promotion, "to cash in on the new interest in homosexuality via the new freedom of the press." The author also claims, "I called it 'junk literature' and spoke of it as being 'subtly harmful,' in that it underscored all of the cliches of homosexuality. Many straights bought the publication out of curiosity, and it only confirmed their negative image of the homosexual as a disturbed, little-boy-molesting, half-witted freak." Furthermore, Fabricant attacked homosexuals by name in print without regard for any truth. In doing so, exposed their names to the public in a way which had negative impacts on their lives, careers, families, and mental health. Citing his personal power and the power of his readership, the author of "Joey Fabricant Perverts Gay Power" concludes by calling for a boycott of Gay Power and any businesses that advertise or sell it.

Unlike Gay Power, Come Out was very concerned with building positive relationships and carried the empowering tagline "A Newspaper By and For the Gay Community." Come Out was an official publication of the organization the Gay Liberation Front (GLF), which was formed in New York City shortly after the Stonewall uprising. With a name inspired by the National Liberation Front of South Vietnam, the group's gay and lesbian members identified with the counterculture movement of the late 1960s and early 1970s. GLF was antiwar, politically left, revolutionary embracing, and often radical. The perspectives and attitudes of GLF and its members were in contrast to older homophile organizations like the Daughters of Bilitis and the Mattachine Society, which were somewhat leery of the upstart, uncompromising activists of GLF. Though GLF in New York essentially fell apart by late 1971, it played a key role in publishing the perspectives of gay liberationists, sharing information about other gay consciousness-raising groups, spreading ideas about gay power and gay liberation, and providing a model for the political activists that followed.

On page 1 of Come Out's first issue, the perspective of GLF and the newspaper's editorial staff was clear: be supportive of fellow gays and demand change. This opening statement proclaims that Come Out "dedicates itself to the joy, the humor, and the dignity of the homosexual male and female." Furthermore, "COME-OUT has COME OUT to fight for the freedom of the homosexual … to provide a public forum for the discussion and clarification of methods and actions necessary to end our oppression." The statement also notes that "We shall aggressively promote the use of the very real and potent economic power of Gay people throughout this land in order to further the interests of the homosexual community."

The writers and editors of Come Out fearlessly criticized anyone that they believed undermined the gay community. For example, on page 9, they lambasted the Village Voice, the leading alternative press publication in New York City, for its indifferent reporting on Stonewall and its advertising policies. Writers Mike Brown, Michael Tallman, and Leo Louis Martello assert, "Their handling of the first Gay Riots in history read like a copy of the New York Daily News. Instead of being concerned about the civil rights of the Gay minority they were preoccupied with the uptight establishment's reaction to the riots." The authors also note that Village Voice censored classified ads purchased by GLF ahead of Come Out's publication. The term "gay" was removed from an ad because it was considered obscene, and "homosexual" was also not an acceptable alternative for the same reason.

In response, the members of GLF began legal proceedings and organized a picket line outside of the Village Voice office. Through their actions, gay and homosexual became acceptable words to use in ads, and ads could no longer be changed after purchase. Though GLF could not convince the Village Voice to alter its editorial position that writers could say what they liked about anyone—even if it was bigoted and used derogatory language and ideas—the organization had the right to publicly call out and protest what was published in Village Voice. Such actions show how the empowered gay community did not fear being assertive to gain forward progress.

Come Out also featured diverse voices of the gay liberation movement. In an article titled "BITCH: Summer's Not Forever" on page 12, Marty Stephan, a self-described "drag butch," muses about the events surrounding Stonewall and the wider gay liberation movement that was being formed. Stephan discusses moments of pure joy related to the Washington Square rally after the Stonewall raid, stating "It was a beautiful thing to see, 500 of us marching, chanting, clapping in cadence — us dammit, after all these dead years." However, she also expresses a desire for more, a coming together "simply to enjoy the freedom of being together, to rejoice in each other, to get our heads together."

In relation to employment and GLF itself, Stephan wonders about the idea of social acceptance that was a key aspect of the gay liberation movement: “What the hell is social acceptance anyway? Does it just mean not being hassled and not being starred at anymore? Does it mean being dug by people who didn’t dig you before, just because you were gay? Or does it mean courteous treatment where you spend your bread?” After noting she had experienced being dismissed by other members for GLF for who she was, she calls on them to respect the lifestyles of all gays and lesbians. Stephan concludes, "Perhaps the best definition of social acceptance is just to have your own life style without comment from anyone — straight or Gay."

Outside of New York, the Song Remained the Same

The impact of Stonewall on the status and position of gays was appreciated by groups outside of New York City as well. Philadelphia’s Homophile Action League (HAL), a pre-Stonewall organization founded there, printed an editorial that analyzed the events of Stonewall uprising on page 1 of the August-September 1969 issue of its newsletter. Titled “Give Me Liberty Or …..,” editorial explained what happened on June 28, 1969, and the days after, as well as the way the gay community was organizing itself. The authors consider why Stonewall was raided in the first place: “If the Stonewall has indeed been operating illegally, what collusion between the Mafia and the police has protected it in the past? … And, must homosexuals remain helpless pawns in the hands of these de facto ruling powers?”

Though HAL had more in common with the Mattachine Society than groups formed after Stonewall in attitude and outlook, this editorial concludes on a truth proven throughout these sources: “Whatever the outcome of what has been called the ‘first gay riot in history,’ things will never be the same again.” Through the breadth of articles in all these publications and others available—in as much of their entirety as possible—in the Archives of Gender and Sexuality: LGBTQ History & Culture Since 1940, it is clear that the gay rights movement was full of different points of view on how to publicly pursue change, and what the ideas of gay power and gay liberation fundamentally meant in the post-Stonewall era. To read through entire issues of newsletters or periodicals on the Archives of Sexuality & Gender is to see the many forms of expression—big and small, obvious and subtle—that these perspectives take as gay rights and freedoms became reality.

Jordan Ανδρικά • Summer SALE έως -50%