| By J. Robert Parks |

The phrase “trial of the century” has become a common trope for satirical outlets that comment on the news. The adoption of the phrase occurred primarily through the twentieth century as newspapers and, later, radio and television outlets dedicated resources to covering dramatic proceedings in U.S. courtrooms. The 1921 trial of Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti on robbery and murder charges, the 1951 trial of Julius and Ethel Rosenberg on federal espionage charges, and the 1995 trial of former athlete and entertainer O. J. Simpson on murder charges are all candidates for the distinction. But certainly one of the most culturally significant U.S. trials of the twentieth century was the Scopes Trial, which took place 100 years ago this month. Teachers and librarians wanting to highlight the various topics raised by the trial will find plenty of resources in Gale In Context: U.S. History.

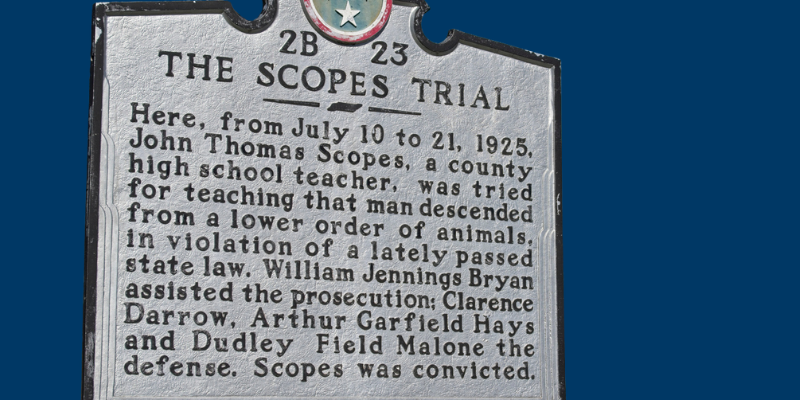

The Scopes Trial was officially known as the State of Tennessee v. John Thomas Scopes but it was also called the Monkey Trial, as John Scopes was accused of teaching evolution in his high school class. Charles Darwin’s theory of evolution had become a more popular topic in U.S. schools, but many Americans believed that it contradicted their religious beliefs. The Tennessee legislature had passed a law earlier in 1925 that made it illegal to teach evolution in public schools, and the American Civil Liberties Union offered to defend any teacher who was prosecuted under the law. Scopes took up the challenge, volunteering to teach on the subject and purportedly even encouraging his students to testify against him.

The trial was ready-made for media attention, but it became even more of a sensation when two of the more famous figures of the day decided to get involved. William Jennings Bryan had been the Democratic presidential candidate in 1896, 1900, and 1908, as well as Secretary of State under Woodrow Wilson. In the 1920s, Bryan turned his focus to religion, including preaching on the radio and fighting the growing belief in evolution among Christians, and he was named a special prosecutor for the trial. The famous defense attorney Clarence Darrow was excited to go up against Bryan and defend Scopes and the right to teach evolution.

Darrow was at a disadvantage, however, in that Scopes’ guilt wasn’t in doubt; he had violated the Tennessee statute. Furthermore, scientific experts on evolution weren’t allowed to testify, so Darrow made the decision to focus on whether the Bible should be taken literally. The literal interpretation of the Bible wasn’t a new idea, but it was the foundation of Fundamentalism, a wing of Protestant Christianity that became popular in the early twentieth century as a reaction to more recent ways of thinking about religion and science.

Neither the beginning of the trial, which was dull, nor the end of the trial, which was anticlimactic, are why we remember it today. Instead, the trial’s defining moment was when Darrow challenged Bryan to take the stand to defend a literal interpretation of the Bible, and Bryan decided to honor the request. Bryan was a brilliant orator and thought he could provide a strong defense. Besides, scores of outside journalists were covering the proceedings, including H. L. Mencken, and the trial was being broadcast on the radio. Bryan wasn’t one to turn down that kind of publicity. Unfortunately for Bryan and his followers, Darrow was better prepared, and Bryan struggled to respond when Darrow highlighted various passages of the Bible that seemed to defy a literal interpretation. Popular culture remembers Darrow as the winning attorney even though his client was convicted. (Scopes never spent a day in jail, and his fine was later set aside on a technicality.)

As has often been the case in U.S. history, it was writers who shaped our understanding of interpretations of the impact of the Scopes Trial. Mencken’s caustic coverage, especially of Bryan, highlighted the contrast between science and faith. Thirty years later, the play Inherit the Wind, by Jerome Lawrence and Robert Edwin Lee, provided a fictionalized version of the play that reinforced Mencken’s dichotomy. Although the play isn’t performed as often as it used to be, its theme of the battle between intellectual freedom and demagoguery might make it just as relevant in the twenty-first century as it was when the trial itself was held.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale In Context: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.