| By Gale Staff |

Long before pastel eggs and chocolate bunnies became seasonal symbols, cultures worldwide welcomed the arrival of spring with their own festivities celebrating renewal and new life. Over the centuries, these early traditions inspired many of the customs we today associate with Easter.

For young learners, familiar Easter traditions provide a framework for broader discussions on how cultural practices morph across time, adapting to reflect new beliefs, ideas, and contexts.

Finding the right resources to make these complex ideas approachable and engaging for young minds can be as simple as signing into your Gale In Context: Elementary account. From the Easter topic page, you will find curriculum-aligned, educator-approved content, I Wonder questions, visual topic trees, leveled summaries, and more. These features are crafted to capture students’ imaginations, making advanced topics approachable and fun.

If you’re looking to introduce your elementary students to the fascinating cultural exchanges that have shaped Easter, we’ve curated a selection of materials from Gale In Context: Elementary, tracing back the roots of some of the holiday’s eggstraordinary lore.

Ancient Celebrations of Spring

For pre-industrial societies, surviving winter required careful planning—and, in some cases, a bit of luck. Wintertime often meant a scarcity of food and, depending on the climate, relentless cold.

As the days grew longer and the earth began to thaw, the return of warmth and abundance was cause for profound gratitude. To make sense of the forces they didn’t understand, ancient peoples created mythologies that explained natural phenomena, including changing seasons.

Ishtar’s Descent and Resurrection

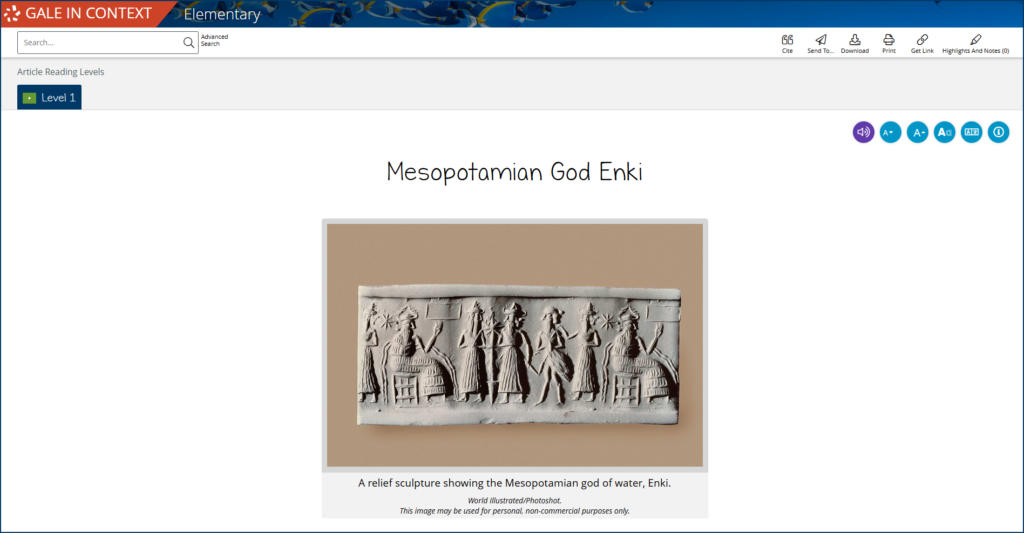

In the cradle of civilization, nestled between the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers, ancient Mesopotamia looked to the myth of Inanna—later known as Ishtar—to explain seasonal cycles.

In Sumerian mythology, Inanna, goddess of love, fertility, and war, ventured into the underworld in search of her lost love—Dumuzid in Sumerian or Tammuz in Babylonian—who was the god of agriculture and flocks. The goddess’s journey was long and challenging, but when she finally found him, their joy at being reunited made the Earth blossom back to life.

However, the two needed to find a compromise to secure Dumuzid’s release. So, for six months of the year, Dumuzid descended from his place in the heavens, signaling the arrival of autumn and the oncoming winter. When Dumuzid returned to the sky, he brought fertile spring and summer back to the Earth.

Activity Idea: Use the Innana myth to introduce students to how myths and legends connect to real-world phenomena, like the changes in the seasons. How does Inanna’s journey mirror the natural changes they see during different times of the year?

Older or more advanced students can explore other springtime myths from around the world—such as the Greek myth of Persephone and Demeter, Egypt’s Osiris, or the Norse Idun and her apples—to uncover shared themes and patterns across cultures.

The Germanic Origins of Easter Symbols

Between approximately 472 and 800 CE, Germanic groups—such as the Goths, Vandals, and Franks—migrated into regions including the British Isles, Germany, and Scandinavia.

As these groups spread across vast territories, their traditions became more localized, with each community adapting its polytheistic beliefs and practices to suit new environments and daily realities. These new traditions reflected the challenges of living in diverse, isolated regions. As such, each village or tribe maintained its own rituals celebrating spring’s arrival.

Collectively, historians have applied the term “Paganism” to describe the wide range of pre-Christian spiritual practices across Europe, though these beliefs varied greatly depending on region and culture.

Ostara, Eggs, and Hares

Twice a year, the Earth’s alignment is such that the axis is not tilted, and the entire planet experiences day and night in equal measure. This is called an equinox. For these Germanic communities, the vernal equinox, which occurs around March 20, was a day to honor Eostre or Ostara for her role as the bringer of light and abundance.

Ostara’s name is derived from the Proto-Germanic word Austrǭ, meaning “dawn.” Her connection to seasonal cycles made her a highly revered figure in these agricultural societies, where people relied on her blessings for a bountiful harvest.

Some of the symbols we associate with Easter today, including the hare, or rabbit, trace back to Ostara—though the connection is more of a well-informed theory than a hard fact. Scholars recognize the hare’s importance as a fertility symbol in ancient Germanic traditions and have tied that to Ostara’s role as a goddess of abundance, leading to the belief that her symbol may have been a hare.

In the 19th century, a German scholar referenced the Easter Hare, a South German folkloric figure believed to bring eggs to children during Easter. While discussing this custom, he speculated that “the hare must once have been a bird, because it lays eggs.” This playful remark was later expanded into a story of Ostara transforming a bird into a hare, granting it the ability to lay eggs during her festival. Although this legend depends on modern invention, it has persisted nevertheless.

Discussion Idea: Ask students to reflect on what Easter and the changing of the seasons mean to them. Encourage them to think about whether they associate any of the symbols or stories, like the hare or eggs, with their own traditions.

Older elementary students can also discuss why they think holidays like Easter continue to be widely celebrated today by people from diverse backgrounds. What aspects of the holiday bring communities together today?

Passover and Easter

Though Christianity would eventually adopt many Pagan symbols into its Easter celebrations, the Jewish holiday of Passover is the primary foundation upon which Easter was built. Passover commemorates the Israelites’ liberation from slavery in Egypt and takes its name from the story in the book of Exodus.

According to the Torah, the basis for the Old Testament of the Christian faith, God “passed over” Israelite homes marked with lamb’s blood during the final plague, sparing their firstborn and securing their freedom from Egyptian bondage.

This theme of sacrificial deliverance is carried into Christian theology through the events of the Last Supper, which Jesus shared with his disciples as a Passover meal shortly before his crucifixion. For Christians, Jesus’s death is seen as a fulfillment of the Passover story—the “lamb of God” whose sacrifice is likened to that of the lamb whose blood spared the Israelites.

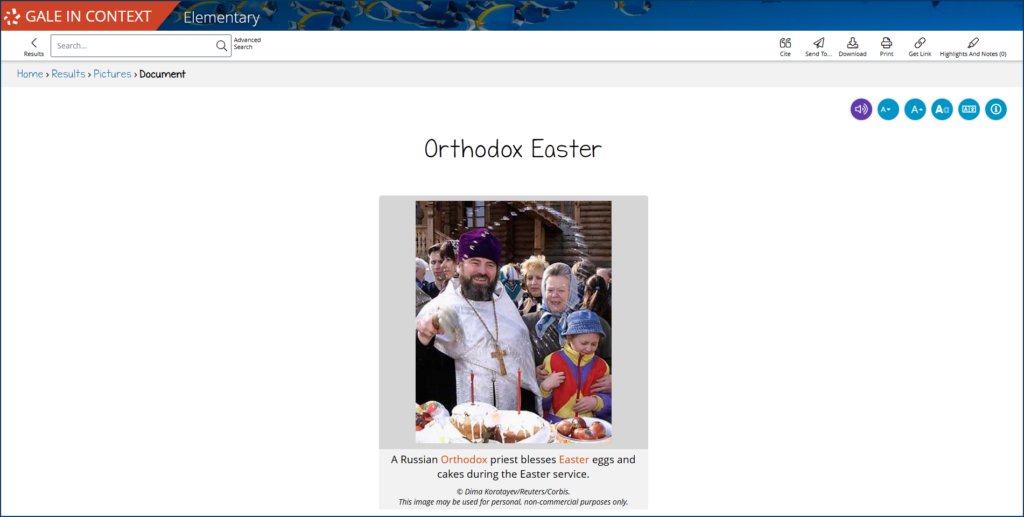

Pascha and Orthodox Easter

In the early centuries following the crucifixion, Christians adapted the Jewish holiday into a springtime celebration called Pascha, derived from the Hebrew word for Passover, Pesach.

Over time, Orthodox Easter (still called Pascha in many Eastern Christian traditions) became distinct from Western Easter. Churches in regions such as Greece, Turkey, Russia, and the Middle East retained the festival’s close alignment with Passover, calculating the date of Pascha based on the luach ha’ivri, or Hebrew lunisolar calendar. This system means that Passover always falls on the 15th day of Nisan, the Hebrew month in which the spring equinox falls.

Orthodox Easter is always celebrated after Passover, sometime between April 4 and May 8, to reflect the biblical timeline of Jesus’s crucifixion and resurrection, which occurred during and shortly after Passover. This date can fall as much as a month after Western Easter.

Western Easter

When early Christians adopted the Jewish festival of Passover to celebrate Jesus’s resurrection, the timing of Easter naturally aligned with the Jewish calendar. However, the Church wanted to establish a unified identity distinct from Judaism.

The First Council of Nicaea in 325 CE decided Easter would no longer align with Passover but, instead, be based on the first Sunday after the first full moon following the spring equinox. This calculation was based on the Julian calendar, which was the standard of the time and mirrored the timing of many Pagan spring festivals.

Over time, cultural exchanges between Christian communities and Pagan converts saw Easter celebrations incorporating Paganism’s seasonal and fertility themes. Eggs, for instance, were reframed to represent the empty tomb of Jesus and the promise of new life. And, of course, Eostre’s name was used as the basis of the word “Easter.”

Discussion Idea: Ask students to think about how different traditions, like Passover and spring festivals, came together to create Easter. Why do they think people borrow ideas and symbols from other cultures, like eggs and hares, when creating new holidays? How might sharing and combining traditions help bring people together and make celebrations more meaningful?

From history to holidays and beyond, Gale In Context: Elementary offers academically rigorous content tailored for grades K-5, making complex concepts approachable and engaging for young learners. Contact your Gale representative today to learn more or request a trial!