During Black History Month, we honor African Americans who profoundly impacted the course of American history. During Reconstruction—an era that lasted from about 1865 to 1877—African Americans gained new political and legal rights that were implemented with the support of the federal government. A number of activists redefined how blacks participated in American politics, society, and culture, especially in the South. Men like Hiram Revels, Robert Elliot, and Joseph Rainey were part of the vanguard of black political leadership in this period.

These activists accomplished many significant objectives despite facing harsh racism and having their efforts undermined by Southern whites who felt threatened by newly empowered black citizens. Though African Americans saw many of the gains made during Reconstruction rolled back in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the actions of these early African American leaders inspired those who followed them and carved a path for civil rights leaders in the mid-twentieth century.

Black Activism in Reconstruction

Although African American slaves were freed by the end of the Civil War, they were not immediately given legal and political rights under President Andrew Johnson. During the first years of Reconstruction, blacks formed Equal Rights Leagues in the South to demand equality under the law, including the right to vote, and to fight oppressive black codes—laws that restricted the lives of newly freed African Americans in various ways.

From 1867 to 1877—the period known as Radical Reconstruction—black Americans were given many basic rights by Congress, such as official citizenship and the right to vote. As more African Americans were allowed to participate in American political life, organizations like the growing Union League supported black political activism in the South. Beginning in 1867, blacks took part in state constitutional conventions for the first time and comprised the vast majority of Republican voters in the South.

During Reconstruction, about 2,000 African American men served in political office. Hundreds of blacks held local offices in the South, more than 600 were elected to state legislatures, and 16 served in Congress. To take these posts, they often had to win elections plagued by violence and fraud. Southern whites used many forms of intimidation to oppose black voters, politicians, policies, and rights. The Ku Klux Klan and other white supremacy organizations also attacked Republican leaders and African Americans during this period, killing at least 35 black officials.

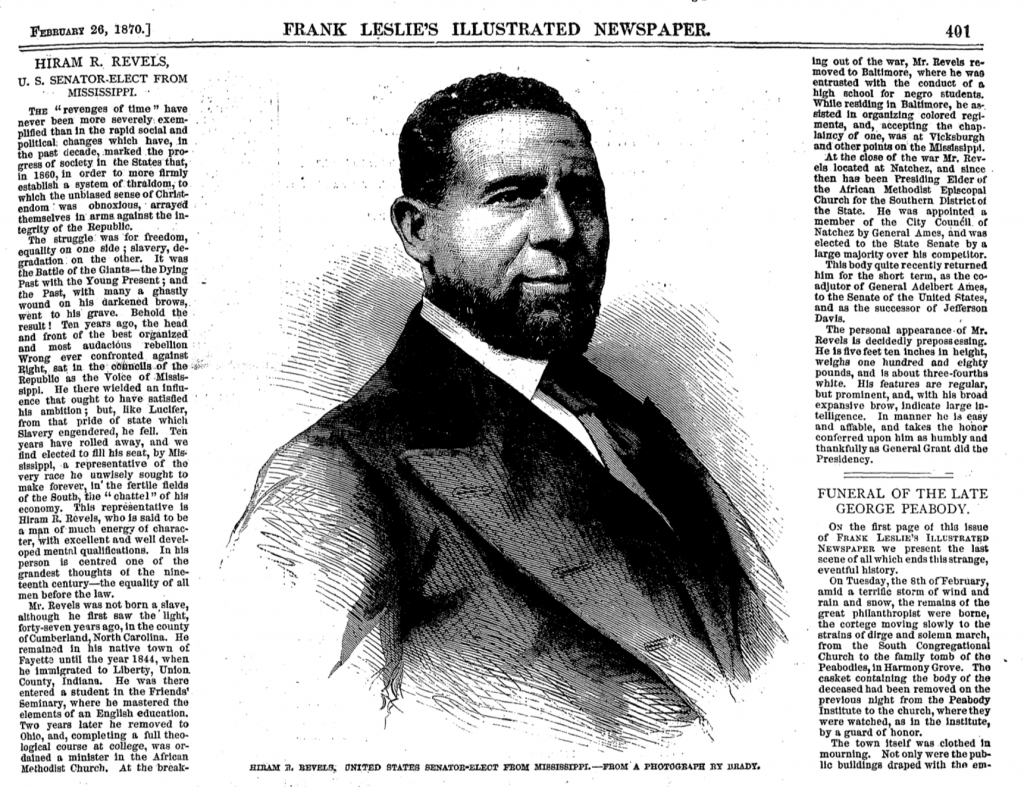

One of the most influential black leaders during Reconstruction was Hiram Revels, the first African American elected to serve in the U.S. Senate. Revels represented the state of Mississippi. Like many black leaders of this era, he had acquired leadership experience in the church and the Union Army. Revels had been born free in North Carolina. Educated in Illinois, he was a preacher in the Midwest and a black regiment’s chaplain in the Union Army during the Civil War. He went to Mississippi in 1865 to work for the Freedmen’s Bureau.

In January 1870, Revels was elected to the U.S. Senate by the Mississippi state legislature, to complete the term of a seat left vacant since the Civil War. When elected, Revels was widely praised. His biography and personal description were published in newspapers across the country, such as the Wisconsin State Register and the Little Rock, Arkansas, Morning Republican. In the Dover Gazette & Strafford Advertiser, Revels was lauded as “a man of much energy of character, with excellent and well developed mental qualifications. In his person is centered one of the grandest thoughts of the nineteenth century—the equality of all men before the law.”

Revels served just one year in the Senate because he was not chosen for a full six-year term; he was replaced by a white Republican and former Confederate general. Though Revels and other black politicians usually did not have the same power as white politicians in office, they successfully supported and advocated measures for racial equality.

Robert Elliott

Another important African American politician of the Reconstruction era was South Carolina’s Robert Elliott. Like Revels, Elliott was well educated. Born in England, he attended schools there and trained as a typesetter. He came to Boston in 1867 and moved to South Carolina later that year. Elliott became involved in politics in 1868 as a delegate at the state constitutional convention. African Americans in South Carolina had been organizing politically longer than those living in most other states, and many blacks were elected to early state conventions there. At the 1868 convention, Elliott was one of 78 black delegates. He stood out for his strong oratory skills and passionate support for compulsory education.

Subsequently, Elliott held a county office, was elected to both the state house and state assembly, and was appointed the assistant adjutant general before winning a seat in the U.S. House of Representatives in 1870. In Congress, Elliott faced several challenges. Unlike other African Americans serving in the House at that time, he was dark skinned and was more radical in his passionate support for black civil rights. Consequently, he and many other African American congressmen were refused service in various establishments in Washington, D.C. Elliott supported a bill that would ban such forms of public discrimination.

Joseph Rainey

Also a politician from South Carolina, Joseph Rainey was the first African American to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives. He was a member of the House from 1870 to 1879, the longest tenure of any African American legislator during Reconstruction. In April 1874, Rainey experienced another first, becoming the first black man to preside over a session of the House.

Unlike Revels and Elliott, Rainey had been born into slavery, though his father bought his family’s freedom when Rainey was a child. Receiving a limited education, Rainey was trained as a barber, then was forced to serve in the Confederate Army until he and his family escaped to Bermuda. Returning after the end of the Civil War, Rainey became active in Republican politics in 1867 and won a seat in the state senate in 1870. Shortly thereafter, he was elected to complete a congressional term for a U.S. Representative who resigned due to scandal. Winning several subsequent elections on his own—though not without legal controversy—Rainey advocated for both his black and white constituents, but focused especially on civil rights.

After leaving office, Rainey remained politically active even as African American rights eroded. In January 1881, he took part in the Cleveland conference of colored men which was organizing a push for African American rights under the newly elected president, James Garfield. In an open letter to Rainey and other participants published in the Lynchburg Virginian, Arthur St. A. Smith wrote, “gentlemen, let me say that if you, the present leaders of our people do not secure some substantial recognition at the hands of Gen. Garfield, you might as well take back seats, for you gentlemen, at least, can never rally the negroes to the Republican polls again ….”

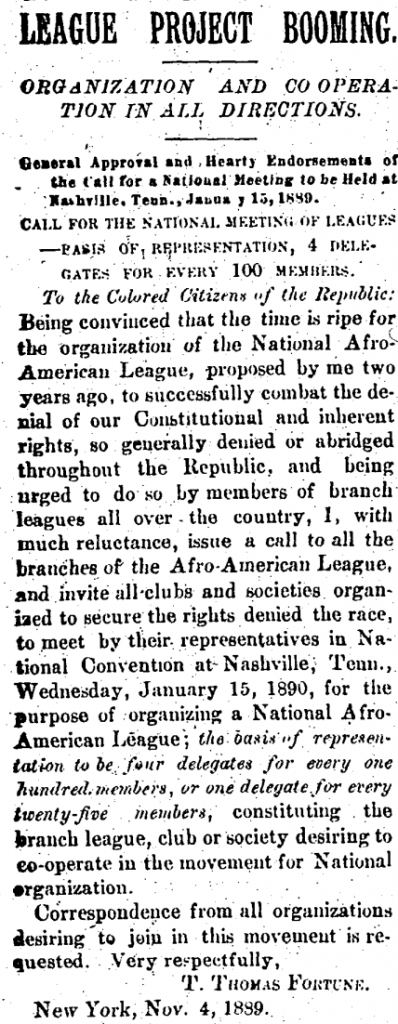

After Reconstruction ended, other black political leaders continued to fight for the civil rights and the legal justices that were being denied to African Americans. Many more conventions were held and organizations were formed on state and national levels, to help coordinate efforts and expand the political footprint of African Americans and their supporters. One such meeting was held in November 1889. According to the Milwaukee Daily Sentinel, the Wisconsin Civil Rights league was created and began framing a civil rights bill to present to the state legislature. Another gathering was held in early 1889 to form a National Afro-American League that was intended, according to T. Thomas Fortune in the New York Age, “to secure the rights denied the race.” Although the fight for civil rights did not end in the nineteenth century, the work of courageous black Americans such as Revels, Elliott, and Rainey helped to introduce a new democratic order and forever changed the political and social landscape of the United States.Nike Air Jordan Retro 1 Red Black White – Buy Air Jordan 1 Retro (white / black / varsity red), Price: $60.85 – Air Jordan Shoes

0 thoughts on “Asserting Equality: Black Political Activism During Reconstruction”