| By Brittany Pope, Gale Ambassador at the University of Wyoming |

Bias exists in everything—even the most careful journalist or observer will have an element of bias because human perception is subjective. By understanding how bias can creep even into objective works, those who wish to use primary and secondary sources in their academic and professional work will be able to assess the motivations, limitations, and subjectivity of their sources. Understanding bias means that the user can avoid spreading misinformation or prejudiced lines of thought unchallenged. In that same measure, bias isn’t always a terrible thing, as it does have use in processing the overload of information everyone is subjected to and in making snap decisions. For example, we use bias to avoid falling for a sketchy email that claims you won a lottery in a country you’ve never been to, or to avoid chasing down irrelevant topics when searching for sources for your papers. However, even “good biases” must be examined and acknowledged to achieve impartiality.

For this article, instead of going over the common argumentative biases such as confirmation bias or anchoring bias (as there are numerous articles that cover the root cause and specific incidents of bias), I will talk about the way those biases appear in media. I will divide these appearances into three camps: open bias, hidden bias, and personal bias. Open bias is when the source does not hide their affiliations and preferences. For example, a politician’s press release is an open bias as they clearly state their positions for and against. Some periodicals will also openly support the passage or rejection of certain laws, endorse politicians, or even declare party affiliation. Hidden bias is when a source does not openly declare their affiliations or preference but will attempt to influence their readership toward their point of view by feigning a more neutral position. Personal bias is more common in personal and academic correspondence, where it’s individuals, not institutions, that express a biased opinion; these often appear in letters, editorials, and other forms where the bar for impartiality is much lower.

Open bias: Wearing politics on your sleeve

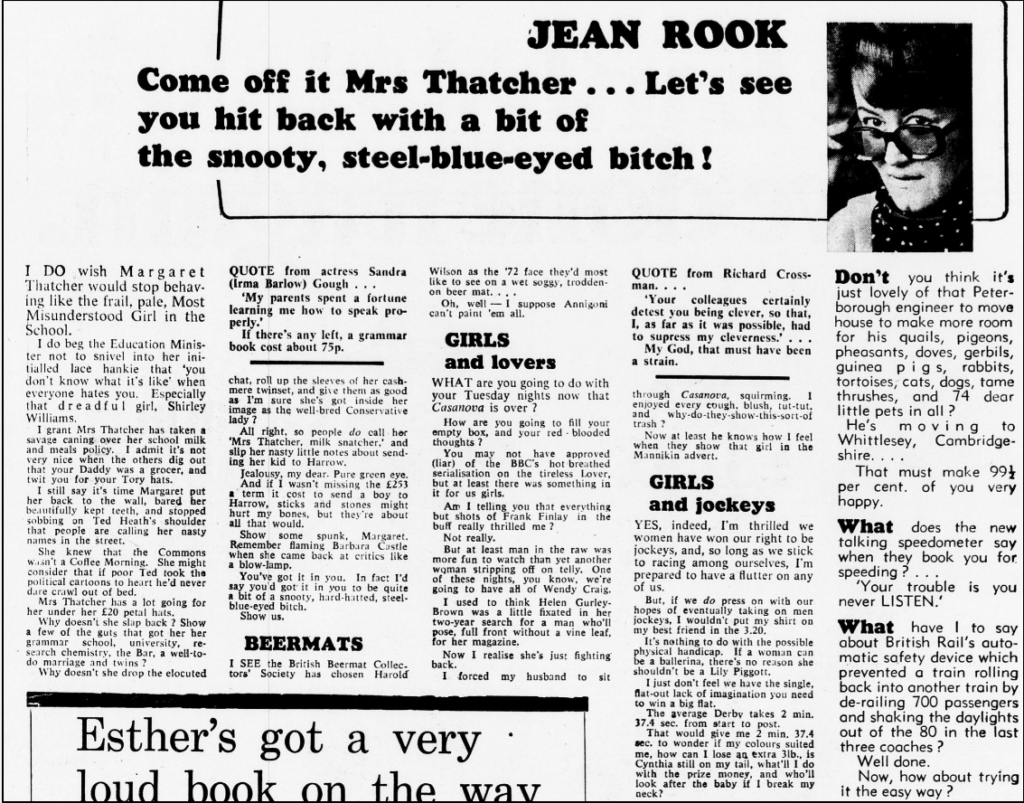

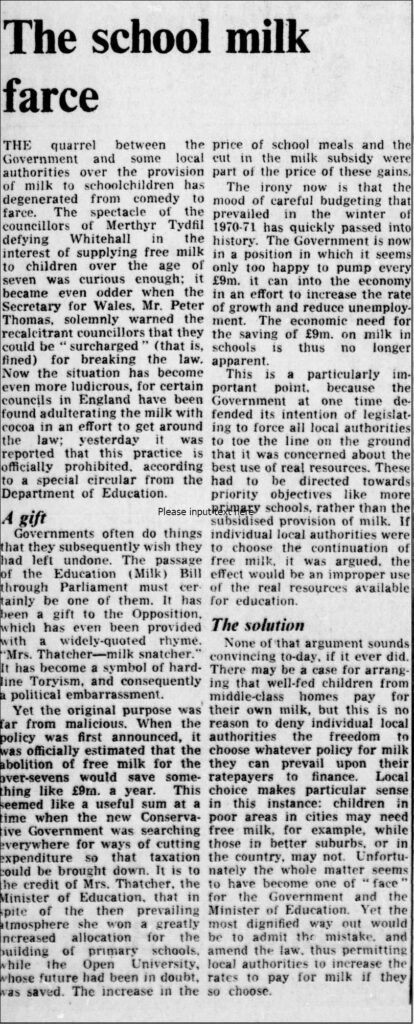

Open bias is the easiest to detect, as they are open about their goals and political and social leanings. A nonpolitical example of open bias is a press release by a corporation, as they will naturally be inclined to view and talk about themselves in the best light possible; but newspapers can also have biases and take pride in it. Several British newspapers are openly biased in the sense that they aren’t shy about their preferred party affiliation or stances on issues such as immigration. One good way to compare the political leanings of various papers is to go back in time and examine how the papers covered Margaret Thatcher, the former prime minister whose reign is so starkly Tory that there’s perhaps no person in Ireland and the UK who doesn’t have a strong opinion on her tenure. It seems that the only thing anyone can agree on about Thatcher is that her time was controversial and completely changed British politics. A good example of open bias is coverage of her decision in 1971 (as secretary of state for education and science) to withhold milk from schoolchildren over the age of seven. The Daily Mail—a right wing and strongly Tory paper—either approved of it or encouraged Thatcher to hit back at her critics, while the neo-liberal Financial Times—which tends to support a tilt between Tory and Labour—was more critical of what they perceived as overreach, and the reaction to “milk snatching” is framed as far more understandable rather than out of “jealousy,” as Jean Rook implied in her Daily Mail piece. When you are uncertain as to the specific social and political leanings of a publication, an effective way to assess them is to look up their historical endorsements of politicians or reporting of common hot-button issues such as immigration and LGBT+ rights.

(Left: The Daily Mail editorial with noted early Thatcher supporter Jean Rook, originally published on December 15, 1971, from The Daily Mail Historical Archive, both an example of open and personal bias. Right: A January 5, 1972, Financial Times article covering the local council pushback against the edict, from Financial Times Historical Archive.)

Hidden bias: “Some people say bias isn’t real—here’s what the experts say …”

Hidden bias is perhaps the most dangerous type, as it’s a bias with a hidden agenda—thus the name. Hidden bias attempts to appear impartial, but the media seeks to sway public opinion and policy toward their cause by careful use of language, imagery, and timing of missives and reports to maximize impact. One nonpolitical example is advertisements that try to disguise themselves as nondescript consumer or “brand” reviewers, feigning the veneer of impartial expertise and consumer concerns to talk up their product. Newspapers, network channels, and internet sites also similarly hide their bias. A common factor in many hidden bias sources is the use of weasel words such as “some people say” or “many outlets report” without citing specific names or organizations to avoid admitting their source is unreliable, too close to the issue to be trusted, or worse—completely fabricated. Unscrupulous periodicals will also run editorials as factual news articles without labeling them as opinion pieces. To tell an unmarked editorial from a news article, one should watch for “I” words and emotional language.

(Philip Howard complaining about the use of weasel words in newspapers back in 1982, from The Times Digital Archive.)

When reading an article, is it quoting a specific person? If not, there’s a good chance it might be weasel words at work. Now, is the article quoting the exact words of a person or organization, or is it summarizing or taking a segment out of a much longer statement (as indicated by ellipses on either side of the quote)? If the latter, then it’s likely they are either attempting to distort the actual statement or choosing to take something out of context to fit the agenda of the article. Another way to avoid falling for hidden bias is by becoming familiar with the style guides for newspapers. Journalists that attempt to report with integrity will adhere to style guides, while hidden bias pieces tend to violate them, as style guides strive to achieve neutral and noninflammatory language when referring to controversial topics, how sources should be quoted, and other points of reference to maintain journalistic integrity. The Associated Press style guide is the baseline for American news associations, but other nations may have their own guides; sometimes individual news outlets and universities have their own guides, such as the BBC or Oxford University.

Personal bias: “Well, that’s just my opinion”

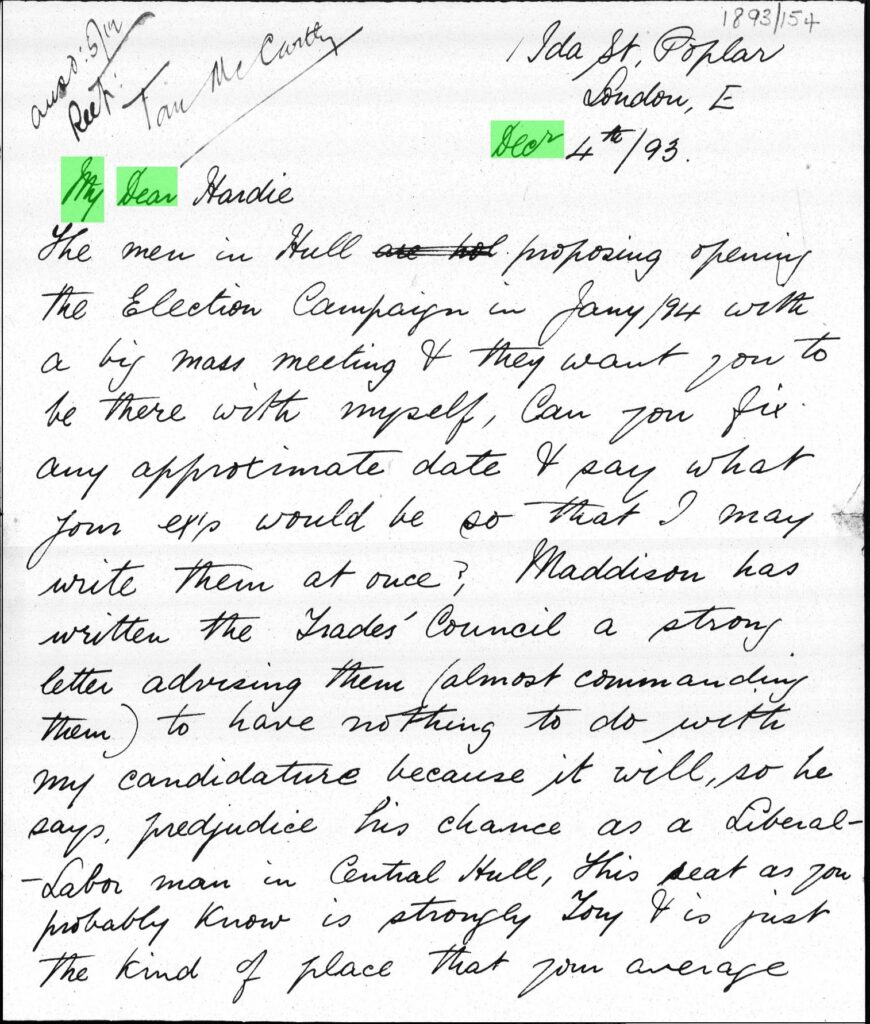

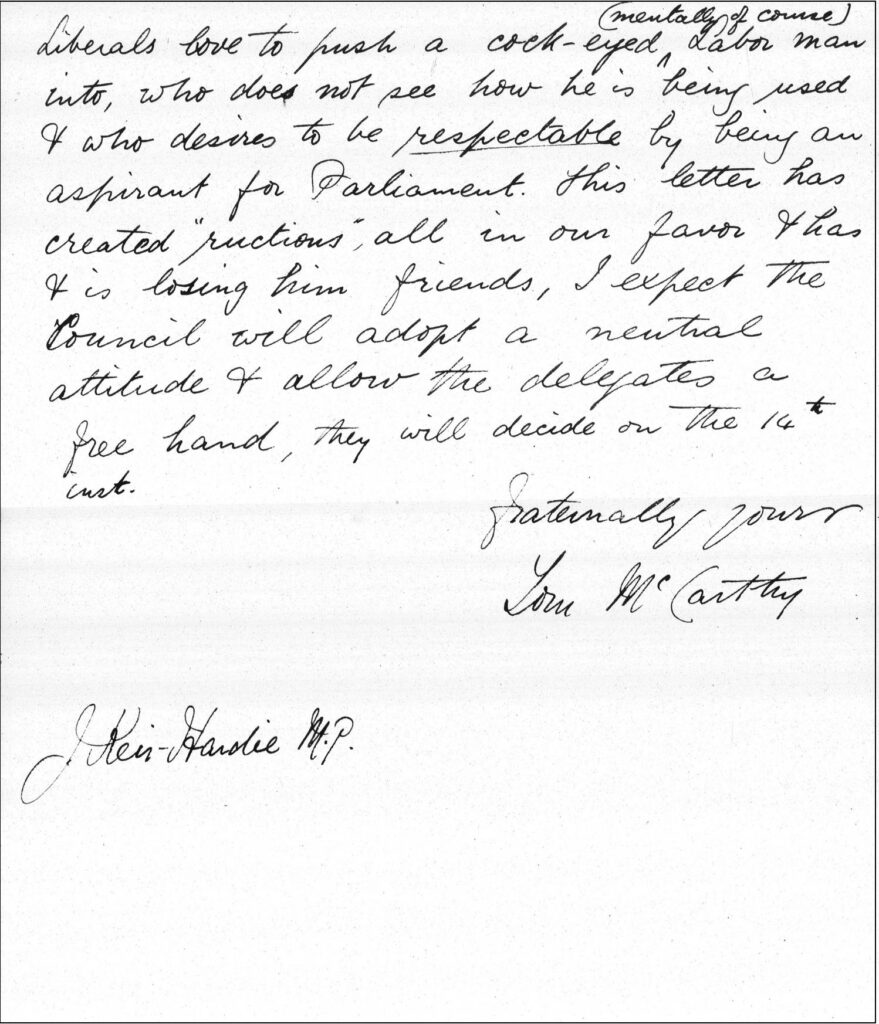

Personal bias is just that: personal. It’s not a culture or organization that enforces a particular viewpoint, and often is said without consideration or concern about trying to appear neutral. Even if personal bias is easy to detect, the way it’s biased may not be so easy—especially if it’s taken within the context of time and place. Understanding the specifics of their biases means the reader must take into account who was writing the source, who was their intended audience, and finally what were their limitations of knowledge on the subject. It’s rare that a private letter is written with the idea that anyone but the receiver is reading it, with more consideration than the writer’s current thoughts and feelings, often revealing opinions they wouldn’t reveal to the public—at least without couching it in more agreeable terms. For example, a letter written by trade unionist and founder of the Independent Labour Party (ILP), Thomas McCarthy, complained to a friend about the political situation in Hull, making rather unflattering remarks about Frederick Maddison. Personal bias can often give insight into actions specific people took in history, or legal/political decisions made by state and government.

(An 1893 private correspondence between Thomas McCarthy and a friend, remarking Frederick Maddison as a “cock-eyed (mentally, of course) Labor man” being used by Liberals to try to take a traditionally Tory seat, from Archives of the Independent Labour Party in Political Extremism and Radicalism, Part III.)

This personal bias is also what gets most researchers and academic writers into trouble, as they are often unaware of their own shortcomings, sometimes rejecting strong sources critical to their point of view due to these subconscious biases. Often, one should stop and ask themselves, “Am I rejecting this because it’s wrong or because I just don’t like what it’s saying?” So not only does the researcher have to be aware of the personal biases of their subjects, but also of their own.

Can my paper be bias-free? No, but here’s how to minimize it.

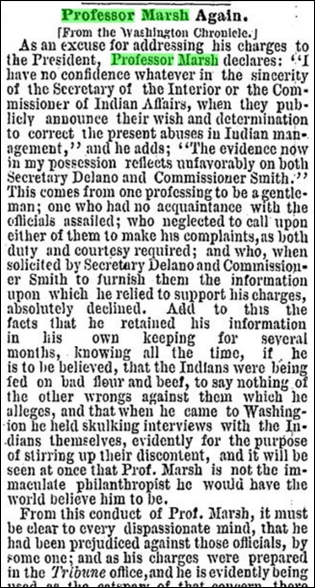

What does one do with a biased source? It depends on the exact nature of the bias, and the writer’s intended use in their academic or professional work. The first (and perhaps most important) step is deciding if there’s something worth using in a biased source. For example, a paper on racial bias in education could perhaps safely dismiss an opinion piece from a member of the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) as being without merit, given their history and specific racist ideologies, while a paper on Jim Crow laws may cite the KKK to show how their prejudices and use of terrorism helped to reinforce those laws.

The second step is acknowledging bias—even if it’s bias that one agrees with—citing specific points to try to maintain consistency in logic that’s required from all papers. Thirdly, one should pick their battles when it comes to the biased sources; sometimes a paper must argue against a biased source, so it’s important to find counterexamples to poke holes in flawed arguments. Other times, the specific bias in a source isn’t relevant to the paper’s topic and shouldn’t be given too much time or effort to refute, as it would distract from the paper’s focus. For example, if one is writing an academic paper on the Bone Wars (the fossil hunting rivalry between Edward Drinker Cope and Othniel Charles Marsh), addressing the biases between the two men and how the media portrayed their rivalry is relevant; what isn’t relevant is devoting excessive paragraphs to Marsh’s fight with the Bureau of Indian Affairs outside the context of his questionable permission to dig in Indigenous lands. Focusing on a biased account that’s not relevant to the document will not only cause a paper to lose its focus but will also unintentionally prejudice the reader for or against the subject.

(An article decrying Marsh’s agitation for better treatment of the Sioux as ungentlemanly—an example of a biased work that may not be relevant to a paper, from the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, July 24, 1875, in the Nineteenth Century U.S Newspapers archive.)

Conclusion: Face It, We’re Biased

Bias is everywhere, and may or may not have a conscious reason behind it. The best any human being can do is acknowledge their own shortcomings and be aware of how to spot them in the choice of media they consume. The facts are impartial, but how we perceive those facts is what can get us into trouble, as everyone has their own personal truth derived from their perceptions, upbringing, and ability to critically think about what they learn and feel about the world around them.

If you enjoyed reading about biases in primary sources, check out these posts:

- Find Unbiased Resources on U.S. Voting

- Two Impressive Reviews for Political Extremism & Radicalism in the Twentieth Century

- Why Study Regional and Local Newspapers?

Meet the Author

Brittany is a history major with a minor in museum studies at the University of Wyoming. She’s an avid reader and writes short fiction in her spare time. She’s been enjoying doing deep dives into the university’s archives during her internship.