| By Gale Staff |

Environmentalism is important to today’s university students. For some, campus sustainability initiatives factor into their overall enrollment decisions, and there’s been a significant increase in the number of environmental studies degrees awarded in the past few years. However, the sustainability field often highlights the same key figures, such as Rachel Carson, Henry David Thoreau, Jane Goodall, and Bill McKibben. Your students undoubtedly recognize names like Greta Thunberg or David Attenborough from popular media.

While their accomplishments are significant, the environmental studies playbook contains a cast of exceptionally diverse players. Ai Weiwei, from China, is a politically outspoken environmental activist and artist. Yolanda Kakabadse, from Ecuador, advocated for meaningful protection of endangered species while serving as president of the World Wildlife Fund. Winona LaDuke, a member of the Anishinaabe (or Ojibwe) Native American tribe, is a prominent indigenous land rights and climate change activist.

With help from Gale’s Environmental History: Colonial Policy and Global Development, 1896–1993, let’s focus on the life and contributions of Ralph Elwood Brock, the first Black forester in the United States. While a pioneer in the industry, Brock’s name remained in obscurity for most of the twentieth century. It wasn’t until the 1990s, when forestry historians found a captivating box of letters, ledgers, and notes detailing Brock’s life and research, that this prodigious figure received the credit he was due.

Study Brock’s Early Life

Born in the late nineteenth century in Pennsylvania, Ralph Brock would become a pioneer in the conservation movement and an accomplished scholar. He earned the distinction of being the first Black forester in the United States—a specially trained conservation professional who helps maintain forests and other vital ecosystems. During that period, few Black people had the opportunity to pursue the education required for this profession, making Brock’s achievements even more noteworthy.

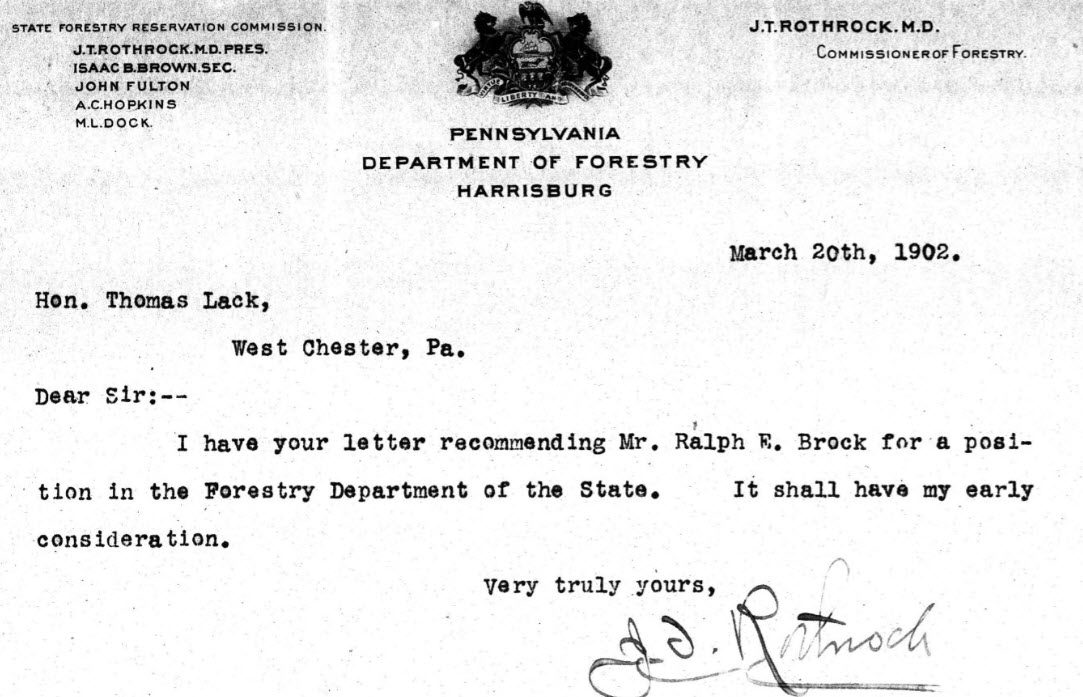

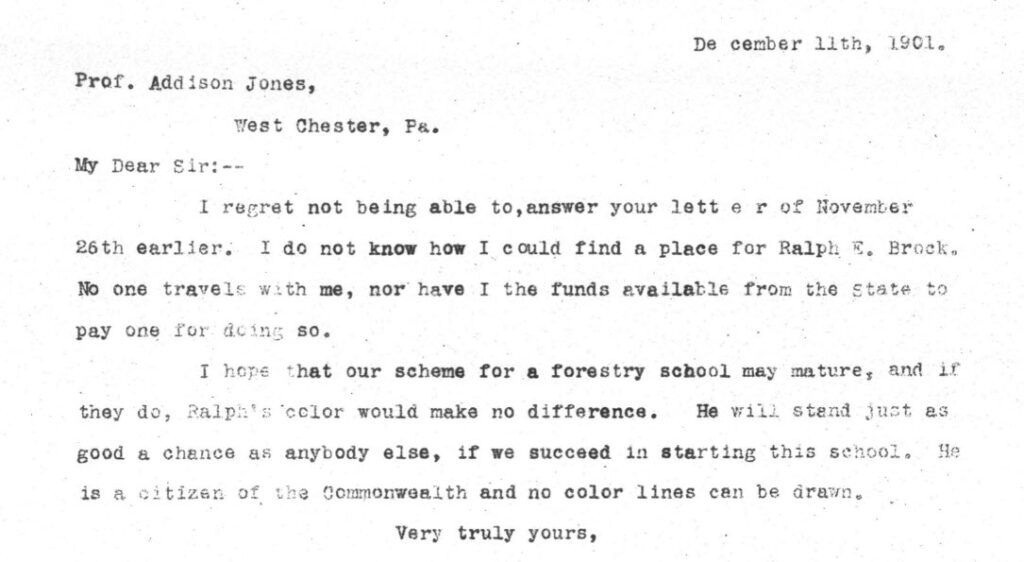

Brock’s home life was supportive, and his parents valued education. He was a standout student, and his school’s superintendent went so far as to personally recommend the young Brock to Joseph Trimble Rothrock, Pennsylvania’s forestry commissioner. The relationship between Brock and Rothrock gave the former a foot in the door. Rothrock was a mentor, as shown in this personal letter in which Brock requests book recommendations from the respected environmentalist. He also advocated for Brock, declaring, “He is a citizen of the Commonwealth, and no color lines can be drawn.”

Brock’s natural prowess earned him a coveted spot at Pennsylvania’s State Forest Academy, where he studied and trained in forestry and conservation from 1903 to 1906. After graduation, he remained at the institution, becoming superintendent of the Mont Alto Reserve nursery and committing himself to learning about forest preservation.

Learn About His Later Contributions

In 1911, Brock left his post at the State Forest Academy. While his exact motivations are uncertain, historians speculate that his departure could be related to the racism and disrespect he suffered from the institution’s white student body.

After that, Brock moved around, engaging as a private forester in Philadelphia and Cleveland. In 1928, John D. Rockefeller, Jr. employed Brock as a gardener for Harlem’s prestigious Paul Laurence Dunbar Apartments and the Radio City Gardens at Rockefeller Center.

Brock died in 1959 and was buried in his hometown of West Chester, Pennsylvania. He left an impressive legacy for the conservation movement—particularly regarding his role as superintendent at the academy’s nursery, which flourished under his care. Throughout his life, he was deeply dedicated to protecting and celebrating the natural environment.

Though modern research did not recognize his contributions for some time, his name and work have since been honored through state historical markers, an environmental stewardship scholarship fund, and even a display at the State Museum of Pennsylvania’s Ecology Hall. Brock spent his life preserving our natural environment despite the barriers and racism he faced; his story is a vital and inspirational piece of environmental history.

Explore More BIPOC Contributions to Environmentalism

Environmental History includes primary source information about often-overlooked individuals, like Ralph E. Brock, helping you bring attention to vital yet lesser-known facets of the sustainability movement. Brock’s story represents just one experience.

With Environmental History, you and your students can explore the lives of others like Brock, whose times and contributions need to be studied and shared. For example, scientist George Washington Carver (often incorrectly credited with inventing peanut butter), was fundamental to American agriculture—studying crop rotation, plant diversification, and healthy soil systems. He developed soil preservation methods and discovered how agriculture is inextricably linked to a healthy ecosystem.

Melody Starya Mobley was the first Black woman to serve in the U.S. Forest Service. After a lofty 45-year career in federal land management, she continues to advocate for conservation initiatives, climate justice, and DEI initiatives within the field of sustainability. Chief Randy Moore is the first Black man appointed chief of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Forest Service, managing millions of acres of national forest land. Chief Moore is a vocal advocate for racial equality, combatting climate change, and helping people connect to nature.

Embrace an Interdisciplinary Solution

Environmental History is a one-of-a-kind collection featuring primary source material related to various conservation issues and the evolving relationship between humans and the natural environment. Academic faculty will find value in these archives, whether through the lens of environmental studies, twentieth-century history, international studies, geography, anthropology, or sustainable development. You and your students can explore a range of environmental themes, unique global perspectives, and even quantitative historical data on climate change.

The complexities of our environmental problems demand a rich, interdisciplinary solution. After all, a healthy ecosystem requires heterogeneity to thrive. And teaching the history of conservationism provides a vital opportunity to uplift voices and stories traditionally left out of the mainstream.

However, a recent census shows less than three percent of foresters and conservation scientists are Black. That statistic is not surprising, considering environmental studies is one of the least diverse fields in STEM. Representation matters. Help inspire a new and more diverse generation of conservationists and highlight BIPOC contributions to the environmental movement.

Enhance your research with the voices and details housed in Environmental History: Colonial Policy and Global Development, 1896–1993, and inspire a more inclusive approach to solving big-picture environmental issues.

If your college or university is not an active Gale subscriber, contact your local sales representative to learn more and access a trial of our curated academic databases.