| By Gale Staff |

We all recognize George Washington—he’s on our money, our cities bear his name, and his likeness is even carved into a mountainside. But the version of Washington often presented to elementary students can feel oversimplified, reducing this fascinating historical figure to little more than a founding father with wooden teeth—a myth that doesn’t even hold up to historical fact!

In reality, George Washington was a sharp decision-maker with the remarkable ability to balance risk with reason. His role in shaping a new nation offers examples of innovative leadership and courage under pressure that can make history more exciting for the elementary classroom.

For our first president’s birthday, bring George Washington and the Founding Fathers to life with Gale in Context: Elementary, a dynamic resource that gives teachers all the tools they need to engage students with compelling, curriculum-aligned content.

Growing Up on Ferry Farm

George Washington grew up at Ferry Farm along the Rappahannock River in Virginia, where he spent his first decade living a comfortable life with his wealthy colonial family. However, his life changed dramatically when his father passed away, leaving George—then just 11 years old—with limited funds for a formal education.

Washington did not let this deter his ambition. He was aware of his educational shortcomings, so he dedicated himself to mastering the subjects and social skills he believed would elevate his prospects.

The future president borrowed books from neighbors and mentors to continue self-directed study in geometry and trigonometry. He also began learning practical trades, including surveying areas of land to create boundary maps.

Learning to Lead

Washington’s transition from surveying to military leadership began with his involvement in the French and Indian War (1754–63), during which the British and French fought for control of North American land.

Before the war’s start, Virginia governor Robert Dinwiddie asked Washington, then 21, to deliver a message to French forces in the Ohio Valley warning them to leave territory claimed by Britain. Washington’s appointment was practical: because of his prior surveying experience, Washington understood the terrain well.

The following year, Washington returned to the Ohio Valley with a small group of Virginia soldiers to confront the French. He led the construction of Fort Necessity, a hastily built stockade, but French and Native American forces soon surrounded it. After a day-long battle in July 1754, Washington was forced to surrender, marking the start of the war.

Over the next few years, Washington gained valuable military experience with the British force. However, he also questioned the British troop’s flawed approach to North American warfare.

Battle tactics like organized formations during open-field combat served their forces well in Europe. However, North America’s dense, woodland terrain was better suited to the French and Native Americans’ guerilla-style ambushes, which left British troops ill-prepared and vulnerable to surprise attacks.

Activity Idea: One strategy Washington learned during his military service was encoding messages, which he later used against the British during the Revolutionary War. Gale in Context: Elementary has a pre-made lesson plan for students to practice classic spy tactics, including making heat-sensitive ink and breaking a cipher.

Washington on the Path to Revolution

Washington’s journey from British subject to leader of the movement for independence was gradual, and largely influenced by policies the Crown imposed after the French and Indian War.

The first troubling policy was the Proclamation of 1763, which restricted westward colonial expansion. Tensions continued to rise with British laws like the Stamp Act (1765) and the Townshend Acts (1767) imposing taxes on everyday goods, angering colonists who felt unfairly taxed without representation in Parliament.

By 1769, Washington actively opposed the Crown and collaborated with George Mason to author the Fairfax Resolves. This document called for the colonies to unite in protest of British overreach by boycotting imports and drafting a plan to defend their fundamental rights.

Washington’s work on the Fairfax Resolves led to his serving in the Virginia House of Burgesses and being chosen as a delegate to the First Continental Congress in 1774. Here, he worked with other representatives from the colonies who had gathered to coordinate their response to British policies.

After the Battle of Lexington and Concord in April 1775, the colonies realized they needed a strong leader to organize their fight for independence. The Second Continental Congress chose George Washington as general of the newly formed Continental Army.

Activity Idea: Divide students into small groups and assign them key events leading up to the Revolutionary War, like the Stamp Act or the First Continental Congress. Ask each group to research their event using Gale In Context: Elementary and present it to the class in their own words.

Crossing the Delaware River

In the earliest days of the Revolutionary War, the Continental Army struggled to gain momentum against British forces. They suffered heavy losses at the Battle of Bunker Hill in June 1775 and a major defeat at the Battle of Long Island in August 1776. These early setbacks left morale low and the army desperate for a victory.

Although the odds were stacked against them, George Washington made a daring decision on Christmas night in 1776 that would become one of the defining moments of the Revolutionary War.

On the other side of the Delaware River from where Washington’s army was camped, the Hessians—German soldiers hired by the British—had an encampment in Trenton, New Jersey. The conditions were terrible, with freezing temperatures and icy waters making crossing dangerous. However, it was a chance to leverage the tactics Washington had learned during the French and Indian War to launch a surprise attack, using the rough North American terrain to his advantage.

The attack succeeded. After months of defeat, the Continental Army finally received the morale boost it needed, and the newly founded United States of America saw a glimmer of hope that Washington’s strategic boldness would turn the tides of the war.

Activity Idea: Show students Emanuel Leutze’s iconic Washington Crossing the Delaware and ask them to analyze what they see in the painting. What details stand out? How does the artist make Washington and his soldiers appear brave and determined?

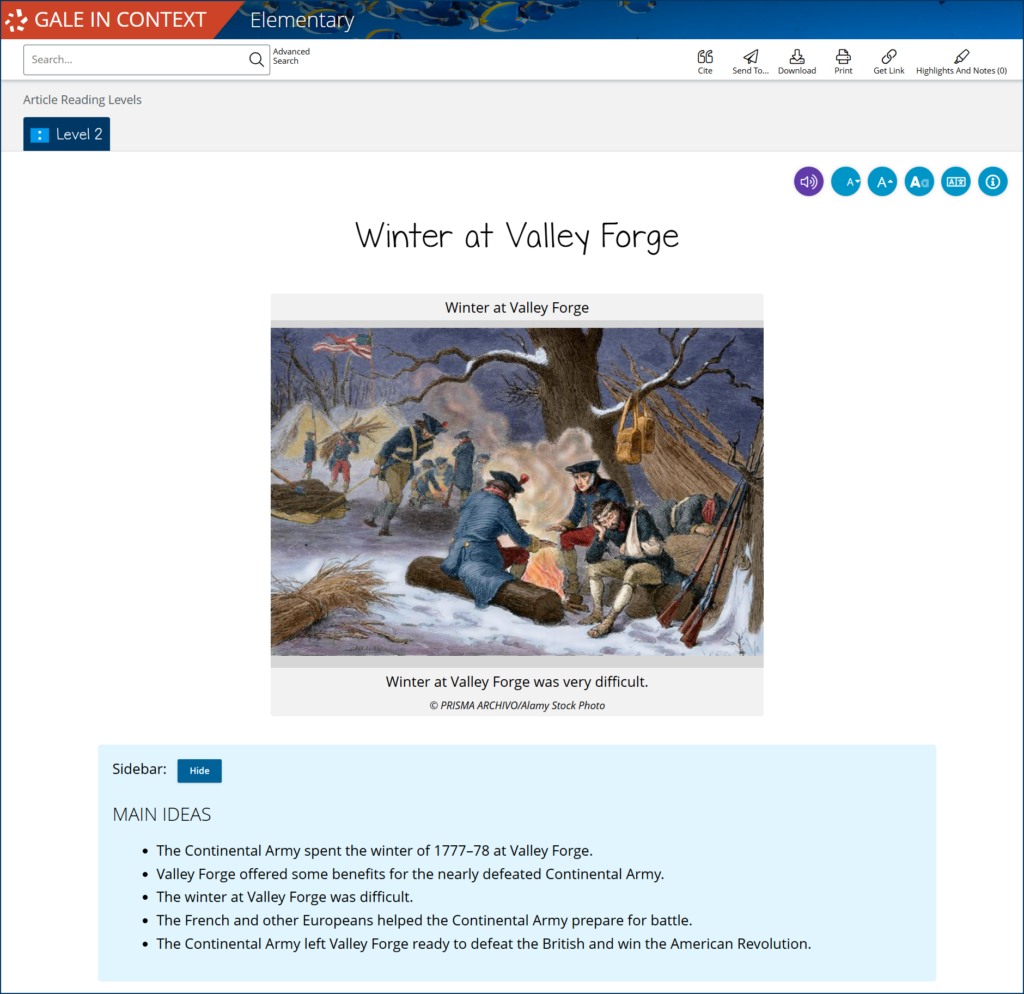

A Harsh But Strategic Winter at Valley Forge

The following winter, 1777–78, saw the Continental Army bunker at Valley Forge. There, Washington’s leadership was again tested when confronted with another deadly threat to America’s victory: disease.

Experts estimate that 90% of the Continental Army’s casualties were illness-related, with smallpox being the worst offender. Knowing its spread could cripple his army, Washington continued his controversial decision to inoculate soldiers, a process he had cautiously begun the previous year.

Though he knew the risks of inoculation, Washington leveraged their time at Valley Forge to enforce strict quarantine procedures. Once again, he demonstrated his expertise in taking calculated risks and prevented the disease from tipping the war in England’s favor.

Activity Idea: Guide students in using Gale In Context: Elementary to research early smallpox inoculation methods. After they have some background on the process, discuss why Washington’s choice was risky and why he decided to proceed regardless.

Becoming America’s First President

In 1781, the Continental Army won the Battle of Yorktown. With the help of French allies, Washington’s forces surrounded British General Cornwallis, forcing his surrender and effectively ending the Revolutionary War. The Treaty of Paris (1783) formally recognized American independence two years later.

Washington resigned from his role as general and returned to Mount Vernon to live a quieter life out of the public eye. Yet the fledgling United States faced an uphill battle establishing its democratic government, so the nation again turned to Washington, unanimously electing him as the first president in 1789.

During his two terms, Washington established principles that continue to guide the presidency today. He particularly focused on establishing governmental accountability through a balance of power.

To that end, he formed the first cabinet, which brought together many perspectives to make decisions that would impact the nation. Washington also oversaw the creation of the federal court system, a branch of government necessary for upholding America’s checks and balances.

Another of Washington’s beliefs was that a peaceful power transfer was a cornerstone of American democracy. So, even as the citizens rallied for his continued presidency, he set the precedent of stepping down after two terms and placing the reins in the hands of John Adams.

Activity Idea: Have students compare Washington’s wartime leadership to his presidential leadership. Create a Venn diagram to highlight the similarities and differences in how he approached each role.

February is a busy month for elementary classrooms, with celebrations like Black History Month, Valentine’s Day, and Presidents’ Day providing opportunities for high-interest, curriculum-aligned units.

Instead of sifting through countless websites to find the right teaching and learning materials for your elementary students, simplify lesson planning and give them a safe platform to express their curiosity about history, culture, and more.

Reach out to your Gale sales representative to request a free trial in time for the spring semester!