| By Gale Staff |

The U.S. Capitol riot on January 6, 2021, prompted by President Donald Trump after his loss in the 2020 presidential election, and the subsequent trials of President Trump’s supporters and right-wing militia group leaders accused of committing criminal activities, including those of rioters who committed violent attacks on Capitol police during the insurrection, have brought up a question many of us never had to consider: Has the Capitol been stormed before?

Though the Jan. 6 attack and insurrection by a pro-Trump mob on the Capitol building was a monumental moment in the history of the United States, it wasn’t the first time the Capitol building or the U.S. Senate were attacked in an act of violent protest or domestic terrorism. In the nineteenth and the twentieth centuries, there were several notable events during which the Capitol was bombed or invaded, resulting in injuries and fatalities.

The riot and insurrection at the U.S. Senate building brought up other questions: Besides the insurrection of the Southern states that occurred in the United States before and during the Civil War, have there been other attacks or insurrections against the federal government? Are there examples of successful riots that resulted in the removal of a local government? Why did the mob gather and how did the siege on the U.S. Capitol unfold? What are the long-term effects of this attack on American democracy? Could there be a threat of another insurrection or attack on the Capitol or even the White House?

Some of these questions, and more, can be answered in the popular Gale Primary Sources archive, Political Extremism and Radicalism. American history during the twentieth century was defined by a chain of events that brought about significant changes that transformed political ideologies in the United States. This archive helps historians and general researchers study the development, actions, and ideas behind political extremism during this pivotal time in history—up to today. Learn about such topics as the history of the president using the Insurrection Act against Americans, how left-wing militant groups like the Weather Underground (WUO) were formed, and why domestic terrorism cannot be ignored. Explore all seven subcollections of the archive here.

Learn about Previous Attacks

Opposition to the U.S. government is not unique to the events on Jan. 6. There have been several historic attacks on the U.S. Capitol since the building’s completion in 1800. One of the most damaging occurred in 1814 when the U.S. Capitol fell to a British attack during the War of 1812. British troops invaded Washington, D.C., and burned down the U.S. Capitol building. The Senate did not meet in the historic Old Senate Chamber of the building again until 1819. In 1915, Erich Muenter, a German-born former professor, blew up several sticks of dynamite on the Senate side of the Capitol. A Capitol police officer sitting nearby was uninjured, and the damage was minimal.

In the latter half of the twentieth century, security at the U.S. Capitol became a more ongoing concern after several breaches of security and threats to multiple members of the U.S. Senate occurred. Before 1954, people could walk into the visitor’s gallery overlooking the Senate chamber while congressmen were in session. Just like the White House, the U.S. Capitol is considered the peoples’ house, and the business of the federal government should be open to the people.

On March 1, 1954, four Puerto Rican nationalists attacked members of Congress who were gathered on the House floor for an upcoming vote. The four individuals—three men and one woman, Lolita Lebrón—who were part of the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party entered the visitor’s gallery above the chamber with handguns and opened fire, wounding five members of Congress: Alvin Bentley, Clifford Davis, George Fallon, Ben Jensen, and Kenneth Roberts.

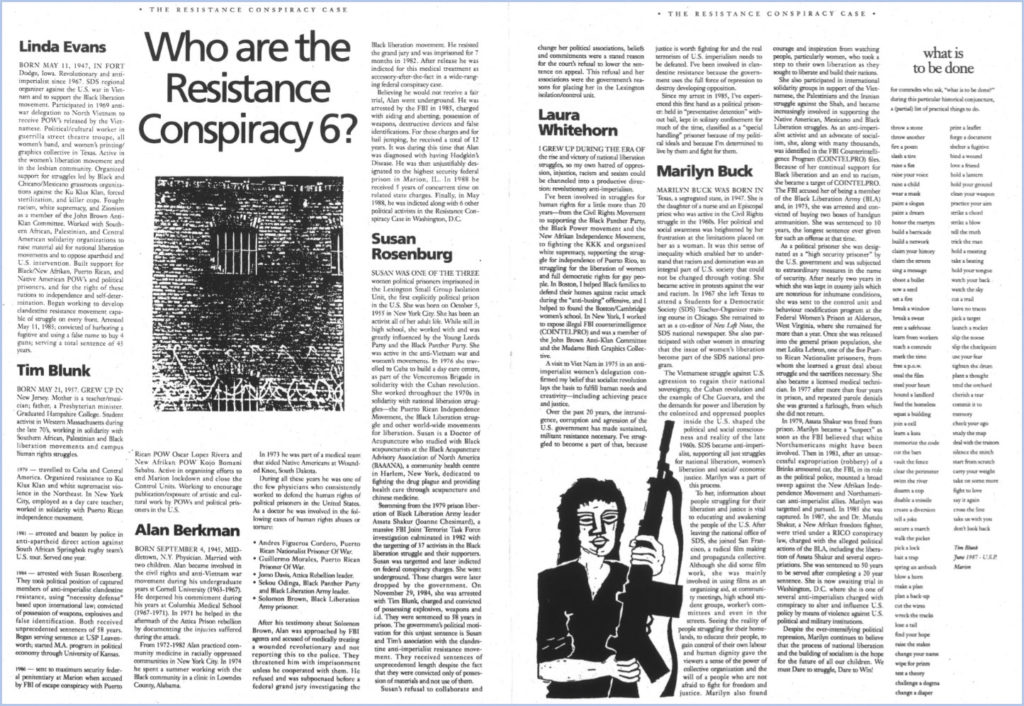

On November 7, 1983, far-left activists Laura Jane Whitehorn and Linda Evans placed a bomb in the U.S. Capitol that tore through the second floor Senate wing in an attempt to assassinate Republican Senators. No one was injured in the attack, but the bombing did cause more than $250,000 worth of damage. Known as part of the “Resistance Conspiracy 6,” Evans and Whitehorn were involved in struggles for human rights for a little more than 20 years, from the Civil Rights Movement to supporting the Black Panther Party and fighting against white supremacists, before they attacked the Capitol.

In a fatal attack on July 24, 1998, Russell Eugene Weston, Jr. stormed past a Capitol security checkpoint and killed two Capitol police officers. Weston exchanged gunfire with Capitol detective John Gibson who was protecting a congressman from the assailant. Both Gibson and Officer Jacob Chestnut died in the line of duty.

The Jan. 6 insurrection was planned and carried out by private U.S. citizens and far-right, armed militias loyal to Trump. The mob breached barricades and overwhelmed the Capitol police, wounding many in the violence. Hundreds of Trump supporters made it into the U.S. Capitol and searched for Congress members to stop the final count of votes to confirm President-elect Joe Biden. The rioters vandalized the Capitol and took the personal items of Congress members. One rioter was shot, and several Capitol police died later. It had been nearly 200 years since an attack on the Capitol like that of January 6 occurred outside of War.

During the 2016 election, Hillary Clinton’s verbal attack on her rival’s supporters as a “basket of deplorables” brought national attention to the disparate collection of largely anonymous digital activists and hatemongers known as the alt-right. This term was created in 2008 as a way to rebrand white nationalism and signal its difference from mainstream right-wing Republicans. Their infamous culture war turned into acts of violence, first in Charlottesville and then during the Capitol Insurrection. Now, more than one year later, we are continuing to assess what’s next for the alt-right. Will they successfully make the transition from a secretive, anonymous online community to a social movement with force in the real world? Or will they self-destruct in the process?

Continue Your Research with Primary Sources

When we discuss the storming of the Capitol on January 6, it’s helpful to understand the history and causes surrounding other acts of rebellion and revolt. Consider not only the history and “how” of each case, but also the motivation behind why these rioters committed their crimes and what they hoped to gain. The Political Extremism and Radicalism archive offers a close look into the thoughts and ideas of extreme political groups. Each collection in the archive includes rare monographs, newspaper articles, manuscripts, and firsthand accounts from extremist groups like the Puerto Rican Nationalist Party and Whitehorn’s WUO resistance.

To learn more about Gale Primary Sources and archives like Political Extremism and Radicalism, visit https://www.gale.com/primary-sources.