| By Gale Staff |

When Ridley Scott’s sci-fi horror Alien hit theaters in 1979, audiences were horrified by the dripping maws and reproductive process of the Xenomorph. However, the depiction of Ash, an android loyal to the Wayland-Yutani Corporation at the expense of the rest of the crew, truly sent a shiver down our spine.

Scott was undoubtedly ahead of his time and even ours. We don’t have uncannily human-looking machines posing as sleeper agent science officers, and the closest thing we have (for now) are android-esque machines like Sophia that still fall firmly in the “uncanny valley” camp. But, while AI in 2024 doesn’t look as frightening as depicted on screen, many people are still concerned that our endless array of techy toys and tools will soon go from making our lives a little easier to attempting to fully emulate human consciousness.

The artificial intelligence portal available through your Gale In Context: High School subscription gives your classroom unprecedented insights into a myriad of multimedia content that covers everything from the history of AI to the latest developments about its diverse applications.

Your students can dig into the life of Alan Turing, the father of theoretical computer science, reference texts explaining the ins and outs of machine learning, and editorial magazine articles that offer diverse perspectives on the topic, all from one intuitive, comprehensive database that makes finding resources a breeze.

Learn the Basics of How AI Works

There’s a misconception that AI “thinks” like humans do—spontaneously, creatively, and with context in mind. However, even the most advanced machine learning and natural language processing systems can’t replicate the flow and nuance of human speech.

Clear up the misconceptions and give your students a peek behind the curtain at this technology. Tools like DALL·E and ChatGPT still rely on humans, not only to create the algorithms needed to process complex data but also to provide the data in the first place.

While there’s considerably more complexity involved, here are the fundamental steps:

Programmers feed the AI software large amounts of text, images, or numerical data. The source of this data could be pretty much anything, from a business’s last 20 years of financial records to the billions worth of public web pages.

The AI uses an algorithm written by its creator to analyze the data for patterns—like what words are most likely to follow other words or various combinations of facial features used for image recognition.

Once the AI is done training, it can extrapolate its learning to new data sets, using its understanding of patterns to generate an output or prediction that falls within the parameters of its algorithm.

Students may be familiar with one example of AI’s presence in our daily lives: Spotify’s music recommendations, which offer similar tracks listeners might enjoy based on past listening data like genre, artist, lyrics, and technical features of music, such as the structure, beat, timbre, and dynamics.

Discussion Idea: One way that AI is affecting students is its use in standardized test essay grading, which University of Colorado professor Peter Foltz describes as “learn[ing] what’s considered good writing by analyzing essays graded by humans, and then they simply scan for those same features,” including things like the complexity of word choice, spelling, and grammar, and whether the writing is on topic.

Spark a discussion about the topic to evaluate how well students understand AI with these questions:

- What are the benefits of AI-graded essays? What are the downfalls?

- Are there aspects of essay grading that you think AI could do better than a human, and what are they? What about the other way around? Are there some parts of essay grading that only a human is capable of?

- How would it make you feel to know that an AI program is reading their essay rather than a human?

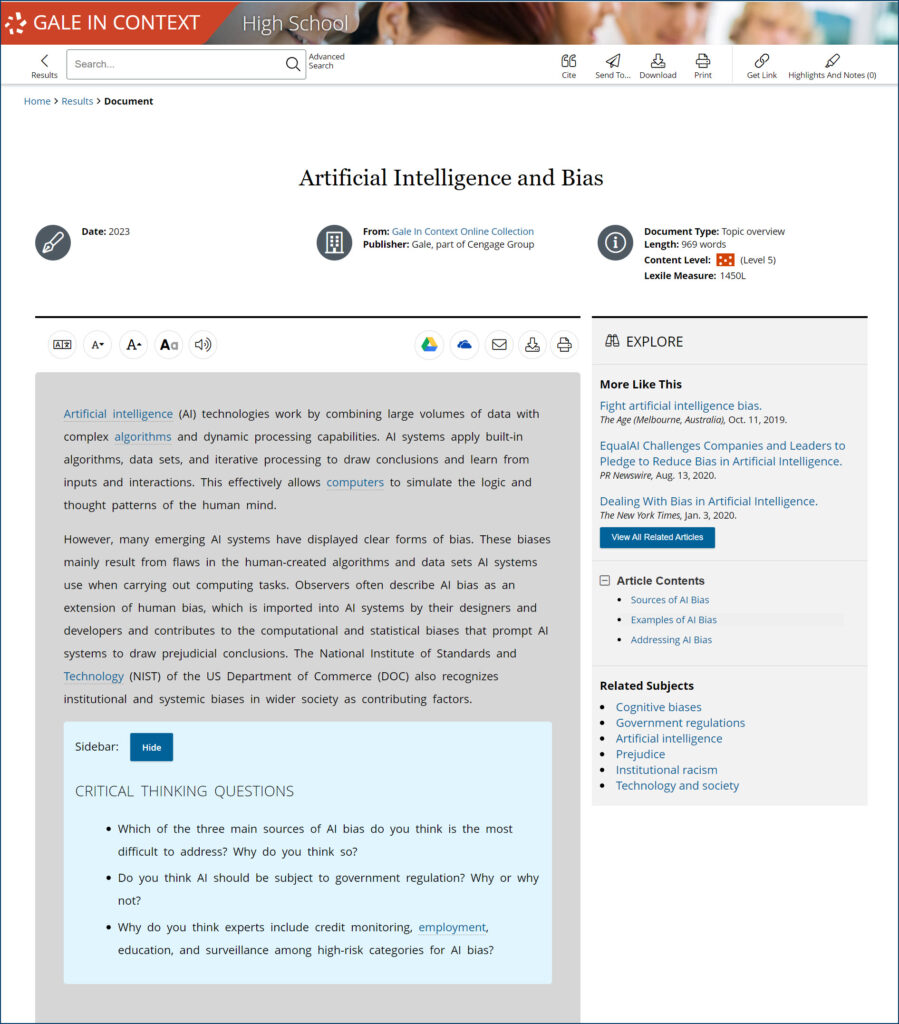

Recognize Biases in AI Algorithms

As discussed above, AI uses existing, human-created information to generate content that follows recognized patterns within a dataset. While that makes these programs good at creating logical outputs that replicate human logic, they also tend to perpetuate existing biases found in their training data.

A 2020 study showed the potentially harmful implications of replicating human behavior. Data sets from the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS) indicate that Black patients in U.S. emergency rooms tended to receive lower doses of pain medication compared to patients of other races. An AI system that uses these kinds of data sets to make decisions about pain medication dosage would perpetuate that human bias without the awareness necessary to recognize it.

Trends indicate that our students will soon face a world that relies on AI to make an increasing number of decisions. Take, for example, online loan applications, which are increasingly using points of so-called “alternative data” to determine creditworthiness. Examples include SAT scores, store purchases, where you go during the day, and when you go to bed at night.

Even your habits at the gas pump—specifically whether you go inside to pay or not—can be used to either approve or deny a loan. In an interview with NPR’s All Things Considered, Jo Ann Barefoot, CEO and Co-founder of the Alliance for Innovative Regulation, explained, “People who pay inside are more likely to be smokers. And smoking, supposedly, is more highly correlated with lack of creditworthiness.”

Companies testing out AI creditworthiness models argue that it’s a more equitable way to determine whether someone is qualified for a loan. The algorithm could calculate risk without requiring a FICO score, which overwhelmingly disqualifies younger borrowers with little credit history, and people from foreign countries where FICO scores don’t exist. However, there are glaring issues regarding AI’s tendency to confuse correlation with causation.

Paying inside doesn’t cause someone to be a smoker, and being a smoker doesn’t cause someone to have poor spending habits. However, because the data in the set indicated that pattern, an AI program can eliminate qualified borrowers from getting a loan just because they grab a coffee from their local gas station before work twice a week.

Discussion Idea: Gale In Context: High School has many resources that include questions to engage students in conversations. Ask learners to read the “Artificial Intelligence and Bias” topic overview page, then discuss these critical questions:

- Which of the three main sources of AI bias—human biases, systemic biases, or computational and statistical biases—do you think is the most difficult to address? Why?

- Do you think AI should be subject to government regulation? Why or why not?

- Why do you think experts include credit monitoring, employment, education, and surveillance among high-risk categories for AI bias?

Consider the Ethical Implications

This generation of high schoolers has grown up with this technology at their fingertips, so they’re already comfortable engaging with and stretching the limits of AI. As the saying goes, “With great power comes great responsibility,” which means using artificial intelligence with integrity and ethics in mind.

First, we have to consider the source of generative AI data.

ChatGPT is perhaps the most well-known example of the ambiguity surrounding the ethical use of AI after The New York Times sued OpenAI and Microsoft for using their copyrighted materials in their training dataset. While the defendant claimed fair use under the argument that ChatGPT is using the material to create something new and transformative, the Times lawyers said it’s being used to “create products that substitute for The Times and steal audiences away from it.”

Similarly, photo-generative AI scrapes massive amounts of image data, including artistic works, and uses them to create content. These machine-generated images are competition for those in creative industries, posing a significant threat to their earning capacity and using their own art to do it.

Another serious concern is the use of AI to create deep fake content, which Gale In Context’s topic overview of the subject defines as “videos as well as images, audio, and written messages that are digitally altered to combine and manipulate images and/or sounds. The resulting videos, sound clips, and messages make it appear that a person said or did something that they did not.”

There are legitimate use cases for so-called “synthetic media,” such as the Dali Lives experience, which brought a modern-day depiction of artist Salvador Dali to life on interactive screens and face-swap technology that allowed the late Paul Walker to finish filming Fast & Furious 7 after his death.

However, there are far more examples of these digital duplicates being used for nefarious purposes or, at the very least, that distort reality.

In 2023, Adobe Stock was inundated with thousands of AI photos—with the site’s permission—that depicted seemingly real-world events that never happened. Amongst them were supposed depictions of Black Lives Matter protests and explosions in Gaza, some of which were then picked up for use.

Similarly, there are examples of synthetic media in which politicians and celebrities appear to be involved in illegal, unsavory, or embarrassing situations that are entirely fabricated. In 2019, a video of Nancy Pelosi went viral on X (then Twitter) as she drunkenly slurred through a speech. It seemed convincing enough that other politicians retweeted it when the truth of the matter was that the video was an example of deep-fake content.

Discussion Idea: Legislation around AI is still in progress, but it’s increasingly relevant to high schoolers as new technologies and regulations around AI emerge. It’s essential that they learn to work with these tools in a way that respects others. You can prompt critical thinking with these questions:

- Who should be the legal owner of work generated through AI? Is it the programmer who created the algorithm behind AI programs like DALL·E, the user who inputs the prompt, or the person being depicted in the media?

- People and programs are getting better at creating deep fakes. How should lawmakers balance creative freedom with preventing the harm that can come from these types of media? Should there be consequences for those who create deep fakes that result in harm?

- What are some of the positive implications of synthetic media, both publicly and personally?

There are still many questions and considerations about the future of AI—but one thing we know for sure is that it’s only going to grow from here. Educators can help prepare students for an AI-driven future by teaching them that these technologies cannot be a substitute for human innovation and creativity. Instead, they should view AI as a supplementary tool to support their learning that must be used ethically and mindfully.

When you’re ready to bring artificial intelligence literacy skills into your classroom, turn to Gale In Context: High School for inspiration and information.

Not a Gale In Context: High School subscriber? Contact your local rep today for more information!