This summer, The Times Digital Archive is expanding its reach with the addition of five years of new content (2020–24), adding to a collection that already spans more than two centuries of reporting dating back to 1785.

The archive’s built-in tools include robust search functions to help users analyze the language of reporting and investigate claims with the ability to quickly zoom in and out of specific events. These search functions include tools like Term Frequency and Topic Finder, which make it easier to identify trends and connect related coverage across decades. All articles, headlines, and images are fully searchable, allowing users to cluster related ideas and identify and map trends using powerful visuals.

Let’s revisit a series of July headlines to see how The Times Digital Archive supports interdisciplinary work in history, political science, media studies, and rhetoric—all of which rely on source material and the ability to interrogate it at scale.

1799: The Discovery of the Rosetta Stone

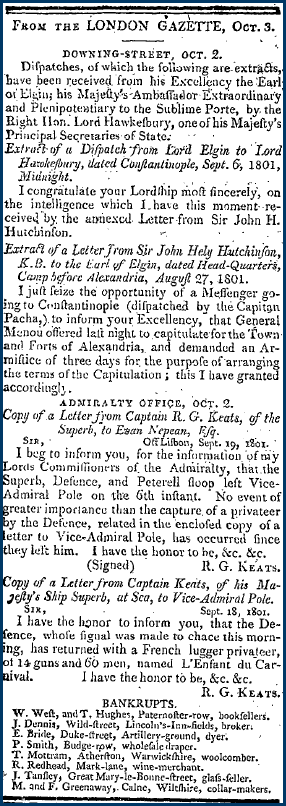

On July 19, 1799, during Napoleon’s campaign in Egypt, French soldiers unearthed the Rosetta Stone. But in 1802, it arrived in London—not Paris. After the surrender of French troops in 1801, the artifact was seized under the terms of the Capitulation of Alexandria, an agreement that transferred French-collected antiquities to British control.

Although discovered in July 1799, the first mention of the Rosetta Stone appeared in a short shipping notice three years later, listing it alongside embalmed animals, Arabic manuscripts, and carved statuary. The notice described “the stone found at Rosetta, in Lower Egypt” as being “of the highest consequence to the science of the antiquary, as it contains three different inscriptions—one in hieroglyphics, another in the vulgar Egyptian character, and a third in the Greek language.”

The Times did not refer to it as the Rosetta Stone until 1829—and only in the 1830s and 1840s did the object begin to appear regularly in coverage of museum exhibitions. An 1839 article describes the continued impact of the stone’s discovery 40 years later, calling it the “enlightening sun of Egyptian literature” for its role in helping to decipher Egyptian scripts.

Over the next two centuries, The Times tracked the stone’s evolving public role from field discovery to national trophy to symbol of contested heritage. Students can follow that trajectory using the Term Frequency tool to identify when terms like “Rosetta Stone” appeared more often and why.

Key Moments

- 1822: Champollion announces his decipherment of Egyptian hieroglyphs using the Rosetta Stone.

- 1922: Howard Carter’s discovery of Tutankhamun’s tomb sparks renewed Egyptomania and press interest in hieroglyphics.

- 2018: Renewed public debate over the Rosetta Stone’s ownership, including calls for its return to Egypt, appear in The Times amid broader discussions about repatriating cultural artifacts held in British institutions.

1937: Amelia Earhart’s Disappearance Tracked in Real Time

Starting on June 2, 1937—the day after she embarked from Miami on her second attempt at an around-the-world trip—The Times followed Amelia Earhart’s final flight with near-daily updates.

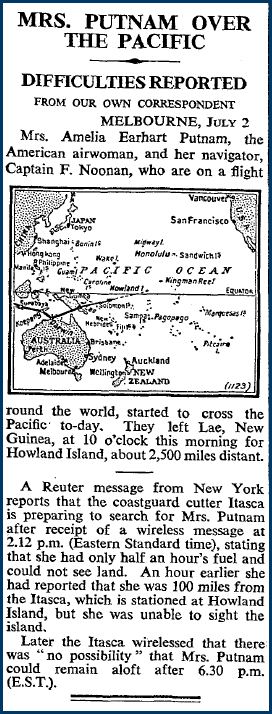

On July 2, the paper ran a prominent story titled “Mrs. Putnam Over the Pacific,” reporting that Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, had departed Lae, New Guinea, en route to Howland Island. The article described mounting concern from the US Coast Guard, noting that Earhart had radioed she was low on fuel and unable to see the island, adding that there was “no possibility” she could remain aloft after 6:30 p.m. Eastern time.

From there, coverage intensified into a rapid-fire sequence of daily dispatches with headlines logging the expanding search effort, from aircraft sorties to shifting grid maps relayed by the US Navy.

- July 5: “Mrs. Putnam Down in Pacific”

- July 7: “No Trace of Mrs. Putnam”

- July 8: “Putnam Search in New Area”

- July 10: “Search in New Area for Mrs. Putnam”

- July 12: “Seaplanes’ Search for Mrs. Putnam”

- July 14: “60 Aircraft to Search for Mrs. Putnam”

- July 19: “No Trace of Mrs. Putnam”

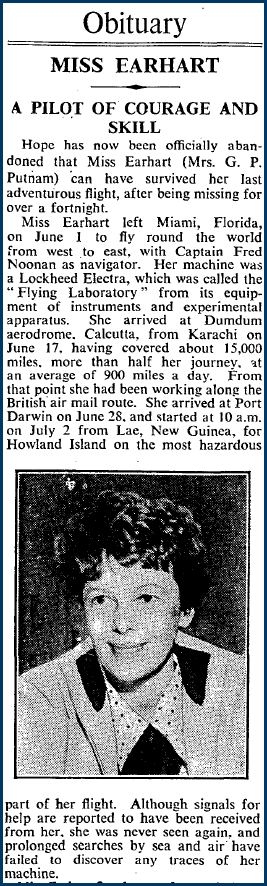

On July 20, after more than two weeks without new developments, the paper published a short obituary under the headline “Miss Earhart.” Although Earhart had not been found and no official declaration had been made, the obituary likely reflected a broader public assumption that she could not have survived, combined with an editorial decision to close the narrative.

While the obituary used her preferred professional name, Earhart, by which she is universally known and renowned today, The Times’ prior coverage had consistently referred to her as Mrs. Putnam, despite her rejection of its public use. In 1932, Earhart had written to The New York Times requesting that she not be referred to by her married name: “After all . . . I believe flyers should be permitted the same privileges as writers or actresses.”

Her obituary is rich with language that invites critical analysis. It notes her role aboard the Friendship in 1928, when she became the first woman to cross the Atlantic by air—but questions whether “sitting in an aeroplane as a passenger can be called a feat.”

For historians, looking back through The Times’ archives can help us better understand the cultural environment in which Earhart operated. On the same page as Earhart’s obituary and throughout the paper, ads depict women not as adventurers or professionals, but as elegant consumers. Another cartoonish ad extols the joys of cigarettes, with Lady Semolina Rhys Custard, a fictional socialite, crediting her energy and charm to Greys. Together, these ads reinforce a narrow vision of femininity rooted in appearance and aristocratic whimsy, an image that is worlds apart from Earhart.

Full-page access allows students and scholars to consider these juxtapositions as rich materials for how gender roles were reinforced from a variety of angles.

July 1953: The Korean Armistice and Cold War Logic of Containment

The Korean War began in 1950, when North Korea advanced south to unify the peninsula under communist control. The United States viewed the invasion as a direct challenge to the postwar order and intervened under a United Nations command. China later entered the war on North Korea’s behalf, pushing US and South Korean forces back toward the middle of the peninsula. What began as a regional conflict quickly became a proxy war between Cold War superpowers.

By mid-1953, the war had dragged on for three brutal years. The front lines had largely stabilized near the 38th parallel, and negotiations over issues like prisoner repatriation and the recognition of opposing regimes had stalled. Both sides had exhausted what they could achieve militarily without risking broader escalation, yet neither was willing to concede. The result was a prolonged stalemate, held in place by the growing risk of nuclear war. All sides understood the consequences of pushing further. The armistice signed on July 27, 1953, was a military compromise between the United Nations Command, the Korean People’s Army, and the Chinese People’s Volunteer Army.

South Korea refused to sign. President Syngman Rhee opposed any agreement that left the country divided—but the deal proceeded without him. Still, it demonstrated that Cold War powers could tolerate unresolved conflict. Although an uneasy equilibrium was maintained, the threat of renewed war became a defining feature of Cold War crisis management.

Because the Korean War ended in a stalemate rather than a resolution, it left behind a long trail of diplomatic tension and military posturing well beyond the events of 1953.

Researchers examining the Korean War’s legacy can use the Topic Finder tool in The Times Digital Archive to surface decades of related coverage. Topic Finder is a standalone visualization tool that analyzes the top results from your query by extracting keywords from each article’s title, subject terms, and introductory text. It then groups these frequently occurring terms into clusters, displayed as tiles or a wheel, revealing recurring themes and associations.

For example, selecting the Korean Foreign Relations tile highlights decades of failed diplomacy and recurring negotiations between North and South Korea. Some articles, like “North Korea Offer of Unity” (1970) and “Koreans Agree to Fresh Peace Talks” (1997), reflect repeated attempts to renegotiate or replace the original armistice. Others—such as “US Missile Warning Carries Threat of New Korean War” (1993)—betray the fact that tensions were still running high despite those efforts.

Clustering articles in this way helps researchers work more efficiently, as there’s no need to run separate searches for every variation on keywords about armistice diplomacy. Instead, Topic Finder presents them in tidy groups that make it easier to identify patterns and find the high-quality archival content they need to continue their scholarship.

1969: Bringing the Apollo 11 Launch Into the Living Room

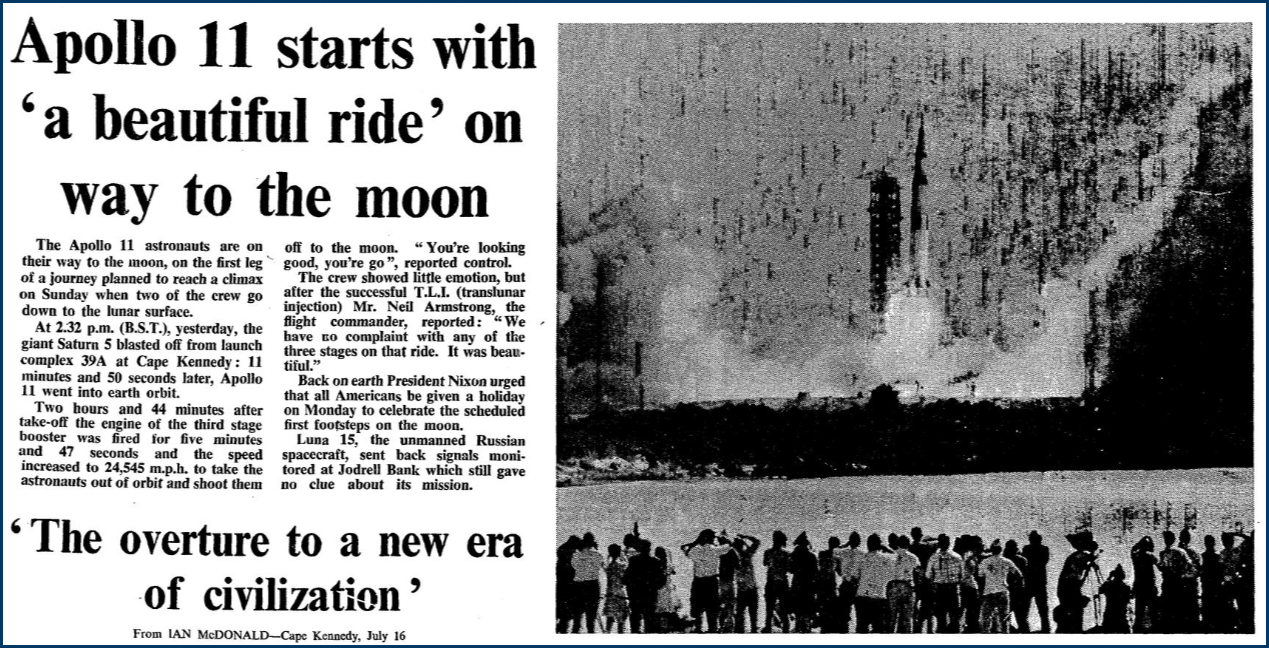

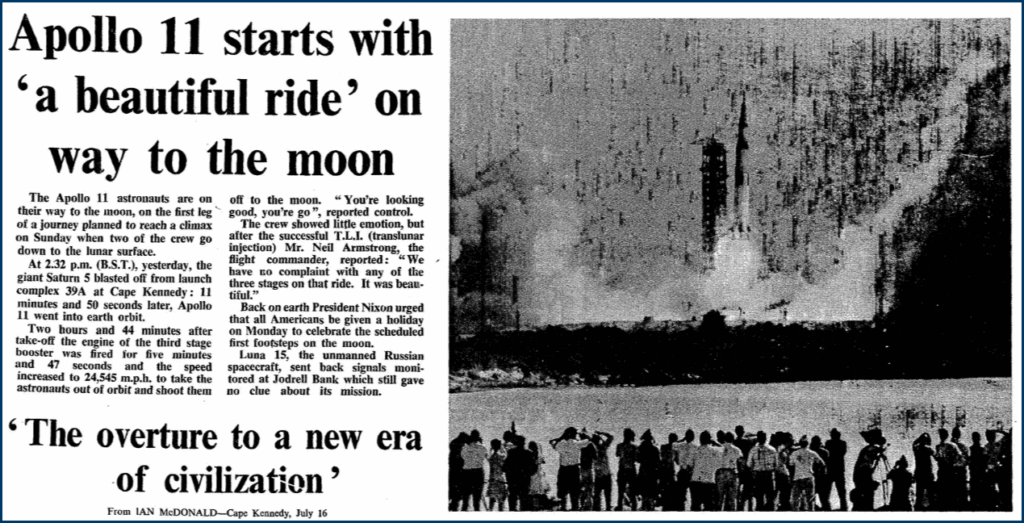

During the week of Apollo 11’s launch on July 16, 1969, The Times took on a challenging editorial task: explaining one of the most complex technological missions in history in terms the general public could understand. The July 16 edition described the paper’s coverage as a “guide for your armchair,” setting up readers to track the spacecraft’s progress from launch to the planned touchdown on the Moon’s surface.

In “Flightplan” The Times mapped each mission stage from liftoff and lunar orbit to extra-vehicular activity (EVA), re-docking, and return. The news team separated technical acronyms into a visual sidebar, making NASA’s specialized vocabulary legible to civilian readers. Adjacent coverage explained the Apollo space suit, a 16-layer garment designed to withstand the vacuum and temperature extremes of the lunar environment, including an internal cooling system, a pressurized shell, a life-support backpack, and approximately $300,000 in equipment they would jettison before re-entering the ship.

On July 19—just ahead of the scheduled landing—the paper published “Moonday” offering a timeline of how the astronauts would spend approximately 21 hours collecting samples and data. Two days later, “Man Takes First Steps on the Moon” recapped the details of the moonwalk transmission and how Armstrong and Aldrin maneuvered during EVA. The coverage of July 22 carried the narrative forward, preserving the entire transcript during the men’s time on Tranquility Base, “‘a stark but beautiful’ boulder-strewn wasteland on the right-hand side of the moon.”

The Times devoted a significant amount of effort to explaining the Apollo 11 mission. Through diagrams, sidebars, and plain-language reporting, the paper helped readers mentally reconstruct a complex event. That level of editorial care reflected both the historical weight of the moment and the public’s eagerness to understand it.

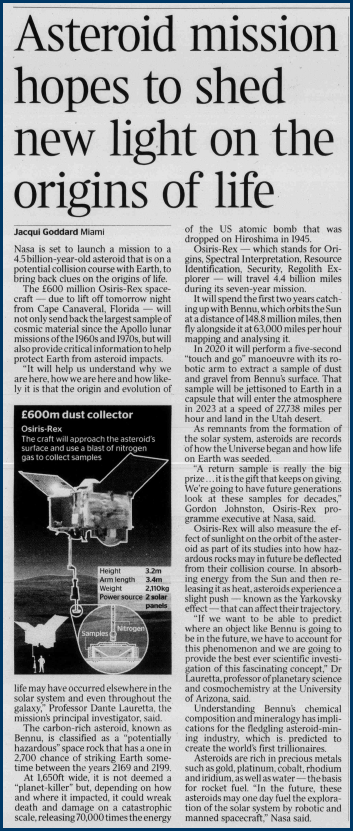

In the decades that followed, that enthusiasm waned even as pioneering missions continued. A 1980 satellite launch—marking an early milestone in India’s space program—appeared only as a short item in a news roundup, while a 2016 asteroid mission probing the origins of life was tucked deep inside the paper on page 19 and largely stripped of visuals or contextual support. Comparing these moments reveals not just how reporting styles changed, but how public interest and editorial priorities evolved with them.

With The Times Digital Archive, researchers can investigate how evolving coverage reflects the state of public imagination and the editorial choices that shape our collective memory of scientific progress.

Across more than 12 million digitized pages, The Times Digital Archive gives researchers access to one of the most extensive runs of historical journalism available. Advanced search tools—like Topic Finder and date filtering—empower users to hone in on the content most relevant to their work across disciplines and investigative pathways. To learn how the archive can support instruction and research across your campus, contact your Gale representative for more information.