For those of you who saw Downton Abbey last season, you saw Rose bringing a jazz band (with lead singer Jack Ross) to Downton, shocking many not only because of Jack’s race, but also the music itself.

I actually knew very little about jazz prior to writing this post. The Downton Abbey episode intrigued me, and I was eager to learn more. Luckily, I work at Gale and have access to several very excellent resources that have allowed me to do the research.

I am familiar with the sound as well as some tidbits regarding its leading musicians like Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong, but I was not aware jazz has a rather long tradition, dating prior to this particular Downton Abbey episode, with most sources citing New Orleans as its birthplace in the late nineteenth century.

After doing some searching in GVRL, my interest was piqued. The entries I read on jazz all mentioned Louis Armstrong’s contributions (as they should), so I bopped over to Biography in Context to learn more. Born in 1901 (after the birth of jazz), Louis Armstrong was born into abject poverty. He worked as a child until, at the age of 12, he was sent to the Colored Waif’s Home as a juvenile delinquent. Interestingly enough, this wasn’t his first time sent to the Colored Waif’s Home. A recent discovery of some documents from the Home cite an earlier run-in with the law, in 1910, when he was only nine years old.

Rather than letting his poverty define him or his trouble with the law, Louis Armstrong learned how to play cornet in the Home’s band, listened intently (and learned) from leading jazz artists in his teens, and played in several bands as he came into adulthood. By the time 1930 rolled around, Louis Armstrong was famous and toured all over the United States and Europe.

Anxious to see how he was portrayed in the newspapers of the time, I took a look in Gale NewsVault. Leading U.K. newspapers interestingly enough do not mention him in any detail. They mention people imitating (or mocking) him in other acts, but not much in the way of praise for his talented performances. The Illustrated London News, for example, only mentions him as a butt of a performer’s joke. The Times (London) mentions his appearances in the 1930s at various theatres, but not much outside of that. It really isn’t until the 1950s that the press decides to cover him in more detail. And interestingly enough, that is when he started to become one of the most beloved musicians and entertainers in the world, and in fact toured extensively on behalf of the U.S. Department of State, receiving an enthusiastic response wherever he went, even though the military was in turmoil over segregation and desegregation.

Anxious to see how he was portrayed in the newspapers of the time, I took a look in Gale NewsVault. Leading U.K. newspapers interestingly enough do not mention him in any detail. They mention people imitating (or mocking) him in other acts, but not much in the way of praise for his talented performances. The Illustrated London News, for example, only mentions him as a butt of a performer’s joke. The Times (London) mentions his appearances in the 1930s at various theatres, but not much outside of that. It really isn’t until the 1950s that the press decides to cover him in more detail. And interestingly enough, that is when he started to become one of the most beloved musicians and entertainers in the world, and in fact toured extensively on behalf of the U.S. Department of State, receiving an enthusiastic response wherever he went, even though the military was in turmoil over segregation and desegregation.

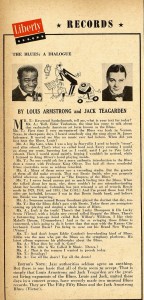

I did find this great piece from Liberty Historical Archive that features an interview, which provides a brief insight into Armstrong’s childhood; he talks about “hustling ‘stone’ coal after school” along a route until he’d get to Pete Lala’s cabaret where he’d stand inconspicuously outside while he listened to King Oliver’s band.

I did find this great piece from Liberty Historical Archive that features an interview, which provides a brief insight into Armstrong’s childhood; he talks about “hustling ‘stone’ coal after school” along a route until he’d get to Pete Lala’s cabaret where he’d stand inconspicuously outside while he listened to King Oliver’s band.

One interesting article from the BBC’s The Listener had little praise for Armstrong and preferred Duke Ellington by far, “The first time I heard Louis Armstrong’s records I was fascinated by the virtuosity of the frills he put round the tune; but after a few hearings I soon became bored by the monotony of the harmonic framework underneath.”

Do the newspapers of the time represent a similar attitude to what I watched on Downton Abbey towards a black man’s success and a music genre very different than what they are used to? Is it similar to how the Crawley’s and Grantham’s react to Jack Ross’ appearance? There seems acknowledgement that he exists, but very little deliberate attention.

Be that so, a man, who comes from almost nothing, excepting his exceptional skill and motivation is truly inspiring. It is good to know that his legacy has survived despite the lack of press at the beginning of his career. Taking a look at Armstrong’s life and success leads us to consider that there is more in us than we sometimes believe, and thankfully both Armstrong and others recognized what he had to offer as he developed into quite possibly the most recognized name in jazz’s history. Armstrong’s contributions to the history of music in the United States are unmatched.

1. “Blues and Jazz.” The African American Almanac. Ed. Christopher A. Brooks. 11th ed. Detroit: Gale, 2011. 1173-1242. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 2 Feb. 2015.

2. “Jazz.” Black American Biographies: The Journey of Achievement. Ed. Jeff Wallenfeldt. New York: Britannica Educational Publishing with Rosen Educational Services, 2011. 214-251. African American History and Culture. Gale Virtual Reference Library. Web. 2 Feb. 2015.

3. Grimes, William. “Documents Shed Light on Armstrong’s Youth.” New York Times 23 Dec. 2014: C2(L). Biography in Context. Web. 2 Feb. 2015.

4. “The Playhouses.” Illustrated London News [London, England] 23 Sept. 1933: 484. Illustrated London News. Web. 2 Feb. 2015.

5. Armstrong, Louis, and Jack Teagarden. “Records.” Liberty Magazine [Rye, New York] [1 Jan. 1948]: 52. Liberty Magazine Historical Archive. Web. 2 Feb. 2015.

6. Lambert, Constant. “Modern Dance Music.” Listener [London, England] 29 Apr. 1936: 844+. The Listener Historical Archive. Web. 2 Feb. 2015.

[alert-info]

About the Author

About the Author

Jennifer loves her children, dogs, and Jane Austen. She has a B.A. in English and Sociology from the University of Michigan, and spends her waking hours as a marketing director and feeding her family.

[/alert-info]Air Jordan