| By Ryan Price |

“As to the riding qualities of the Jeep, a chiropractor should be standard for each car.”

— Charles “Harry” Payne

The Jeep is as ubiquitous as America itself. It has been to battle, to camp, to the highest mountain and the lowest valley. It is a car fit for danger, adventure, and any rough road in between. In a story written by Colonel William F. Lee, the officer in charge of new developments for the U.S. Army—and specifically, the development of the Jeep for World War II—it was described this way:

“It’s a quarter-ton runt with a mechanical heart and a steel constitution; it has more speed than a backfield full of All-Americans; it can climb mountains; it can fly; it can swim; it can jitterbug across rough terrain at 50 miles an hour, hauling four armed soldiers and a 37 min gun with the same ease a hound dog carries fleas, and it is the first silk stockingless subject to enter a conversation whenever two or more Army men get together.”

Vehicles have been militarized since their invention, and although Spyker made great strides in 1903 and the Jeffery Quad during World War I, it wasn’t until 1935 that Walter Marmon and Arthur Herrington proved that four-wheel-drive vehicles—specifically two-wheel-drive Ford light trucks converted to four-wheel drive—could indeed be versatile and useful on (and off) the battlefield. The U.S. Army wasn’t quite satisfied, as it wasn’t with other models—specifically the Howie Carrier, which required the two occupants to lie prone on their stomachs behind a gun.

It was long in coming, as the Army rank and file had complained about the desire and benefits of a reconnaissance car (capable of everything but weighing nothing, ever since the Great War). Those in charge at the Quartermaster Corps weren’t listening until they witnessed the German blitzkrieg of 1939 and then met a persistent man by the name of Charles “Harry” Payne.

With a new war fast approaching in the late 1930s, the Army knew it had to develop new munitions, but drew a blank when it came to a light scout car. Four car manufacturers were already working on such projects in the hopes to win lucrative government contracts: American Bantam, Willys-Overland, Marmon-Herrington, and Minneapolis Moline.

Harry Payne was a retired Navy pilot hired by American Bantam Motors as a lobbyist to work with the Army Quartermaster Corps (QMC) in the scout car’s development. He presented to the QMC two small Bantam trucks in 1938, and quickly found out what it didn’t want in an army scout car. Payne reported to Senator Harry S. Truman, then chairman of the Committee on Military Affairs (he was investigating abuses while the nation prepared for war). Desperate for ideas and unwilling to be called into Truman’s committee, officers from the QMC visited the Bantam factory in 1940 and learned everything they could about possible light recon vehicles.

The U.S. Army wanted four-wheel drive with a two-speed transfer unit and 85 foot-pounds of torque; it needed to carry 660 pounds, including a machine gun and three passengers. Other requirements were a fold-down windshield, running from 3 to 50 miles per hour, and weighing no more than 1,300 pounds. And their timeline was ludicrous: army quartermasters wanted a working prototype in exactly 49 days.

Much to the surprise of the engineers and administrators at Bantam, who assumed they were being tapped for the job, the QMC invited approximately 135 U.S. manufacturers to submit bids for an ultimate scout car, and they had 11 days to do it. The rush was on to beat the competition, or so Bantam thought on July 11, only three weeks after the QMC visit to the plant.

Scrambling to get something down on paper, Bantam’s president turned to Karl Knight Probst, a West Virginian son of a doctor, who started a life of engineering by building a steam-powered bicycle in 1896 that promptly blew up. He dropped out of Ohio State due to illness, studied engineering in France, designed a small car (called the Dunk Do-Do) in 1911, and went to work for a variety of big-name companies of the times—Chalmers, Lozier, and Peerless. He worked for Milburn Electric and revamped their electric car before moving to REO in Lansing, Michigan, to become the chief engineer.

In 1920, because of his doctor’s advice, Probst quit the auto business and went into real estate—at least until Black Tuesday and the start of the Great Depression. He returned to developing auto engineering projects for a variety of car manufacturers, including Willys, General Motors, American Austin, and American Bantam.

Probst wasn’t tremendously anxious to accept the position since it didn’t promise any money up front—only if the contract was accepted by the QMC. Plus, Bantam was completely broke by June 1940. In a circular manner, Probst got a call from William S. Knudsen, not only the former president of General Motors but also the head of the War Production Office, who said:

“This is important to the country. Forget your office. If you bring this off, and I know you can, we’ll see that you get some money.”

At the first meeting, Bantam president Frank Fenn laid out the parameters of the project, explaining that the QMC wanted plans and bids for a new scout car no later than 9:00 AM on July 22. It was July 17, which meant that Probst had exactly five days to design a whole new vehicle from the ground up (of course, Bantam had already done a number of preliminary designs).

Karl Probst and his team walked into Bantam’s long-deserted drafting rooms, dusted off a couple of drawing tables, rolled up their sleeves, and went to work. Probst worked nonstop through the weekend, taking only a few hours here and there for sleep.

By Friday, July 19, Probst had finished designing what would eventually be America’s greatest recreational vehicle. He knocked off early and went to the movies. On Saturday, he finalized the blueprints, cost calculations, supplier specifications, and bid forms. Probst and Fenn piled into a Buick and headed to Baltimore, where they met up with Harry Payne, who took the wind from beneath their wings when he pointed out that, at 1,850 pounds, it was overweight and unacceptable. Fenn and Probst could do nothing but turn in the designs as they were.

Waiting outside the QMC offices at Camp Holabird at 9:00 AM were representatives from Ford, Crosley, and Willys. Only Bantam had what could be considered a complete bid, as the next best thing was Willys’ crude sketch—and while its bid was lower than Bantam, they bowed out because they had no real plans and probably couldn’t build the 70 prototypes in the required 49 days.

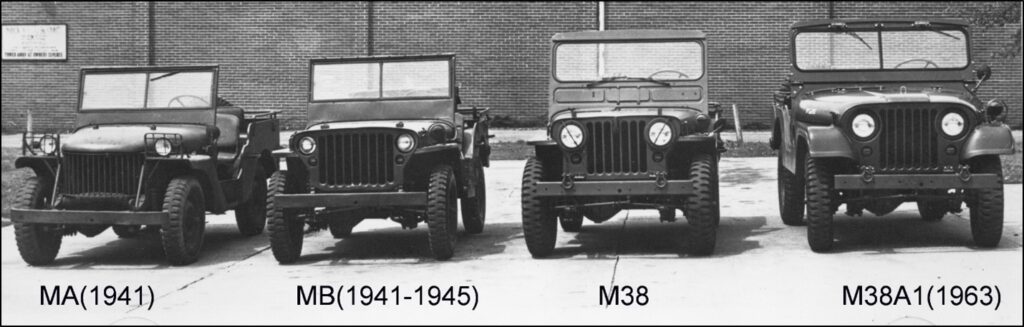

The officers at the QMC took only 30 minutes to reach a conclusion, and the contract with Bantam eventually saved the company . . . so they thought. Ford and Willys ended up outproducing Bantam, who only made 2,643 units during the war—compared to nearly 600,000 from Ford and Willys—and it was Willys’ final design (each company was allowed to make tweaks) that became the official “Jeep.”

In the end, Probst was paid only $200 for his monumental work. But the real work was yet to be done, as the first of 70 working examples—40 to the infantry, 20 to the cavalry, and 10 to the field artillery—was due at the Camp Holabird motor depot no later than 5:00 PM on September 23, 1940.

Mostly unsung, Karl Probst never received official credit for his designs (Willys claimed during the war that it had designed the Jeep). He is often not even mentioned in Jeep history books, and his name isn’t even on the memorial plaque at the Jeep’s birthplace in Butler, Pennsylvania. He went on with his life, working at various auto design firms until his retirement—claiming that his work on the Jeep was a high point of his life.

During a particular torturous battle with cancer in 1963, on August 25, Probst laid out the original drawings of the Jeep on his bed at his Dayton, Ohio, home and took a fatal dose of sleeping pills.

The Father of the Jeep was 79 years old.

ChiltonLibrary recently released factory service manual updates to its Jeep and other Stellantis models. Interested in seeing ChiltonLibrary in action? Tap here to request a free trial or contact your Gale consultant.

About the Author

Ryan Price is the author of The VW Beetle: A Production History of the World’s Most Famous Car, 1936–1967 and other titles. Not only is Ryan Lee Price a freelance writer specializing in automotive journalism, he also was a longtime magazine editor and an essential member of the Chilton editorial team.