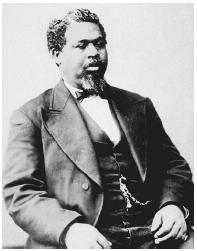

During Black History Month, we honor African Americans who made significant contributions to American society and impacted the course of American history. One such figure is Robert Smalls, who was born a slave in South Carolina, made a dramatic escape from slavery, and was later elected to Congress. With primary sources, Smalls’ remarkable life, achievements, and impact can be considered and understood through contemporary accounts.

Born in 1839 in Beaufort, South Carolina, Robert Smalls was the son of a house slave named Lydia and an unknown father. His mother was one of many slaves owned by the McKee family, and his father may have been one of the McKee men or perhaps their plantation manager, Patrick Smalls. No matter who his father was, Smalls was treated better than other enslaved children, and he was more accepted in the local white community.

Because of this favoritism, Lydia took action to ensure that her son understood the true nature of slavery arranging for him to labor in the fields and watch slaves at “the whipping post.” Working in the fields himself as a young boy, Smalls became insubordinate and was jailed several times. To keep her son safe, Lydia convinced the McKees to let him be hired out for work in Charleston.

There, Smalls held a series of jobs during his teenage years and was allowed to keep one dollar of his weekly wages. He also met a slave named Hannah, who became his wife and the mother of his two children. While living in Charleston, Smalls became employed on the Confederate war ship the Planter, which was anchored in the Charleston harbor.

Daring Escape to Freedom

Because Smalls could not afford the $700 needed to buy his wife and children from their owner, he began formulating a plan to win freedom for all of them. After the start of the Civil War in April 1861, Union ships blocked all harbors in Southern seaports, including Charleston. By September of that year, Union policy for Navy commanders was to accept runaway slaves as contraband. Smalls prepared to take advantage of this practice, and was ready when the opportunity presented itself on the evening of May 12, 1862.

After the white officers left the Planter for the night, most of the slaves aboard joined Smalls and his plan to use the ship to escape to freedom. Donning the distinctive straw hat worn by the ship’s white commander, Captain Rylea, Smalls put the Planter in motion. He made it seem like the ship was sailing on official duty by giving the correct signals at Confederate checkpoints. After picking up Smalls’ wife and children, and family members of other slaves taking part in the plot, the Planter headed to the ships in the Union blockade.

During the voyage, Smalls had the Confederate flags replaced with a white sheet. As Confederate forces realized that the Planter had gone to the Union side, the U.S. Navy also recognized that the Planter was not there to attack them but to surrender to the U.S.S. Onward. In addition to acquiring a well-constructed naval vessel with 200 rounds of ammunition and six guns, the United States gained knowledge about Charleston, the Confederacy, and its ships from Smalls.

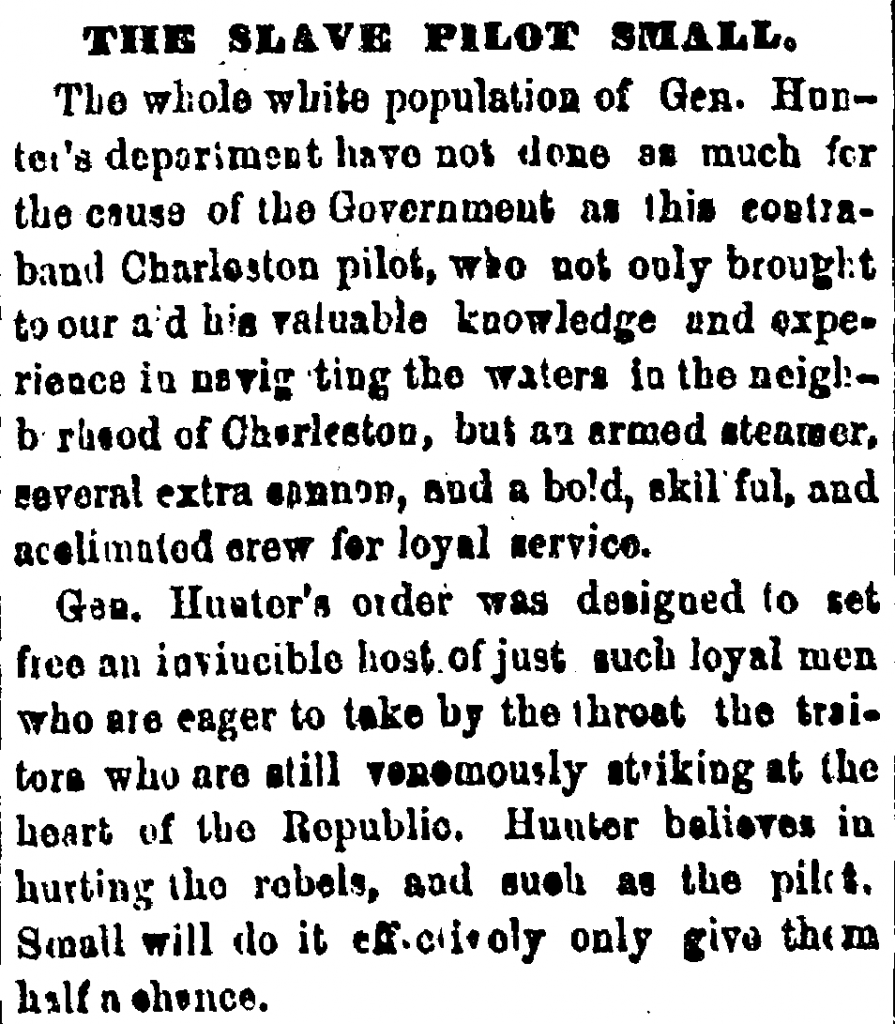

Newspaper accounts from the North lauded Smalls’ actions on the Planter. In a November 1862 account in the Santa Fe Republican, the author praised Smalls in two ways: “first, for his fidelity to his domestic relationships, and secondly, for the foresight, ingenuity, comprehensiveness, and energy which he displayed in making his escape.”

Served in Union Navy

In the Union, Smalls became an instant hero. By the end of May, Congress passed a bill that gave Smalls and his crew half of the proceeds for the ship they brought to the Union. This resulted in $1500 for Smalls alone. Smalls used his newly acquired prestige to ask Edwin Stanton, the Secretary of War, to allow black soldiers to enlist in the Union army. Within a few months, such enlistment became Union policy.

However, there were rumors that Smalls had applied for passage to Central America. In Primary Sources, a letter from Smalls to the editor of the Lowell Daily Citizen dispels this notion. Smalls writes, “I wish it understood that I have made no such application; but, at the same time, I would express my cordial approval of every kind and wise effort for the liberation and elevation of my oppressed race.” his note concludes, “we wish to serve till the rebellion and slavery alike are crushed out forever.”

By October 1862, Smalls had returned to the Planter as a pilot. During the last years of the Civil War, he took part in at least 17 military actions, including an attempt to retake Fort Sumter on April 7, 1863. Because of his valiant leadership, Smalls was promoted to captain. By the end of the war, he was receiving $150 per month in pay, one of the highest salaries among the black soldiers serving in the Union military.

Elected to State and Federal Office

After the war, Smalls bought his former owners’ home in Beaufort and continued to challenge the status quo. A successful businessman who owned a general store and a newspaper, he also began a political career in South Carolina. After stints in the state assembly and senate, Smalls served in the U.S. House of Representatives for five nonconsecutive terms between 1874 and 1886.

Smalls took legal action when he felt black voters were intimidated and subjected to violence, and when their votes were not counted or other fraudulent activities were evident. The legal brief related to a contested election in South Carolina’s Fifth District can be read here. Smalls was the contestee in this case, which was concerned with voting for a member of the Forty-Fifth Congress in 1876. The document includes numerous details about the case and the testimony of affected voters and other related parties.

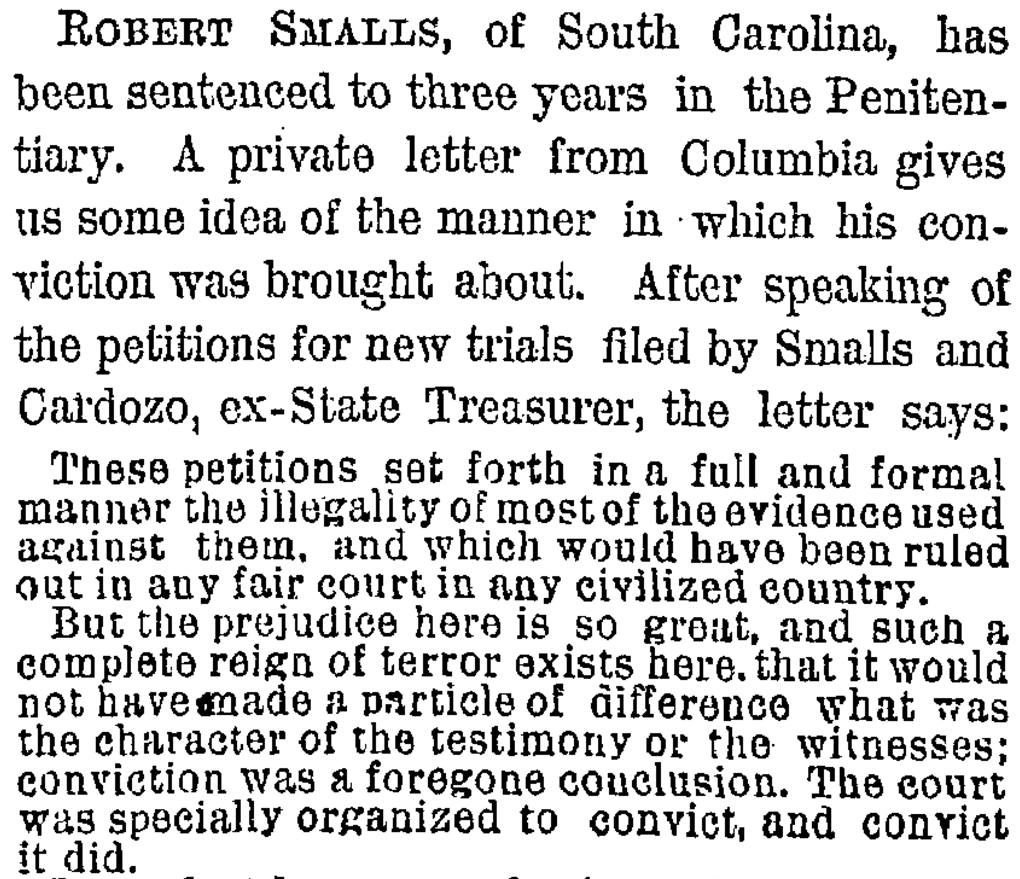

Smalls personally experienced legal action that was intended to terrorize him and bring him harm. In 1877, he was convicted of taking a $5000 bribe while serving in the South Carolina senate despite the accusation having a partisan taint and proof of illegal evidence being used at trial. According to a November 1877 newspaper article in the Chicago-based Daily Inter Ocean, Smalls was sentenced to three years in prison. A jury of black and white men convicted him, but the black jurors reported that the white jurors threatened their lives unless they found Smalls and his co-defendant guilty. During his appeal, Smalls was released and the governor pardoned him in 1879.

Less than a decade after Smalls’ Congressional career came to an end, Reconstruction was rolled back in South Carolina when a new constitution was ratified in 1895. At that time, the voting rights of African Americans were eliminated. By then, Smalls was working as a U.S. Customs collector in Beaufort, a position he held until 1911. He died in February 1915 in the same Beaufort home where he had been born.

Follow our blog all month long as we pay tribute to African American men and women who have overcome adversity and discrimination and affected positive change in the world. Next week we will take a look at the groundbreaking Brown v. Board of Education case.2020 Nike Air Jordan 1 Mid GS “Pink Quartz” 555112-603