In April 2025, a new digital ID program was launched in three communities in New South Wales, Australia. Instead of flashing a driver’s license or pulling up a mobile pass, participants verify their identity using facial recognition technology integrated into the Service NSW app.

Users take a live selfie to match against a government-held reference photo, such as a driver’s license or passport. This allows them to access government services, confirm professional qualifications, or verify age for restricted purchases without having to share unrelated personal information like their full name or address.

For those without licenses—including many elderly or disabled residents—it’s being marketed as a faster, safer way to access services. Critics, however, warn it normalizes constant surveillance.

Facial recognition has already become part of daily life for many students, from unlocking smartphones to tagging photos on social media, but its use stretches beyond convenience. The same systems that make everyday tasks easier can also raise questions about privacy, consent, and how user-generated data perpetuates and amplifies human bias.

The Facial and Biometric Recognition topic page available in Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints offers students a framework for investigating how facial recognition technology is changing how they interact with the world. With up-to-date reporting, viewpoint essays from all sides of the issue, and multimedia content to engage students in learning, the platform gives them space to examine competing claims—from arguments about public safety and efficiency to concerns about civil rights and bias.

How Facial Recognition Technology “Sees” You

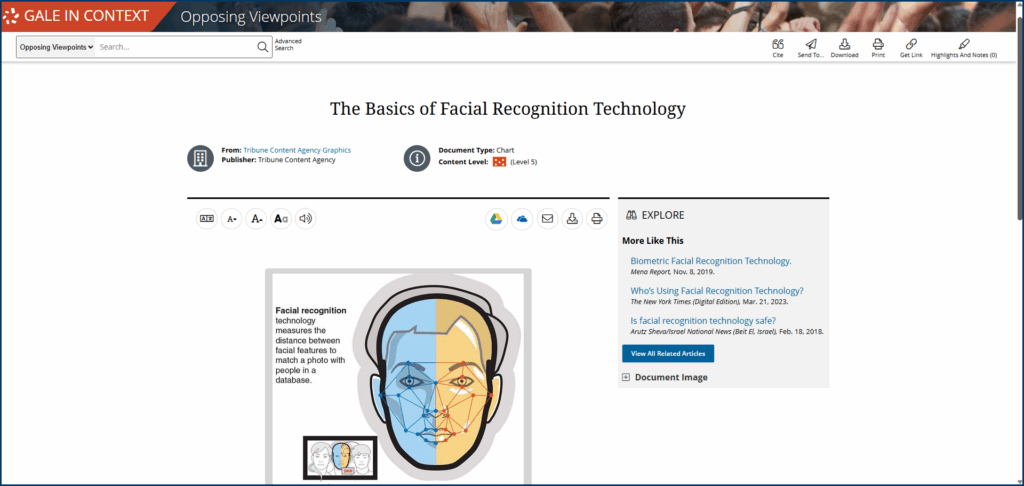

Facial recognition software doesn’t see a person as a human does. Instead, it identifies patterns and uses them to draw conclusions.

Creating those patterns starts with a scan, during which the system maps approximately 80 nodal points of a person’s face: the distance between the eyes, the chin’s shape, the cheekbone contour, etc. These measurements become data points representing a faceprint. When the software compares that faceprint against a database of stored images, it assesses whether the geometry aligns with an image on file and, if successful, returns a match.

How the Technology Learns

Modern facial recognition systems are powered by machine learning, meaning the software doesn’t follow a single hard-coded rule but improves by studying examples.

One of the most widely used training datasets in early commercial systems was called Labeled Faces in the Wild. It included more than 13,000 images collected from the internet. Because the photos were candid, this dataset helped facial recognition technology learn to identify faces in everyday environments, where inconsistent lighting and partial angles are likely.

Some companies now train models on millions of images pulled from everything from mugshot databases to driver’s license registries to scraped social media profiles. More data means better pattern recognition, but it raises questions about the ethics of using people’s faces within a database without their knowledge or consent.

A Question of Consent

Clearview AI built its facial recognition system by scraping billions of images across the internet, many from platforms like Facebook and Instagram. If the image was public, the software treated it as usable. A snapshot from a birthday party or a photo at an amusement park can become part of a system designed for, as the company advertises, “law enforcement to investigate crimes, enhance public safety, and provide justice to victims.”

While users may technically agree to a social media platform’s terms of service when they upload photos, the people captured in the background of those images haven’t given that same consent. And even those who do post their own photos often don’t realize that sharing publicly means it’s available for facial recognition training. But once a photo is scraped, it becomes searchable and nearly impossible to remove.

A March 2022 Clearview press release claims that their 2.0 program “is currently being rolled out to the company’s existing clients, which include more than 3,100 agencies across the U.S. including the FBI, the Dept. of Homeland Security, and hundreds of local agencies.” In some states, including New Jersey and Vermont, police have used it in investigations without notifying public officials, sidestepping any opportunity for civic oversight.

Although there’s no federal framework in place yet, there is growing momentum behind regulating facial recognition. In 2019, Senators Chris Coons and Mike Lee introduced bipartisan legislation that would have required federal agencies to obtain a warrant before they could use facial recognition for surveillance, but the bill never made it out of committee.

As of early 2025, 15 states have policies governing how police can use the technology. Some now require a warrant before searches can be conducted; others focus on procedural transparency, like notifying defendants when facial recognition technology was part of the investigative process. Lawmakers in at least seven additional states have proposed new bills to further define the boundaries of law enforcement use.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How do you feel about facial recognition systems being trained using real people’s photos, often without their knowledge or informed permission? Should companies be required to obtain consent before using someone’s face to train technology?

- Facial recognition can verify identity—like matching a traveler to their passport—or identify unknown individuals by scanning crowds and comparing faces to vast image databases. How is verification ethically distinct from identifying unknown individuals?

- What risks to free expression and political participation could arise if facial recognition is used broadly in public spaces? Should government agencies be allowed to reference mass identification technology from events like protests or political gatherings without specific suspicion of criminal activity? Why or why not?

The Practical Value of Facial Recognition

Facial recognition technology comes up in public debate due to high-stakes controversies, but it wasn’t designed only for policing or surveillance. In many real-world applications, it solves problems that older systems couldn’t address.

Locating Vulnerable Individuals

In 2018, Delhi police launched a pilot project using facial recognition software to help locate missing children by comparing photographs of children living in institutional care against a national database of missing person reports. The initiative, developed in partnership with the child rights NGO Bachpan Bachao Andolan, founded by Nobel Peace Prize laureate Kailash Satyarthi, used software that could analyze thousands of faces in hours.

In the first four days of the trial, nearly 3,000 children were identified as matches, some of whom had been missing for years. This ability to reconnect families demonstrates how facial recognition technology far surpasses the level of mere convenience.

Similar efforts are helping with reunification efforts during the ongoing war in Ukraine. In 2023, The Financial Times conducted a groundbreaking investigation using publicly available photos of missing Ukrainian children and children listed for adoption in Russia. Reporters used facial recognition software to compare thousands of images across two separate databases to identify children taken during the conflict and re-registered under new names and biographical details. The investigation revealed that some children had been given false identities and listed for adoption in Russia without the knowledge of their families or the government.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Under what circumstances should speed and efficiency be prioritized over privacy? How should emergency situations be accounted for?

- Are there dangers in framing certain uses of technology as “exceptions” to ethical concerns? Who decides when an exception is justified? Under what criteria?

When the System Gets it Wrong

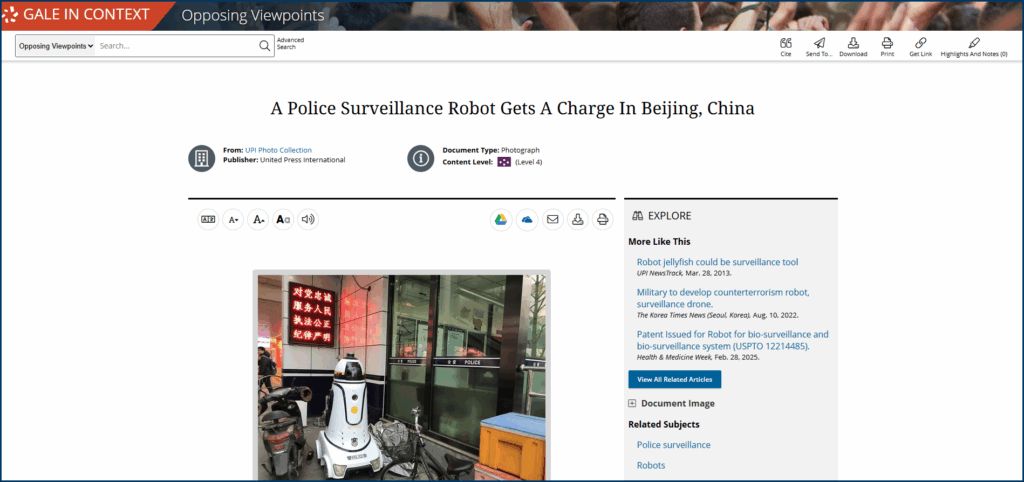

Facial recognition technology can feel harmless when we use it for convenience, like unlocking a phone or speeding up airport check-in. However, when the same systems are used in high-stakes environments like policing or public surveillance, a simple mismatch can lead to life-altering consequences based on faulty data.

Who Pays the Price for a Bad Match?

In 2020, Robert Williams was arrested in front of his family, held overnight in a Detroit jail, and accused of a crime he didn’t commit. The sole evidence in the case was a facial recognition match from a blurry security camera. Williams, a black man, had been flagged by the software, and police never verified the result before making the arrest. It wasn’t until he was in custody that investigators realized the mistake. Williams was the first known case of a wrongful arrest caused by facial recognition in the United States, but not the last.

A 2018 study by the MIT Media Lab found that facial recognition software had significantly higher error rates when identifying women and people with darker skin. The problem is so pervasive that IBM canceled its facial recognition programs the same year as Williams’s arrest. CEO Arvind Krishna released a statement that the company “firmly opposes and will not condone uses of any technology, including facial recognition technology offered by other vendors, for mass surveillance, racial profiling, violations of basic human rights and freedoms.”

For some commercial systems, the misidentification rate for darker-skinned women was over 34%, compared to 0.8% for lighter-skinned men. These differences stem from training data: if a system is trained mainly on one type of face, it becomes more accurate for that group and less accurate for others.

As Lauren Rhue, assistant professor of information systems and analytics at Wake Forest University in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, explains, “There is good reason to believe that the use of facial recognition could formalize preexisting stereotypes into algorithms, automatically embedding them into everyday life.”

Critical Thinking Questions

- If a system is statistically more likely to misidentify certain groups, can its use be justified in criminal investigations?

- What standards should be in place before law enforcement relies on technology that distributes harm unevenly?

Facial recognition technology is no longer a distant or emerging innovation but an increasingly present feature of both our personal devices and public infrastructure. For students growing up alongside these systems, the questions go beyond convenience or safety. They’re about control, transparency, and what it means to participate in digital systems they didn’t choose.

Gale In Context: Opposing Viewpoints helps students examine those questions directly, and our entire database collection further supports those learning opportunities. To learn more about how Gale can encourage deeper thinking and more lively discussions in your classroom, please contact your local sales representative to learn more or request a free trial.