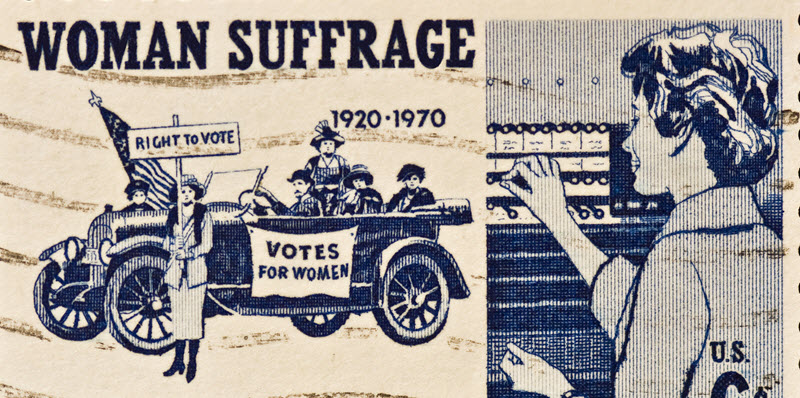

Women’s suffrage is a relatively recent accomplishment in U.S. history. On August 26, U.S. Secretary of State Bainbridge Colby officially certified the 19th Amendment, which legally protected a woman’s right to vote. The original U.S. Constitution did not guarantee women that right, and the ultimate success of the women’s suffrage movement demanded years of turmoil and occasional violence.

Momentum for the women’s suffrage movement began to build in the mid-19th century. Led by key figures such as Susan B. Anthony and Elizabeth Cady Stanton, women’s suffrage supporters spent decades organizing, marching, and lobbying for a constitutional amendment that would guarantee women the right to vote. Anthony died in 1906 before the amendment was passed, but her legacy encouraged campaigners to continue the fight. Despite later legal challenges, the Supreme Court upheld the 19th Amendment’s historical passage.

Academic librarians can raise appreciation for these important historical moments—and broaden campus awareness about the power of Gale OneFile: Contemporary Women’s Issues to better understand them. Researchers can leverage popular press and academic articles to understand the trajectory of the movement as it evolved over the better part of a century.

As the spring semester gets underway, share this invaluable tool with faculty and staff in your history, literature, and women’s and gender studies classes. And with Women’s History Month approaching in March, Contemporary Women’s Issues can help uncover fascinating moments from the movement that you can share on social media or curate in library displays. The story leading up to the 19th Amendment’s ratification is a compelling journey that’s worth remembering. In honor of the courage and activism that helped codify women’s right to vote, you can create a timeline that illustrates the scope of the 19th Amendment, the delicate partnership alongside the abolitionist movement, and the powerful characters involved. This timeline of women’s rights in the United States provides an essential foundation for understanding the evolution of women’s rights over the past century, demonstrating how small, meaningful acts can spark momentous change. This resource may inspire your students to recognize the ongoing importance of advocacy for equal rights.

The Journey to Women’s Suffrage

1848: Activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, and Jane Hunt meet for tea. The women decide to organize a group to further the “social, civil, and religious condition of women.” In response, hundreds of people gather in Seneca Falls, New York, to attend the Women’s Rights Convention. Attendees discuss topics to include in a formal Declaration of Sentiments; after two days, they decide on a formal list and ultimately outline an agenda for the official women’s suffrage movement. Find supplemental biographical information and editorial pieces through Gale OneFile: Contemporary Women’s Issues to learn more about this momentous gathering.

1851: Formerly enslaved person Sojourner Truth delivers her “Ain’t I A Woman?” speech to a predominantly white audience at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. The oration is considered one of U.S. history’s most influential women’s rights speeches.

1866: Following the end of the Civil War, Stanton and Anthony launch the American Equal Rights Association. The organization aims to secure universal suffrage regardless of race or sex.

1868: The country ratifies the 14th Amendment granting citizenship and its associated liberties to all people born or naturalized in the United States. That same year, Kansas Senator Samuel Pomeroy campaigns for a women’s suffrage amendment. Congress rejects his proposal.

1869: Disagreement over the impact of the 14th and proposed 15th Amendments leads to division among women’s suffrage leaders. Stanton and Susan B. Anthony create the radical National Woman Suffrage Association (NWSA) to secure women’s Constitutional right to vote. Other leaders form the American Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA), a more conservative group.

1870: The country ratifies the 15th Amendment, giving all men, including formerly enslaved people, the right to vote. Controversially, Anthony and Stanton denounce the amendment, pursuing universal suffrage as their primary goal. Their decision to not support the 15th Amendment causes a rift within the suffragist movement. With Gale OneFile: Contemporary Women’s Issues, you can dig further into the contentious separation of the two groups.

1872: In an act of civil disobedience, 15 women—Anthony among them—cast ballots in the presidential election. Two weeks later, Anthony is arrested for illegally voting. At her trial, she argues that U.S. women are taxed without representation, undermining the country’s basic philosophical foundations. Despite her argument, the jury finds her guilty and fines her $100, which she refuses to pay.

1878: Through an organized petition, Anthony and Stanton gathered enough support to introduce the Women’s Suffrage Amendment to Congress. While the law doesn’t pass for another 40+ years, their initial language remains unchanged.

1890: Led by Stanton, the two predominant suffragist organizations—NWSA and AWSA—combine efforts and become the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). Meanwhile, Wyoming officially becomes a U.S. state; as a territory, it already allowed women the right to vote, making it the first state in the nation to formally grant women’s suffrage. Colorado (1893) and Idaho (1896) soon follow.

1906: Susan B. Anthony dies. She does not live to see the 19th Amendment pass. However, to this day, admirers leave their “I Voted” stickers at her grave in Rochester, New York.

1911: The National Association Opposed to Women’s Suffrage forms. Many of its members are wealthy women who claim that the right to vote would destroy family values.

1912: Individually, Oregon, Arizona, and Kansas grant women the right to vote at the state level. Meanwhile, Theodore Roosevelt supports women’s suffrage while running for president, placing the topic firmly within the national conversation.

1913: Thousands participate in a NAWSA-organized march down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington, DC, the day before Woodrow Wilson’s inauguration. Some onlookers turn violent, tripping and even attacking some of the marchers; more than 100 women are hospitalized. The spectacle garners media attention and sympathy for the cause.

1916: Montana elects social worker Jeanette Rankin, the first woman in the House of Representatives.

1918: Representative Rankin pushes for women’s suffrage at the federal level, and the House successfully passes the amendment; however, it fails in the Senate. President Wilson directly addresses Senate members and implores them to support women’s right to vote.

1919: The Senate passes the 19th Amendment.

1920: Tennessee becomes the 36th state to ratify the 19th Amendment, tipping the scales and achieving the two-thirds majority needed.

As mentioned, the 19th Amendment may have passed into law, but it still faced legal challenges after the fact, notably from the state of Maryland. Noteworthy Baltimore attorney Oscar Leser argued that despite the 19th Amendment earning the two-thirds majority needed to become law, Maryland had no obligation to honor those changes. The controversial case went to the Supreme Court, and on February 27th, 1922, the Court rejected Leser’s challenge.

No matter what century we live in, fundamental human rights require constant protection. By sharing the story of women’s suffrage through Gale OneFile: Contemporary Women’s Issues, college librarians can integrate vetted, reliable information and create a space for ongoing positive change.

Ready to explore but not an active subscriber? Contact your local sales representative to learn more and access a trial.