| By Gale Staff |

The 2025 film adaptation of Animal Farm promises to breathe new life into George Orwell’s satire of the Soviet Union for a modern audience. However, the story’s symbolism contains a complex and profoundly important message that risks misinterpretation without the necessary context.

What better place to help your students appreciate this classic satire on communism than in your English classroom?

Gale In Context: Literature boasts more than 300 topic pages, giving students an easy entry point for age-appropriate work overviews. This in-depth research database also provides contextual information, including primary sources from the authors’ time period, present-day tie-ins, and multimedia content.

To help bridge the gap between history and Orwell’s allegory, let’s dig into the Animal Farm and George Orwell topic pages for tools to help educators scaffold the chronology, characters, and basic metaphors of the novella.

Getting Started: Meet the Author and the Animals

Earlier in life, George Orwell had aligned himself with Marxists—even fighting alongside the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification during the Spanish Civil War in 1936. However, this experience gave him a first-hand perspective on the Soviet-backed faction’s power-hungry tactics.

The author became disillusioned as he watched the betrayal of Marxist principles by self-serving leaders who replicated the systems of oppression they sought to overthrow. And so, in 1945, Orwell published Animal Farm, a satire of the Soviet Union and its descent into dystopic authoritarianism under Stalin.

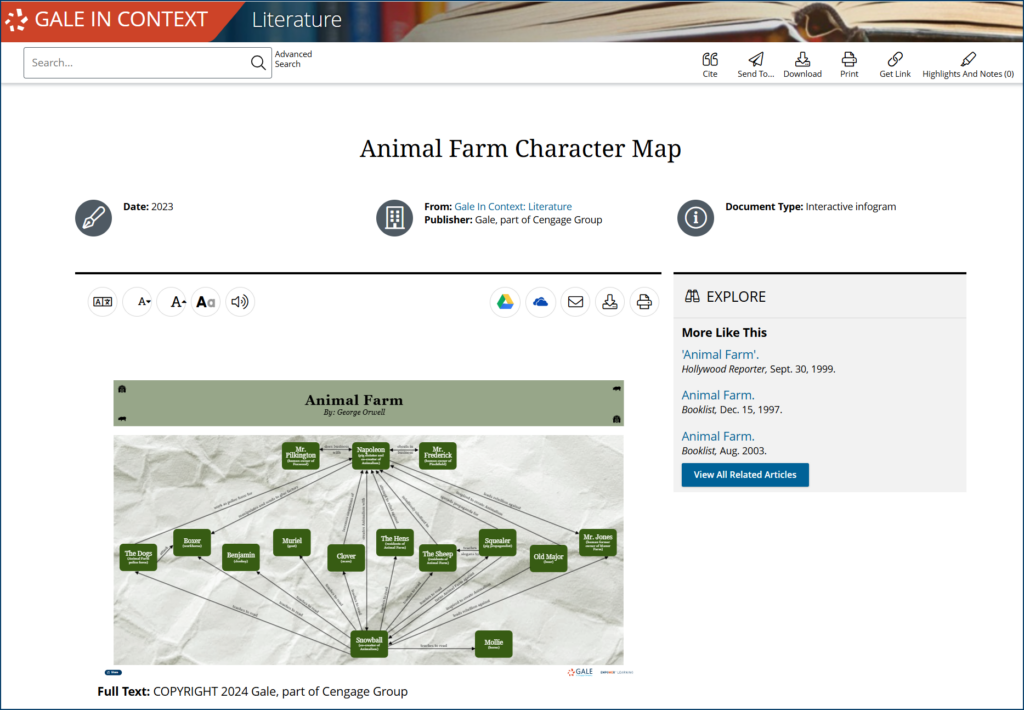

The fable is populated by anthropomorphized animals, starting with Old Major. This wise and visionary boar inspires the animals to rebel with his dream of a society built on equality, echoing the philosophies of Karl Marx and Vladimir Lenin that sparked the Russian Revolution.

The animals’ rebellion leads to a power struggle between two pigs: Napoleon, the manipulative and authoritarian leader who mirrors Joseph Stalin, and Snowball, the idealistic but ultimately ousted rival representing Leon Trotsky.

Other characters, such as Boxer, the hardworking horse, and Squealer, the persuasive propagandist pig, embody the exploited working class and the authoritarian regime’s manipulation of language and media.

To help students make these connections, we recommend using our Animal Farm Character Map, an interactive infographic that illustrates the roles and relationships within the text.

The Revolution

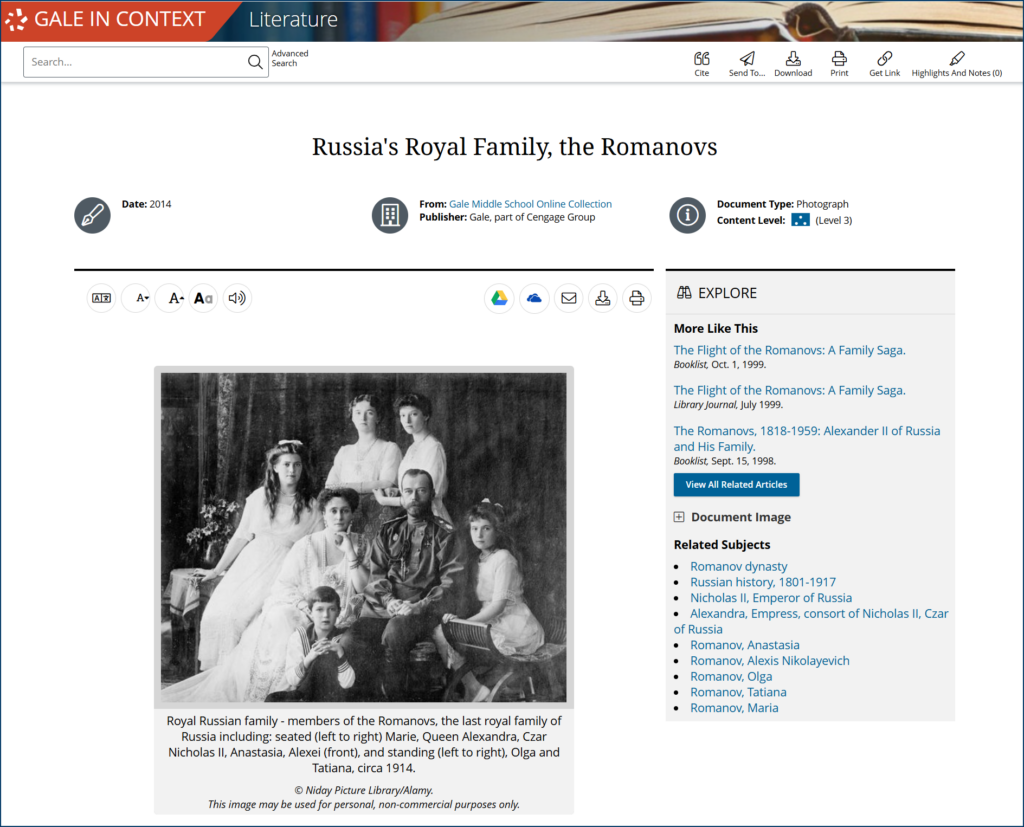

By the early 20th century, the Romanov dynasty, which had ruled Russia since 1613, faced collapse under the leadership of Tsar Nicholas II. His poor governance and failure to address worker unrest, widespread poverty, and food shortages, combined with disastrous military losses in World War I, created a volatile environment ripe for revolution.

During the February Revolution of 1917, Tsar Nicholas II abdicated, creating a power vacuum that allowed Vladimir Lenin of the Communist Party to take control.

Relating the Events to Animal Farm

At the book’s opening, Mr. Jones—the farm owner—neglects his animals to the point that he forgets to feed them. His ineptitude mirrors the failures of Tsar Nicholas II and creates the conditions for their revolt. Old Major encapsulates this injustice in his rallying speech, declaring: “Man is the only creature that consumes without producing . . . He sets [animals] to work, he gives back to them the bare minimum that will prevent them from starving, and the rest he keeps for himself.”

The animals’ victory over Mr. Jones paralleled the revolutionaries’ expulsion of the Tsar, and their hope for a better future—just as the Russian people initially celebrated the end of autocratic rule and, they hoped, their suffering.

Early Promises

In the wake of the February Revolution, the Bolsheviks—led by Lenin—acted quickly to fulfill their promises of “Peace, Land, and Bread.”

First, they brought peace by withdrawing from World War I through the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk. Land redistribution gave property to peasants, while the New Economic Policy (NEP), launched in 1921, revitalized agriculture by replacing harsh wartime rationing with a tax-in-kind system that incentivized farmers to produce more.

Relating the Events to Animal Farm

Like the Bolsheviks, the animals’ early attempts to organize their new society included adopting policies (“the Seven Commandments”) to serve as the foundation of the utopian egalitarianism they call Animalism.

To distinguish their new system, the Seven Commandments included tenets rejecting human behavior, such as “Whatever goes up on two legs is an enemy,” “No animal shall wear clothes,” and “All animals are equal.”

The Power Struggle

After Lenin died in 1924, the unity of the Bolshevik leadership unraveled, and a power struggle emerged between Trotsky and Stalin. Stalin expelled his rival from the Communist Party in 1927, exiled him from the Soviet Union in 1929, and eventually ordered his assassination in 1940. After Trotsky’s expulsion, Stalin’s control became absolute, and the revolution’s ideals gave way to a totalitarian state.

Relating the Events to Animal Farm

Old Major’s death before the rebellion parallels Lenin’s passing—as does the fact that his skull is displayed as a symbol of the revolution, much like Lenin’s embalmed body displayed in Red Square.

The patriarch’s death leads to conflict. Snowball, like Trotsky, is an idealist leader with grand plans for progress, such as a windmill. However, Napoleon undermines Snowball’s efforts, ultimately using brute force to seize control when he expels Snowball from the farm with the help of his trained dogs: “They dashed straight for Snowball, who only sprang from his place just in time to escape their snapping jaws. In a moment he was out of the door and they were after him . . . By the time he had halted, the other animals were coming up, and Napoleon, with the dogs following him, now mounted onto the raised platform.”

Consolidation of Power

One of Stalin’s first moves after Trotsky’s exile was reversing the NEP, consolidating farms into state-run collectives under the guise of industrialization. This policy displaced millions of families and caused catastrophic famine, including the Holodomor—a word implying starvation-induced extinction—in Ukraine.

Stalin also launched an aggressive propaganda campaign to rewrite history, erasing or vilifying political rivals. Trotsky, for example, was removed from photographs and labeled a traitor—a revisionist tactic that legitimized Stalin’s leadership.

Relating the Events to Animal Farm

With Snowball gone, Napoleon consolidates power and begins manipulating the commandments to justify the pigs’ increasing privileges.

For example, when the pigs start drinking alcohol, they amend the rule “No animal shall drink alcohol” to “No animal shall drink alcohol to excess.” Similarly, when they begin sleeping in beds—a practice associated with the humans they once despised—the commandment “No animal shall sleep in a bed” is revised to read “No animal shall sleep in a bed with sheets.”

Silencing Dissenters

Stalin’s consolidation of power culminated in the Great Purge (1936–38), an operation during which the secret police, directed by Genrikh Grigoryevich Yagoda, targeted perceived enemies amongst the Bolsheviks, Communist Party, and society at large.

In just two years, millions of supposed dissenters were put into the Gulag labor camps. Additionally, the vast majority of “old” Bolsheviks were sentenced during the Moscow Show Trials and an estimated 750,000 people were executed.

Meanwhile, the public was bombarded with images and stories reinforcing the narrative that he was rooting out treachery to protect the revolution, manipulating the people to accept suffering and inequality that had replaced the initial promises of “Peace, Land, and Bread.”

Relating the Events to Animal Farm

In Animal Farm, Napoleon employs similar tactics to silence dissent. His trained dogs function as a private militia, instilling terror among the animals and killing indiscriminately. Napoleon’s rhetoric also parallels Stalin’s propaganda, framing repression as a benevolent act, suggesting that Napoleon’s actions are solely to protect the animals from harm.

The animals’ fear of retribution culminates in a chilling display of loyalty tests and purges. Napoleon accuses the animals of conspiring with Snowball, coercing them into confessing to false crimes, and then calling for their immediate execution: “They were all slain on the spot. And so the tale of confessions and executions went on, until there was a pile of corpses lying before Napoleon’s feet and the air was heavy with the smell of blood.”

Alliances and Betrayal

While Stalin continued his reign of terror in the Soviet Union, international tensions escalated, culminating in World War II.

In 1939, Stalin shocked the world by signing the Nazi-Soviet Non-Aggression Pact with Adolf Hitler. However, in 1941, Hitler betrayed Stalin by launching Operation Barbarossa, a massive invasion of the Soviet Union, resulting in devastating losses for the Soviets.

Relating the Events to Animal Farm

In Animal Farm, Orwell parallels these historical events with Napoleon’s dealings with neighboring farmers—particularly Mr. Frederick, who represents Nazi Germany. Napoleon sells timber to Frederick, only to be betrayed when he pays with counterfeit money, sparking the Battle of the Windmill.

After the animals have pushed back Frederick’s forces, the windmill lies in ruin, and Napoleon reframes the narrative to maintain his authority, declaring: “But if we have our lower animals to contend with, we have our lower classes! Comrades, do you know who is responsible for this? Frederick and his men. We will rebuild the windmill again!”

Napoleon’s reference to “lower animals” is a common rhetorical device in totalitarian regimes. In these regimes, leaders position themselves as superior stewards of progress while portraying the working class as simultaneously heroic and flawed. Their labor is the backbone of society, yet they are the most susceptible to errors and thus require firm leadership.

Napoleon’s rhetoric also echoes nationalist propaganda, casting external enemies like Frederick as existential threats while rallying the animals around the shared effort to rebuild.

Revolution’s End

The novel concludes with a chilling scene that solidifies Orwell’s critique of power. Napoleon and the pigs host a banquet with the neighboring farmers, playing cards jovially while the animals watch, horrified, from outside the window: “The creatures outside looked from pig to man, and from man to pig, and from pig to man again; but already it was impossible to say which was which.”

This final betrayal encapsulates Orwell’s warning: revolutions without accountability often replace one oppressive regime with another. The pigs’ complete transformation into the oppressors they rebelled against is the result of power becoming concentrated in the hands (or hooves) of the few.

With the help of Gale In Context: Literature, you can spark conversations about the upcoming adaptation of Animal Farm and invite students to examine Orwell’s cautionary tale—not as a grim inevitability, but as a call to question authority and resist manipulation.

You can learn more about Gale In Context: Literature by contacting your local sales representative!