| By Carol Brennan |

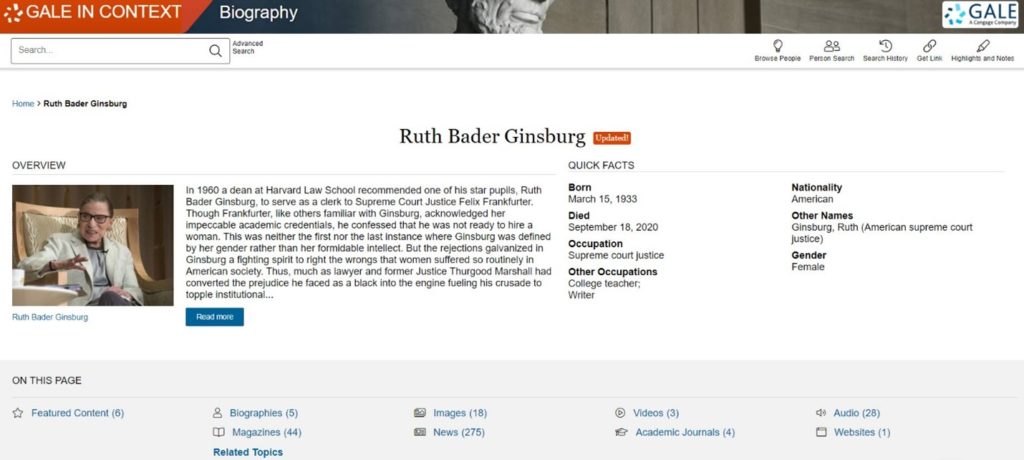

Few American women have attained in their lifetime the revered and folkloric status of Ruth Bader Ginsburg (1933-2020), only the second woman to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court. Appointed to the bench in 1993, Ginsburg spent the next 27 years as one of the last remaining liberal-leaning associate justices on the nation’s high court. She was the 107th American jurist to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court but the first Jewish woman to be confirmed by Senate vote for the lifetime judgeship.

Joan Ruth Bader was a native New Yorker, born at a Brooklyn hospital in 1933. Her mother, Celia (Amster) Bader was the daughter of Polish Jewish immigrants. Nathan Bader, her father, was from a nearby region of Europe that experienced anti-Semitic violence in the late 19th and early 20th centuries and worked as a furrier. The Odessa-born Nathan and his wife grieved the loss of their older daughter, Marylin, when Ginsburg was still in infancy.

A prodigiously gifted student, Ginsburg missed her graduation ceremony at James Madison High School in 1950 due to Celia’s death from cancer on the preceding day. Ginsburg was 17 years old later that year when she met her future husband, Martin Ginsburg, at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. The couple married in 1954, just weeks after Bader graduated Phi Beta Kappa with a degree in government. The couple lived in Oklahoma for a short time while Marty—who went on to become one of the leading tax attorneys in Manhattan—fulfilled his military-service obligation. Their first child, a daughter, was born exactly a year after their marriage.

In the fall of 1956, Ginsburg followed her husband into Harvard Law School, where he had already completed his first year. More than 500 students were in her first-year law class but she was one of just nine women. Marty graduated in 1958 and accepted a lucrative job offer from a New York City law firm; as a result, Ginsburg transferred to the law school at Columbia University, where she graduated first in her class in 1959, an honor she shared with another student.

Despite the numerous distinctions Ginsburg had earned at two Ivy League law schools, she was rejected for a U.S. Supreme Court clerkship and was unable to find a job. She spent two years as a clerk for a federal judge on the bench of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, and another two working on the Columbia Law School Project on International Procedure, for which she learned Swedish. In 1963 she began teaching at Rutgers Law School in Newark, New Jersey, and became a tenured professor six years later. During this decade she emerged as one of the new generation of female legal scholars and activist-lawyers who were seeking to redress gender bias through the judicial system, modeling their strategy after the success of their African American peers who had used legal challenges to force the federal courts to overturn statutes or practices that permitted discrimination on the basis of race.

In 1972 Ginsburg went to work for the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) as co-founder of its Women’s Rights Project. As general counsel, she sought out pending legal cases she thought would benefit from the ACLU’s involvement. A year later, as plaintiff’s counsel for U.S. Air Force officer Sharron Frontiero, Ginsburg argued her first case before the U.S. Supreme Court and won it. This was the 1973 decision Frontiero v. Richardson which restored a lower court’s judgment that Frontiero and her husband were entitled to the same U.S. Department of Defense housing allowance granted to married couples in which the husband was the member of the U.S. armed forces.

Ginsburg argued another five cases before the U.S. Supreme Court and won four of those. All involved gender discrimination, from jury-duty service to Social Security Administration benefits, and, nearly two decades after she graduated from law school, finally elicited the type of job offer for which a law professor and civil-rights advocate was eminently qualified: a seat on the federal bench. President Jimmy Carter nominated her for a vacancy on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit and Ginsburg’s name was affirmed by a Senate vote in June of 1980. Fourteen months later, Carter’s successor, President Ronald Reagan, nominated Arizona judge Sandra Day O’Connor to become the first female associate justice on the U.S. Supreme Court.

In 1993 Ginsburg became the second woman to sit among the nine judges of the U.S. Supreme Court when President Bill Clinton nominated her to replace Associate Justice Byron White, who was 76 years old when he retired. She was also just the fifth justice from a Jewish background and the first of her religion to sit on the high court since the resignation of Abe Fortas in 1969. The first significant victory during Ginsburg’s 27-year tenure came in 1996 with United States v. Virginia, which ordered the all-male Virginia Military Institute to admit qualified female applicants. When Associate Justice O’Connor retired in 2006, Ginsburg remained the only woman on the U.S. Supreme Court until Sonia Sotomayor was confirmed by Senate vote in 2009.

Admirers of Ginsburg included President Barack Obama, who pointedly chose a piece of legislation that was directly attributable to one of Ginsburg’s concisely worded dissents. In 2007, she had objected to her colleagues’ application of the statute of limitations rule regarding plaintiff Lilly Ledbetter, an Alabama woman who had spent nearly two decades with the Goodyear Tire & Rubber Company. Shortly before Ledbetter retired, she learned that three male colleagues had earned a significantly higher salary than her and she sued Goodyear for wage discrimination on the basis of her gender. Before President Obama signed the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, a plaintiff had just 180 days after the date of her last paycheck to petition for redress. Ginsburg’s dissent urged federal lawmakers to repeal that six-month statute of limitations, and they did.

No other Supreme Court justice in U.S. history has been the focus of such fervent popular-culture fandom. Justice Ginsburg was dubbed the “Notorious RBG” for her moral leadership and advocacy of the pillars of American democracy—from supporting the continued protection for the rights of voters as guaranteed in the Bill of Rights to upholding the human-rights tenet that the state shall not interfere with the dominion a woman has over her body.

Ginsburg was touched by the outpouring of support that came as she battled recurring bouts of pancreatic cancer. She was 87 years old when she died of complications from that disease on September 18, 2020, at her home in Washington, DC.

Candlelight vigils and public-mourning events were held in more than 50 U.S. cities. Revered as a standard-bearer for feminists around the world, Ginsburg once told the New Yorker’s Jeffrey Toobin that the legal strategies she deployed as a lawyer arguing cases before the bench of the Supreme Court in the 1970s relied on a quietly rational appeal to reason. “I don’t think they regarded discrimination against women as discrimination at all,” she said of the all-male justices. “These were people who thought they were good fathers, they were good husbands, and they didn’t understand barriers that women faced as discriminatory.”

In the same interview, Ginsburg also credited her long-ago female assistant for suggesting that the term “discrimination on the basis of sex” might be better revised to “discrimination on the basis of gender,” which became the prevailing norm. My secretary said, “I look at these pages and all I see is sex, sex, sex. The judges are men, and when they read that they’re not going to be thinking about what you want them to think about.’”

You can read more about Ruth Bader Ginsburg and other notable women in Gale In Context: Biography.

Not a Biography subscriber? Learn more about this authoritative database >>

Banner image from https://law.uoregon.edu/memoriam-justice-ruth-bader-ginsburg

Meet the Author

Carol Brennan has been writing biographical entries for Cengage/Gale since 1993. If she’s not writing she’s either at yoga or walking her corgi and she consumes an alarming volume of podcasts and audiobooks weekly.

秋コーデ メンズ【2020/2021年最新】 , メンズファッションメディア