Posted on May 4, 2016

By: Daniel Pullian

‘The compartment was much bespattered with blood’: the Brighton Railway Murder

Barely a week went by in the nineteenth-century press without a sensational crime story appearing. Whether it was the gory prospect of blood and dismembered bodies, or simply the thrill of a classic ‘whodunit’, there can be little doubt that crime reporting made compelling copy. This was certainly the case with the ‘Brighton Railway Murder’ which took place in the summer of 1881. From beginning to end, the case captivated the imagination of the British people, eager to discover who had murdered wealthy tradesman Frederick Gold, and what would become of the culprit. A search of Gale Artemis: Primary Sources highlights the case’s notoriety, giving me the perfect opportunity to trace its development.

The context

Mr Frederick Isaac Gold was a retired tradesman who retained an interest in a London business. As The Police Encyclopedia, from The Making of Modern Law, tells us, it was his custom to travel from his home in Brighton to London each Monday morning. Here he would receive the takings from said business, which were often in the region of £40-50 (the equivalent to around £3,000 today). Mr Gold would then deposit this sum in a bank, before returning to Brighton on the express train, in the comfort of a first-class carriage.

It was while he was innocently going about his weekly business one summer afternoon in 1881 that disaster struck…

Adam, Hargrave Lee, The Police Encyclopedia, Vol. 5. London: Waverly, [191??].

The Making of Modern Law: Legal Treatises, 1800-1926

The murder

On 27th June 1881, Frederick Gold was joined on the London to Brighton express train by Percy Mapleton Lefroy. Although both men boarded the train, only one of them was to leave it – at least of their own accord. It was clear from the beginning that something strange was going on. The Daily Telegraph followed the case throughout, reporting on 28th June the discovery of a body in a tunnel along the railway line, with multiple stab wounds. That same day, a man by the name of Lefroy had been found alone in a carriage of the train which had passed through the tunnel, covered in blood. Already, it seemed that the writing was on the wall; the next day, the ‘mystery’ had become a ‘foul act of murder’ (29th June).

An extract from one of the many large articles published on the murder: ‘The Railway Tragedy’, The Daily Telegraph, 29 June 1881.

It appeared that Lefroy had approached Mr Gold in the carriage, perhaps noting his wealth from the open-faced gold Griffiths watch which the latter wore. A struggle ensued, in which gunshots were fired, and blows struck with a knife. Lefroy’s collar was torn off during the combat, although, wielding the knife, he prevailed. It was presumed that he then rolled Mr Gold’s body out of the moving train.

Adam, Hargrave Lee, The Police Encyclopaedia, Vol. 5. London: Waverly, [191??].

The Making of Modern Law: Legal Treatises, 1800-1926

The aftermath

Yet it was an extremely disheveled Lefroy who was first discovered, alone in the first-class carriage. According to the aforementioned Police Encyclopedia, he presented a ‘most alarming aspect’; having taken a wound to the head, there was a significant amount of blood in the compartment. How had this come about? According to Lefroy, he had been approached by an elderly man and attacked without warning while the train passed through the tunnel. He claimed to remember nothing else.

Despite leaving the train with a watch dangling from his shoe, the local police let Lefroy leave after questioning. It was suggested in the above source that Lefroy was still with the police when news of Mr Gold’s discovery filtered through – whatever the case, they evidently saw insufficient reasoning to support Lefroy’s further detention. He thus escaped their clutches, making his way to a relative’s house.

Meanwhile, a man named Thomas Picknell came across a bloodied collar along the railway line. As his witness account outlined, as a ‘ganger’, he was responsible for clearing the tracks of debris. He therefore formed part of the group required to retrieve Mr Gold’s body, which had been found by a colleague further down the line. Even in the dully lit tunnel, Picknell could see enough of the corpse to note signs of a ‘long and fierce struggle’; ‘the face was covered with blood’.

Wood, Walter. Survivors’ tales of famous crimes. London; New York: Cassell, 1916.

The Making of Modern Law: Legal Treatises, 1800-1926

With Lefroy having been found without a collar upon discovery, it did not take long to piece the events together. Yet the suspect was long gone, having fled his cousin’s house. The police promptly offered a reward for Lefroy’s capture.

The significance of the story is clear from the pages of The Daily Telegraph around this time. On 1st July, they pioneered the use of an artist’s impression to print an illustration of Lefroy. This was accompanied by the police description of the suspect: he was ‘very thin’, with a ‘sickly appearance’ and ‘teeth much discolored’. With the drawing accompanied by the prospect of a reward, floods of supposed sightings of Lefroy were reported – leading to the detention of over 20 suspects before the man himself was captured.

The first ever line drawing to appear in a British newspaper: ‘The Railway Tragedy’, The Daily Telegraph, 1 July 1881

The first ever line drawing to appear in a British newspaper: ‘The Railway Tragedy’, The Daily Telegraph, 1 July 1881

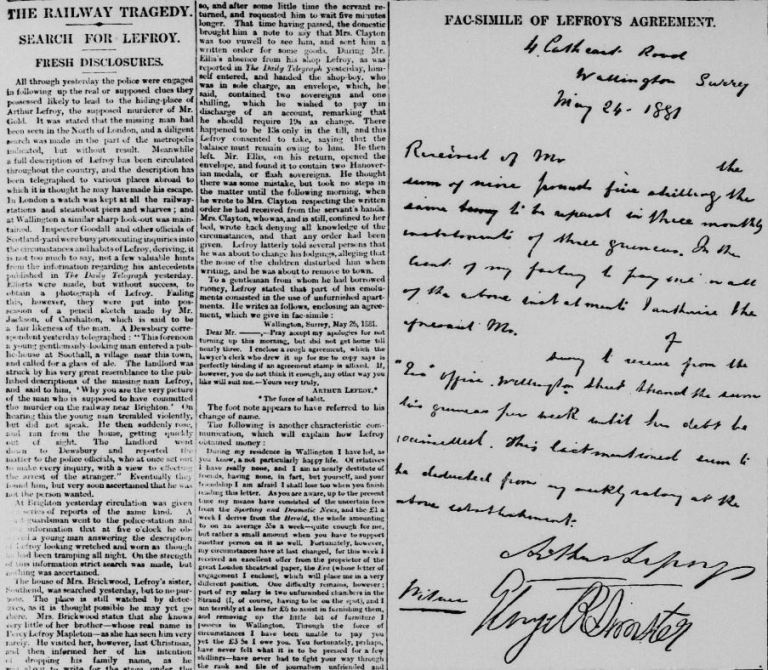

One of the large articles produced by The Daily Telegraph throughout the case – pictured to the right is a facsimile image of an agreement between Lefroy and a gentleman to whom he owed money, ‘Fac-simile of Lefroy’s agreement’, The Daily Telegraph, 30 June 1881.

One of the large articles produced by The Daily Telegraph throughout the case – pictured to the right is a facsimile image of an agreement between Lefroy and a gentleman to whom he owed money, ‘Fac-simile of Lefroy’s agreement’, The Daily Telegraph, 30 June 1881.

Capture and Trial

In fact, it was his own naivety that got him caught. Without a residence, Lefroy decided to rent a room with a Mrs Bickers in Stepney, on 30th June. Impatient to receive his wages, he sent a coded telegram from there, which read as follows:

‘Please send my wages to-night without fail about eight o’clock, Flour to-morrow. No. 33’.

Adam, Hargrave Lee, The Police Encyclopedia, Vol. 5. London: Waverly, [191??].

Adam, Hargrave Lee, The Police Encyclopedia, Vol. 5. London: Waverly, [191??].

The Making of Modern Law: Legal Treatises, 1800-1926

It was its mystery which was perhaps to prove its downfall though; added to the fact that it was addressed to a non-existent ‘Mr Seal’, the message only attracted the attention of two detectives. They promptly visited the property and arrested the unsuspecting Lefroy.

The evidence against Lefroy was overwhelming. The watch he carried was unquestionably that of Mr Gold, while two hats which had been found on the line were proved to be those of the murderer and victim.

‘The Brighton Railway Tragedy – Percy Lefroy Mapleton before the Magistrates at Cuckfield’,

‘The Brighton Railway Tragedy – Percy Lefroy Mapleton before the Magistrates at Cuckfield’,

Graphic, 23 July 1881. British Library Newspapers

The ensuing sentencing, pictured in the pages of The Graphic, was a somewhat foregone conclusion, as was the November trial. Despite Lefroy’s claims that it was merely his intention to frighten a passenger of the train into giving him much-needed money, the jury took a dim view. Percy Mapleton Lefroy was convicted, condemned to death – as the below extract from the Home Office’s Calendar of Prisoners shows – and eventually executed. One of the most notorious criminal cases of the nineteenth century had reached its end.

![]() HO 140/54: After-Trial Calendars of Prisoners Tried at Assizes and Quarter Sessions in the Following Counties:

HO 140/54: After-Trial Calendars of Prisoners Tried at Assizes and Quarter Sessions in the Following Counties:

Hampshire; Herefordshire; Hertfordshire; Huntingdonshire; Kent; Lancashire; Leicestershire; Lincolnshire, 1881. 1881. MS Crime and the Criminal Justice System: Records from The U.K. National Archives: HO 140 Records created or inherited by the Home Office, Ministry of Home Security, and related bodies, Home Office: Calendar of Prisoners HO 140/54. The National Archives (Kew, United Kingdom). Crime, Punishment, and Popular Culture,1790-1920

For more information or to request a trial, please get in touch with us today.Nike Air Max 270