| By K. Lee Lerner |

Man’s footprint remains No wind or rain to erode Mankind’s achievement

In July 1969, I was 12 years old. As prize for winning a regional science fair, I traveled to Cape Canaveral to witness the launch of Apollo 11. To this day, the image of the towering Saturn V thrusting aloft on a pillar of flame and the accompanying thunderous roar that shook both the ground and my sternum remain vivid. Like flickering ghosts dancing across a closed eye after viewing a bright light, my memories of that historic day linger.

Following the launch, I raced back home to join my family crowding around a television set to watch the continuous coverage of the mission that culminated a few days later with the first manned landing on another celestial body. With multiple warning alarms sounding and with the steady assistance of copilot Buzz Aldrin, former naval-aviator-turned-astronaut Neil Armstrong made a perilous approach to a boulder-strewn field to land the Lunar Excursion Module (LEM) named Eagle with just seconds of fuel remaining.

With Armstrong’s words, “Houston, Tranquility base here. The Eagle has landed,” an anxious world breathed a sigh of relief. An estimated 600 million people—one-sixth the world’s estimated population of 3.6 billion people in 1969—watched or listened to the landing.

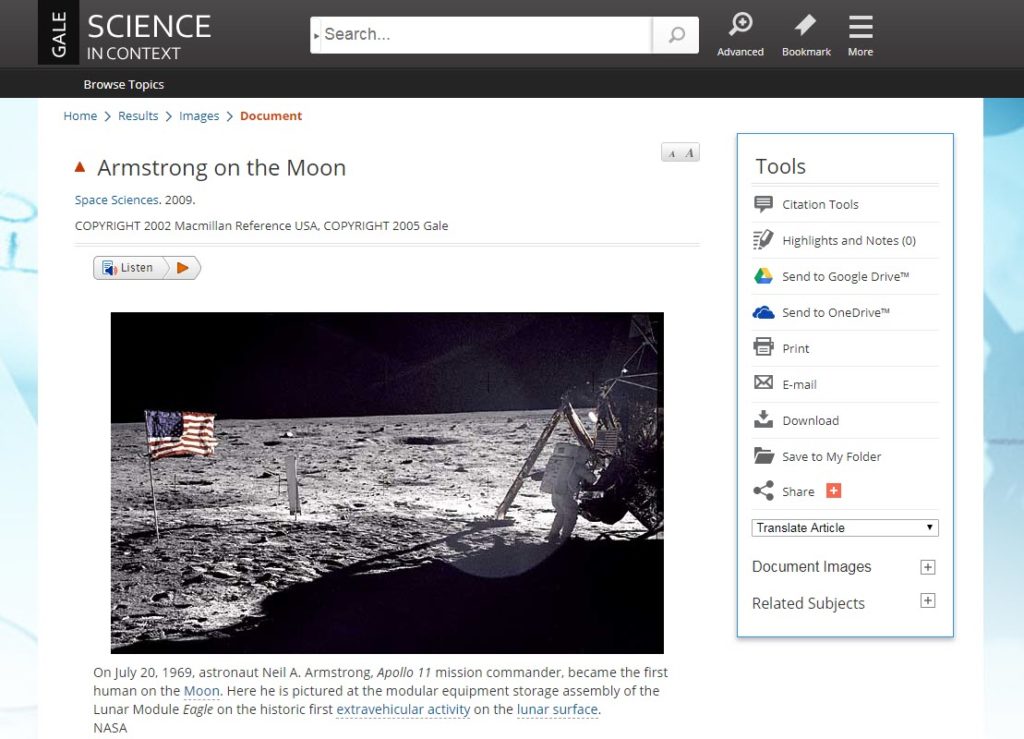

“Armstrong on the Moon.” Space Sciences, edited by Pat Dasch, Macmillan Reference USA, 2009. Science In Context, http://link.galegroup.com/apps/doc/CV2210047778/SCIC?u=gale&sid=SCIC&xid=bdb53bd1.

Restless, the astronauts advanced their schedule and just six hours later, Armstrong cracked the hatch, deployed a remote television camera, climbed down a ladder, paused for a few seconds on an LEM landing pad, and then made a historic footprint on the lunar surface.

The world heard Armstrong say, “That’s one small step for man; one giant leap for mankind.” Whether he flubbed the line and omitted an “a” before “man,” or as NASA later claimed, static obscured the transmission, is really unimportant. Armstrong’s intent, he later insisted, was to compare and contrast a small event (his step) with a monumental achievement in human history. Monumental it was, and so it shall forever remain.

The race into space and to the moon was fueled by Cold War passions where technological achievements were cast in contrasting ideological frames. With Michael Collins tracing a solitary orbit in Command Module Columbia above, American astronauts claimed victory over the Soviet Union by planting the flag of the United States in the Moon’s arid Sea of Tranquility.

America was, however, also gracious in the moment of conquest—a plaque placed on the moon made the achievement more inclusive and timeless by reading, “Here men from the planet Earth first set foot upon the Moon. July 1969, A.D. We came in peace for all mankind.”

Across fields of science, technology, and exploration, humankind has made significant advances since 1969. In terms of our realization of our collective humanity, we’ve taken many steps forward and some, regretfully, back.

For a brief time, a half-century ago, Apollo 11 drew families, nations, and people of wide diversity in color, language, and culture together to celebrate a milestone in human history. Upon that legacy of unity—our ability to set aside our differences, emphasize our commonality, and do things for all mankind—the fate of Earth and our continued exploration of space may depend.

For more information about the 1969 moon landing, Neil Armstrong, and much more, please visit Science In Context. Not a Science In Context subscriber? Request a trial today!

Meet the Author

K. Lee Lerner is a writer, editor, and aviator who, along with Brenda Wilmoth Lerner, is the editor of the Gale Encyclopedia of Espionage, Intelligence, and Security; Climate Change In Context; and many other award-winning books and articles on science, technology, and a range of global issues. A full bio and list of his work may be found at https://scholar.harvard.edu/kleelerner and https://harvard.academia.edu/KLeeLerner/.