On October 20, 2025, the first glow of Diwali—also called Deepavali, from the Sanskrit for “row of lamps”—will flicker to life in homes from Mumbai to Melbourne, and Madurai to Minneapolis. The festival usually falls on the new moon in Kartika, the Hindu lunar month corresponding to October or November in the Gregorian calendar. The holiday’s exact date changes year-to-year.

In the high school classroom, Diwali shows students how a tradition can take many forms. Its Hindu, Jain, and Sikh observances—and the ways diaspora communities adapt the holiday—underscore how celebrations mirror the histories and values of those who keep them. For students who celebrate Diwali themselves, having that tradition acknowledged in class can be just as powerful, affirming that their story belongs in the shared narrative of the school community.

When it comes to exploring a tradition as complex and far-reaching as Diwali, you can depend on Gale In Context: High School to support your students’ learning. The Diwali topic page hosts a collection of trustworthy and perspective-diverse historical sources, scholarly commentary, and contemporary perspectives. With these resources, learners can follow the festival from its earliest mentions in epic literature to the lamp-lit streets of Leicester and Singapore.

Diwali in Jainism and Sikhism

Though Jain and Sikh communities connect Diwali to different events, both associate light with liberation—spiritual for Jains, communal for Sikhs. This shared symbolism connects their traditions to the broader Festival of Lights, even as the stories themselves diverge.

We’ll give an overview of Jain and Sikh Diwali observances before turning to the Hindu celebrations, the most widely practiced version worldwide.

Jain Traditions

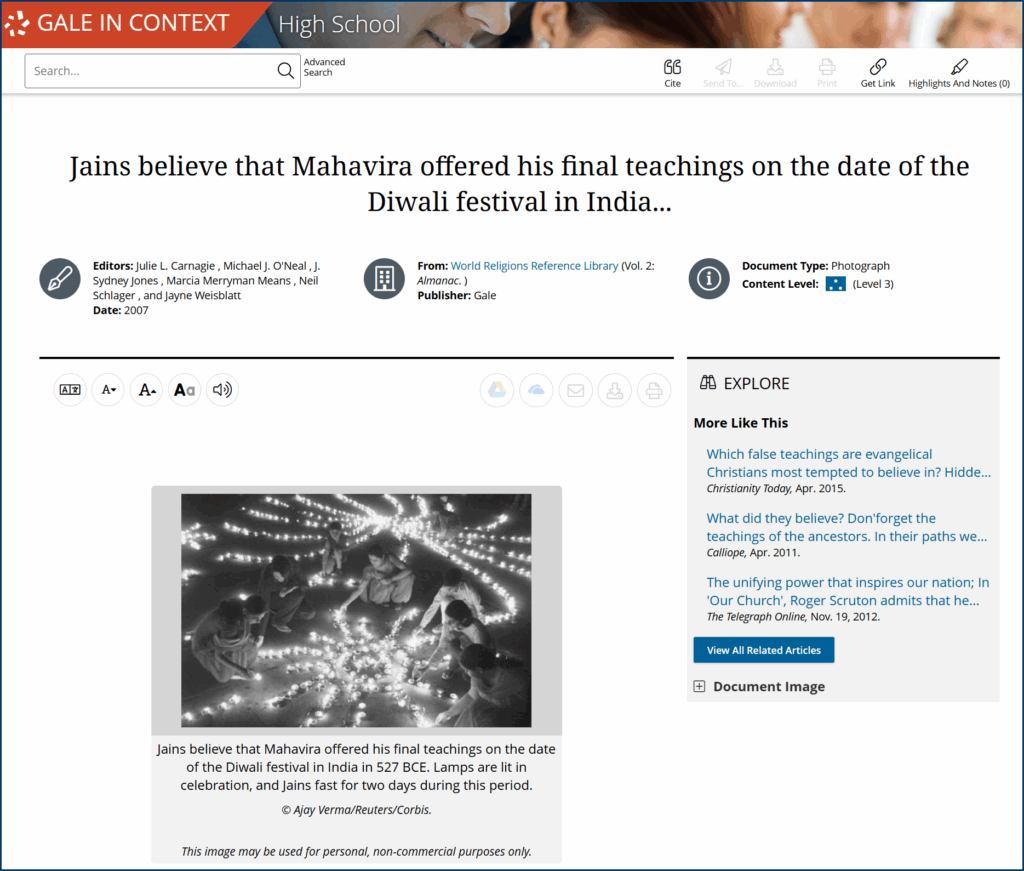

For Jains, Diwali commemorates the nirvana—a state of complete spiritual freedom, known in Sanskrit as moksha—of Lord Mahavira, the 24th and last spiritual teacher (Tirthankara) of the Jain faith. Mahavira attained this liberation in 527 BCE at the town of Pavapuri, ending the cycle of birth, death, and rebirth. The Jain traditions say that on the night of Lord Mahavira’s ascension, the gods lit up the darkness with countless lamps to honor his passing into eternal bliss.

In honor of Mahavira, followers see Diwali as a time to renew their commitment to ahimsa, the principle of complete nonviolence toward all living beings, and set aside time for meditation and self-discipline. Jain communities also gather for readings from sacred texts such as the Kalpa Sūtra.

Sikh Traditions

Diwali coincides with Bandi Chhor Divas for the Sikhs, known as the “Day of Liberation.”

In 1619, Guru Hargobind secured his release from imprisonment in Gwalior Fort, insisting that 52 detained princes be freed alongside him. Accounts describe him wearing a cloak altered with fifty-two trailing strips of cloth, each held by one of the princes as they walked free from the fort. Guru Hargobind returned to Amritsar to find the city already glowing with Diwali lamps, its residents having lit the Golden Temple to honor his commitment to justice and mercy.

Today, Sikh communities illuminate their gurdwaras, or “gateways to the Guru,” which serve as both religious and community centers. Inside, people gather to read and sing from the Guru Granth Sahib, the Sikh holy scripture. They then open their doors to host the langar—a free communal meal open to everyone, regardless of background or faith—in an act of seva, the Sikh value of service to others.

Hinduism and the Five Days of Diwali

In Hindu traditions, Diwali is a five-day festival rather than a single night. Each day emphasizes a different relationship—between people and the divine, within families, and across communities—yet all are joined by the theme of light overcoming darkness.

Although there are regional variations across groups of Hindu people, these summaries give a general idea of how communities celebrate the five days of Diwali.

Day 1 – Dhanteras

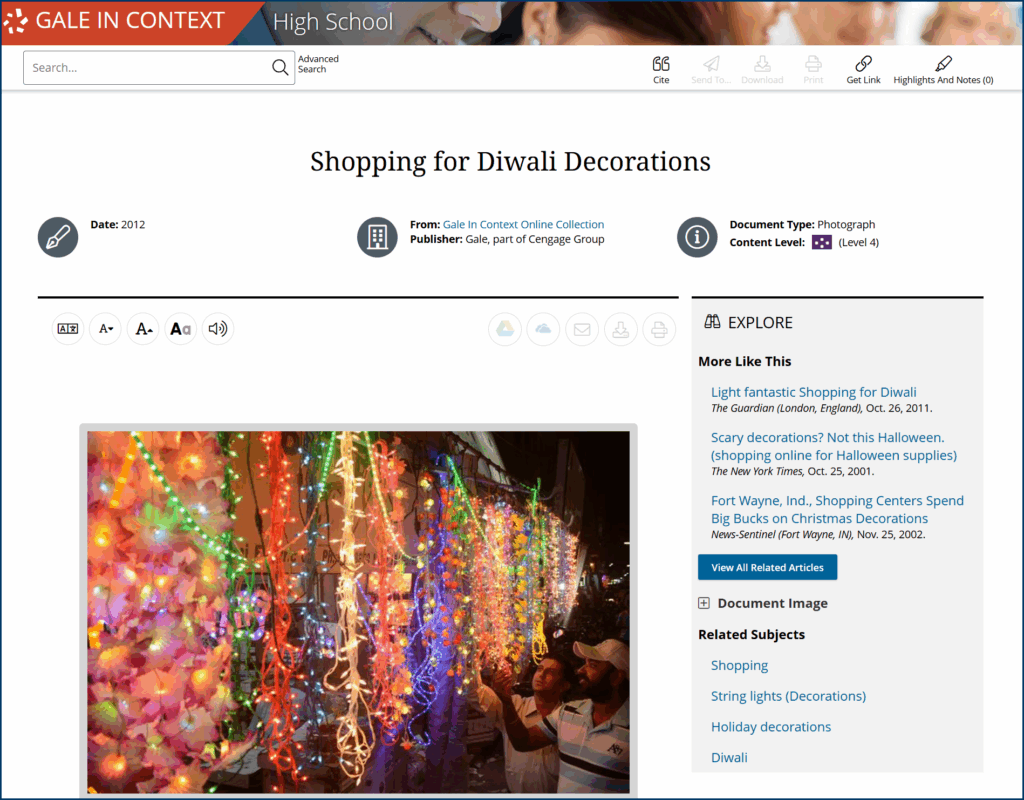

Families spend the days before Diwali scrubbing floors, repainting walls, and hanging bright decorations. The work is done with Lakshmi in mind—the goddess of wealth is said to favor clean, well-lit homes, and her visit is believed to bring prosperity in the year ahead.

In cities like Delhi and Mumbai, gold bangles, silver coins, and brass lamps fill stalls as customers follow the tradition of buying new metal goods for prosperity. They also prepare shakkarpare, crispy, sweet dough squares, or mathri, flaky, savory crackers, to serve with spiced tea when neighbors stop by after temple visits.

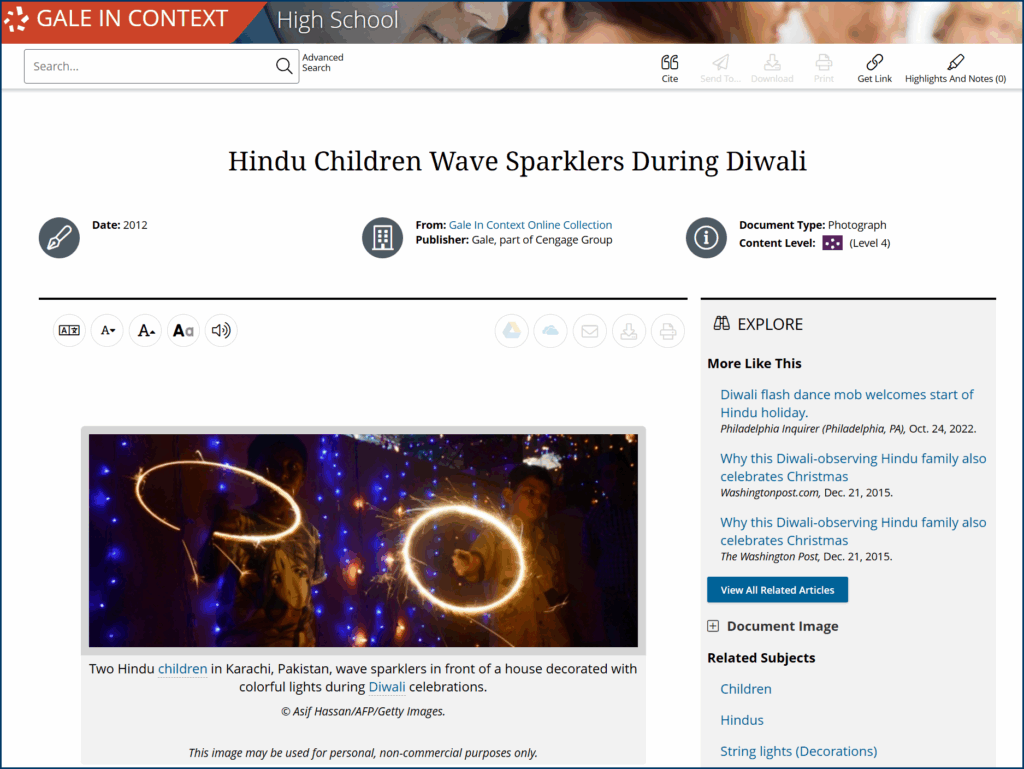

The evening sees families lining windowsills and thresholds with diyas—small clay lamps filled with oil and a cotton wick—fed by ghee or mustard oil, inviting Lakshmi into their homes with their warm light.

Day 2 – Naraka Chaturdashi (Choti Diwali)

In northern India, Naraka Chaturdashi celebrates the return of Lord Rama and Queen Sita to Ayodhya in the Ramayana, triumphant after defeating Ravana, the demon king. To guide Rama and Sita back, the cities and villages lit rows of diyas, a tradition still practiced in the lamp displays of Diwali today.

In much of southern India, the second day recalls the story of Lord Krishna killing the demon Narakasura and freeing the captives he held, a victory seen as cleansing evil and restoring harmony.

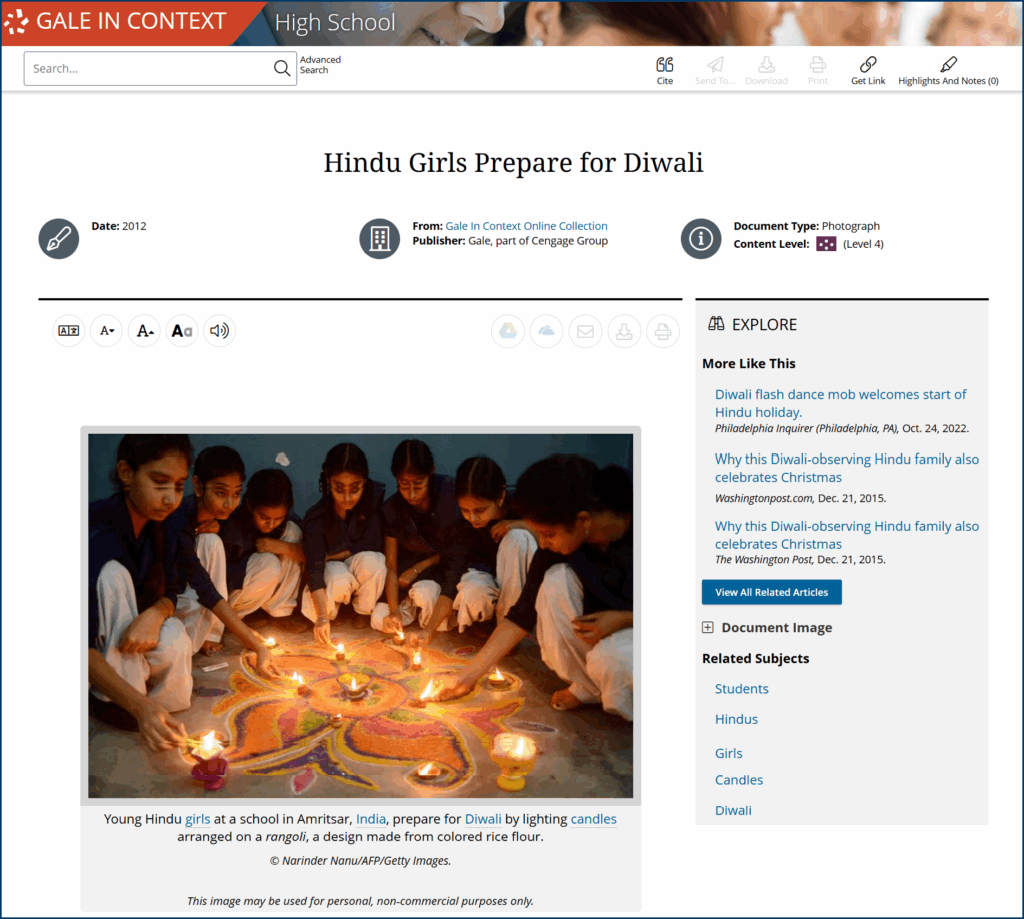

Before sunrise, households prepare with an oil bath, working warm sesame or coconut oil—sometimes scented with turmeric, neem, or local herbs—into their skin. Doorways are dressed with torans, hanging garlands of marigold or mango leaves, and courtyards come alive with rangoli: colorful designs traced in dyed rice flour or flower petals.

Day 3 – Diwali (Main Festival Day)

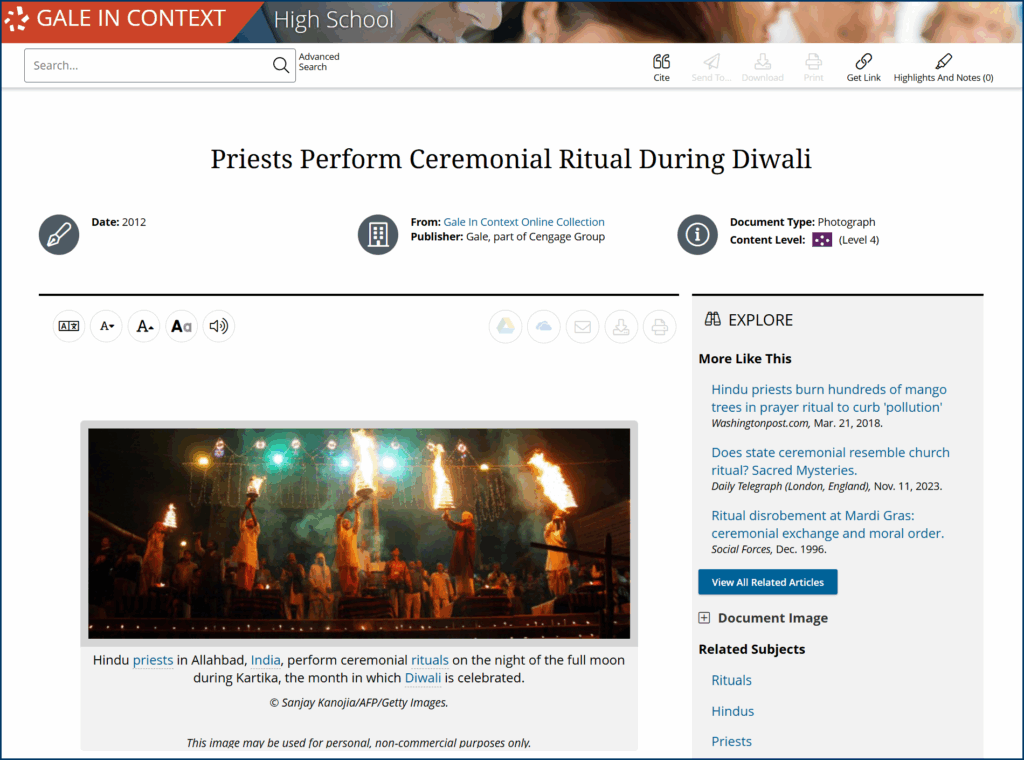

The third day falls on the new moon, making every source of light blaze brighter—from the rows of diyas flickering on balconies to the strings of jhalar lights draping rooftops. Families gather for Lakshmi Puja, offering the goddess plates of sweet laddoos, cardamom-scented rice pudding called kheer, and garlands of lotus buds.

In Bengal, many households also honor Kali, the fierce goddess of time and change, often associated with both destruction and the protection of devotees. Altars to her blaze with hundreds of lamps as cities erupt in fireworks: rockets arc into chrysanthemums of color, while anar—cone-shaped firework fountains—hiss showers of sparks.

Day 4 – Govardhan Puja (Annakut)

Govardhan Puja honors the story of Lord Krishna lifting Mount Govardhan to shield villagers from a storm sent by the god Indra. To commemorate the event, temples and homes construct “mountains” of food—towering displays of puri (deep-fried bread), spiced rice, slow-cooked lentils, seasonal vegetables, and dozens of mithai (traditional sweets).

In Gujarat, Annakut—literally “mountain of food”—offerings can include more than a hundred distinct dishes, from tangy undhiyu, a slow-cooked winter vegetable medley, to sweet shrikhand, saffron-infused yogurt. Devotees circle the food in prayer before sharing it in a communal feast.

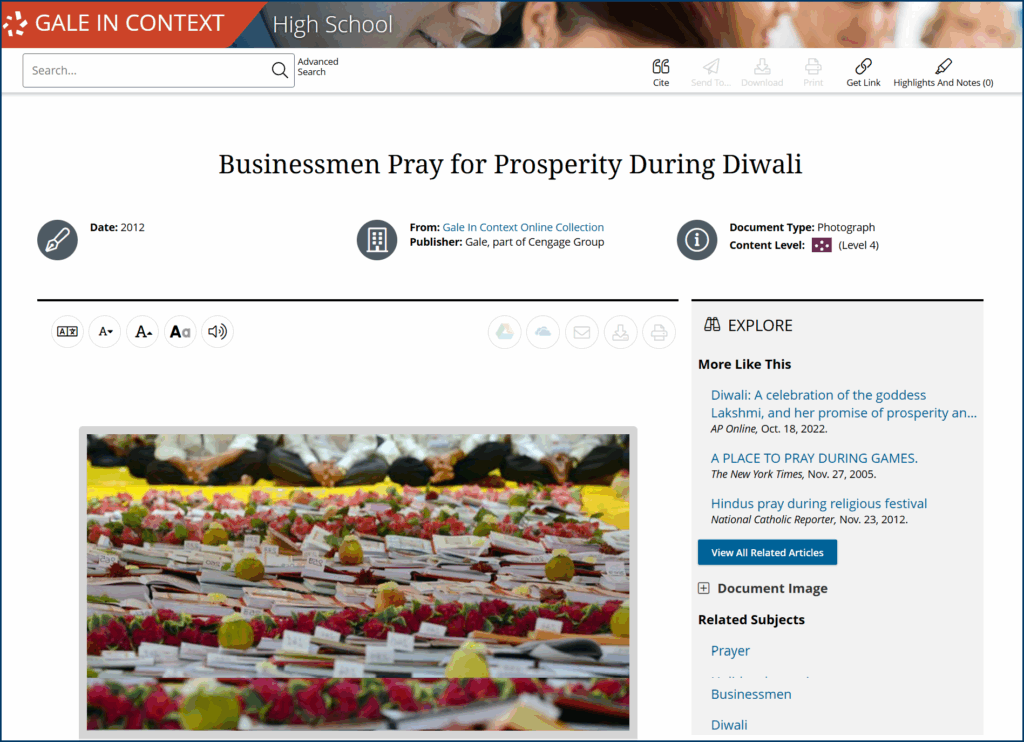

In the business districts of northern India, shopkeepers close their ledgers, decorate them with fruit, flowers, and red kumkum—a powdered pigment used in Hindu rituals—and open new books with prayers for the year’s prosperity.

Day 5 – Bhai Dooj

Bhai Dooj, the final day of Diwali, centers on the relationship between brothers and sisters. Sisters welcome their brothers with an aarti—a blessing performed with a small lamp—then press a tilak, or red mark, onto their foreheads to wish them health and long life. Brothers give gifts in return, and the visit often ends with a shared meal. Many extend the tradition to cousins or friends, using the occasion to affirm mutual care and responsibility.

Diwali in the Diaspora

Wherever Indian communities have settled, Diwali has taken root, carrying familiar rituals into new landscapes. In many cities, the festival arrived alongside waves of migration, and has grown into a public expression of cultural identity, filling public squares with light and inviting neighbors of every background to share in the festivities.

Leicester, United Kingdom

In the decades after the mid-20th century, many families of Indian origin settled in Leicester—especially during the 1970s, when Idi Amin’s regime in Uganda expelled thousands. They revitalized declining neighborhoods, and brought traditions like Diwali into public life.

Leicester’s Belgrave Road, known as the Golden Mile, hosts Britain’s largest Diwali celebration. What began in 1983 as a modest community lighting has grown into a civic spectacle drawing tens of thousands.

Weeks in advance, illuminated arches patterned with lotus flowers and fireworks span the street. At the official lighting ceremony, Belgrave Road fills with music, food stalls sell jalebi and pani puri, and visitors move between the Diwali Village fair, temple prasad offerings, and the fireworks finale over the city.

New York City, United States

South Asian migration to the US increased sharply after the 1965 Immigration and Nationality Act removed discriminatory quotas. Queens—especially Jackson Heights—quickly became a center for Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi, and Nepali communities.

Broadway between 46th and 48th Streets hosts “Diwali at Times Square,” a day-long event that blends South Asian cultural performance with the energy of one of the world’s most famous intersections. Since its founding in 2013, the festival has featured music and dance acts, vendor booths, and appearances by city leaders.

Brisbane, Australia

From the 1970s onward, changes to Australian immigration policy and demand for skilled labor opened the door to South Asian professionals and students. Brisbane’s growing Indian community has used public events to make Diwali both a cultural exchange and a community celebration.

In Brisbane, the Federation of Indian Communities of Queensland hosts the Diwali Indian Festival of Lights in King George Square. The celebration fills the city center with rangoli art, light displays, music, and dance performances, alongside stalls serving traditional vegetarian dishes and sweets.

Chaguanas, Trinidad and Tobago

Between 1845 and 1917, more than 140,000 Indians arrived in Trinidad under the British indenture system. The descendants of those newcomers now form an integral part of the population, and Diwali has been a national holiday since the 1960s.

Divali Nagar (Divali Village) has been the centerpiece of Trinidad’s national Diwali celebration since the 1980s. Hosted by the National Council of Indian Culture in Chaguanas, the nine-night event combines cultural showcases, craft vendors, and food stalls with nightly lamp-lighting. The open-air stage features chutney music, dance competitions, and theater, while the fairgrounds offer local snacks like pholourie alongside traditional Indian sweets.

Explore How Diwali Connects Communities Worldwide

In an interview with NPR, chef and cookbook author Anupy Singla shared what the holiday means to her: “Diwali is about lighting a candle, not just physically, but also internally, so lighting this flame inside you to go from darkness into light . . . You’re seeking to be more knowledgeable and to give up grudges from the year past, to kind of move and look ahead to a new year.”

With Gale In Context: High School, you can bring that spirit into your classroom as students seek more knowledge about Diwali’s history, stories, and modern celebrations through credible sources that engage and immerse learners.

Request more information about the ways that Gale In Context: High School connects your students with a multicultural world by contacting your local Gale sales representative.