| By J. Robert Parks |

The relationship between the federal government and the First Nations in the Dakotas has been one of broken treaties, neglect, and systematic oppression. One of the most infamous events was the Massacre at Wounded Knee in 1890. Fifty years ago this week (on February 27), another confrontation began at Wounded Knee. Known by some as the Occupation of Wounded Knee and by others as the Siege of Wounded Knee, it pitted members of the American Indian Movement against U.S. marshals and FBI agents for 71 days. Teachers and librarians who want to help students understand the complex interactions between Native Americans and the federal government will find numerous resources in Gale In Context: U.S. History.

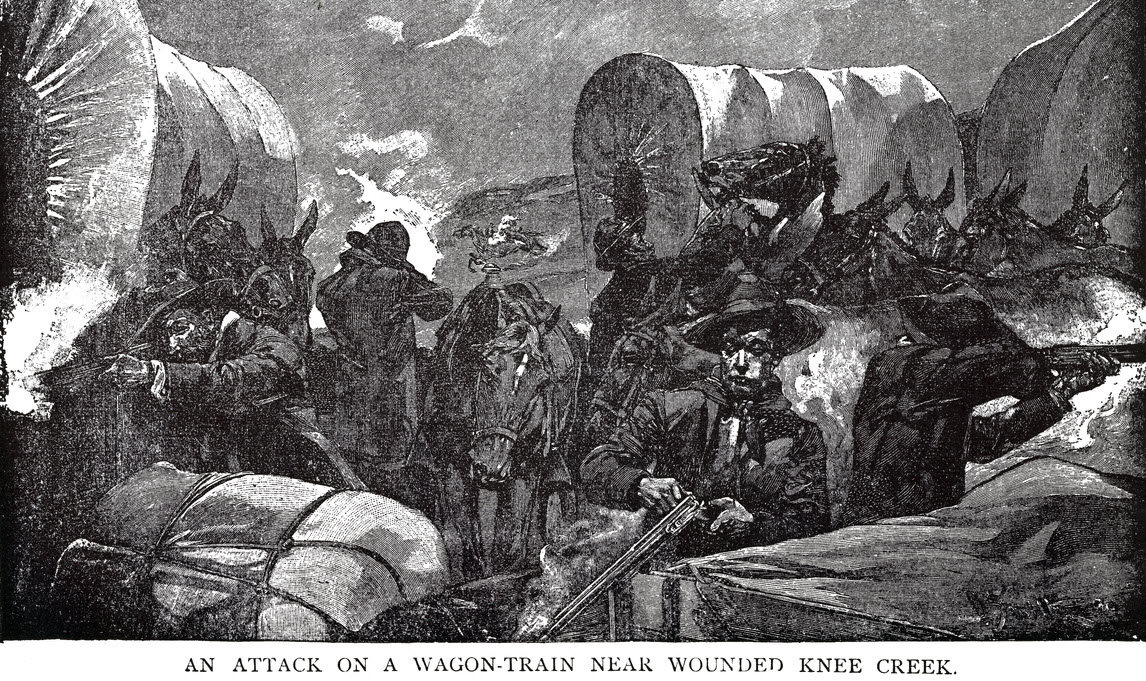

The Wounded Knee Massacre was the culmination of the Plains Wars, a decades-long fight in which the federal government pushed the Native American peoples off their lands and onto reservations. Although the fighting was mostly over by 1880, the federal government reneged on many of the agreements it made. Furthermore, the Native peoples struggled on the reservations, as the land was often poor for agriculture and hunting. Many Native Americans turned to the Ghost Dance movement as a way of reviving their culture. The federal government, however, feared that it would cause a revival of the fighting. To prevent that, it assassinated Sitting Bull and then, at Wounded Knee, attacked the group led by Spotted Elk, killing approximately 400 of his followers―many of them women and children.

The decades that followed were grim ones for many First Nations. The federal government routinely denied their sovereignty and stripped the people of their land and rights. Finally, in the mid-twentieth century, Native Americans began to organize and demand the government abide by the treaties they had signed. Various Native organizations formed to push for more resources and better conditions on the reservations. As with many protest movements, some Native organizations were moderate and were content with incremental progress. Other organizations, however, demanded a more militant approach.

One of the most controversial of those was the American Indian Movement (AIM). It was formed in 1968 by Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt, and it modeled itself on the Black Panthers. It wanted to monitor the police and keep track of the abuses of civil liberties against Native Americans, as well as offer service programs such as alternative schools and low-cost housing. In 1972, the organization strove to become a national movement, and it organized a protest caravan called the Trail of Broken Treaties, which traveled across the United States. The protest ended in Washington, DC, without a clear endgame. The protestors had nowhere to stay and took shelter in the Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) building. A confrontation with police led AIM to occupy the building for a week. Although that was unplanned, it brought the group considerable press, much of which was negative.

The Occupation of Wounded Knee, which happened the following year, grew out of a local dispute. Richard Wilson had been accused of buying votes to become president of the Oglala Lakota tribal council on the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. While in power, he threatened his opponents and allegedly mishandled government funds. The Department of Justice later said his presidency was a “reign of terror.” The BIA supported him, however, because he didn’t allow protests on the reservation, and it even sent agents to support him.

Angry members of the Oglala Lakota tribe reached out to AIM for assistance. When AIM member Russell Means, who had promised to run against Wilson, came onto the reservation, he was beaten by some of Wilson’s men. Means later returned with 250 Native Americans and took over the village of Wounded Knee—armed, police said, with weapons and ammunition they had stolen from a reservation store. Means apparently did not plan to stay long and only wanted to negotiate for Wilson’s removal, but government forces blocked the roads coming out of Wounded Knee, leading to the occupation/siege.

The standoff lasted for 71 days. Means and his supporters set up defenses and barricades, and the two sides routinely exchanged gunfire. Two Native Americans were killed and a dozen badly wounded. Support for the occupation by AIM grew on other reservations, and some Native Americans tried to come to Wounded Knee to offer their support. The federal government finally agreed to discussions with the Oglala leaders, and the occupation ended peacefully, but the disputes between AIM and the BIA continued for years.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale In Context: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.