| J. Robert Parks |

Through the benefit of hindsight, historic events can look much different for generations far removed from the time in which those events occurred. Teachers can readily give examples of that for every era. The Compromise of 1850 is a particularly notable instance in U.S. history, however. Although the legislation was hailed as a way to solidify the Union, it merely ended up contributing to a reckoning over slavery that was a foundational aspect of the ultimate Civil War. This week is the 175th anniversary of the Compromise of 1850, which was agreed to on September 9. Educators and librarians wanting to help students grasp both the events leading up to the compromise and its consequences will find numerous resources in Gale In Context: U.S. History.

The first 70 years of the United States featured a number of compromises over slavery. From the Constitution, which avoids using the word “slave” yet features numerous protections for enslavers, to the Missouri Compromise of 1820, to the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, Congress had to confront the issue of slavery at every point the country wanted to expand. The slave states wanted to protect their power, but over time the growing abolitionist movement in the North pressured northern politicians to prevent slavery’s spread.

Henry Clay was a legislator at the center of both the Missouri Compromise (for which he earned the nickname the Great Compromiser) and the Compromise of 1850. He was born in 1777 and was an enslaver in Kentucky, but he also believed in the country’s expansion and worked to keep the Union together. He was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives in 1811 and immediately became the Speaker of the House. It was in that role that he helped negotiate the Missouri Compromise that brought Maine and Missouri into the Union (Maine as a free state, Missouri as a slave state). The Missouri Compromise established the 36°30’ parallel as the northern limit of slavery, but it also set the precedent that incoming states had to be balanced between free and slave states.

Those agreements became particularly relevant after the Mexican–American War ended in 1848. California wanted to enter the Union as a free state, which would upset the balance of slave and free states. Those living on or moving to land that the United States had seized from Mexico would eventually seek statehood recognition as well. Anticipating that, in 1846, Pennsylvania Rep. David Wilmot tried to commit Congress to prevent the expansion of slavery into the former lands of Mexico. Congress didn’t agree to that provision, but it indicated how abolitionists were becoming more insistent in stopping slavery from spreading beyond the South.

By 1850, Henry Clay was a U.S. senator, and he pushed for a grand compromise. California would enter as a free state, and in addition the slave trade would be banned in Washington, D.C. (slavery would still be legal in the nation’s capital). Furthermore, the federal government paid Texas $10 million to give up some of its land, which would later become Utah and New Mexico, and those lands had no restrictions on slavery. The most contentious part of the compromise, at least for abolitionists, was an amendment to the Fugitive Slave Law. Now, not only could enslavers try to recapture enslaved people who had escaped, but the federal government and even individual citizens had to assist in the recapture. Those who helped enslaved people escape were subject to harsh penalties.

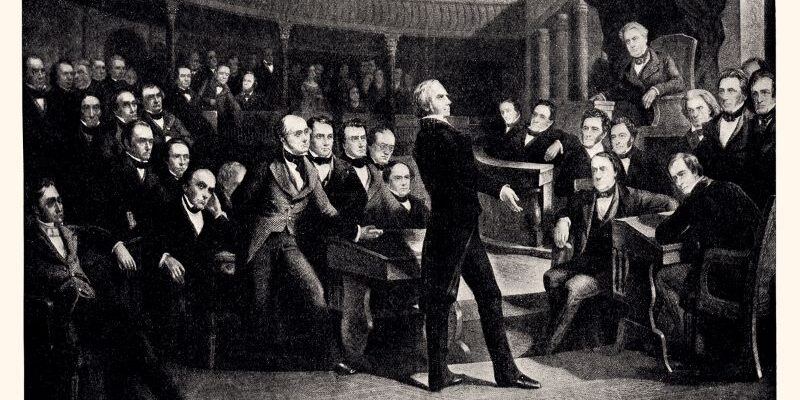

In arguing for the compromise, Clay made a speech before Congress in which he tried to convince southern legislators that staying in the Union provided a greater likelihood that slavery would continue. He then went on to make an impassioned defense of the Union and against secession of any kind, arguing that it would certainly precipitate a war. Clay and his supporters carried the day.

Although Clay saw the legislation as an important step toward sustaining the Union, the impact of the compromise and especially the amendment to the Fugitive Slave Act was to create an even deeper national divide. Many northerners were outraged at the idea that they had to participate in returning enslaved people who had escaped. Four years later, the Kansas–Nebraska Act of 1854 had the effect of repealing the Missouri Compromise and inflaming tensions even more. Barely a decade after the Compromise of 1850, the country was hurtling toward war, despite any hopeful motivations of Henry Clay to avoid it.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale In Context: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.