| By J. Robert Parks |

Imagine you’re watching a quiz show, and the category “4th Century Events” pops up on the screen. How confident are you that you’re going to be able to get the answer? You might guess in the category for Rome, deeming it will be an easier question. If you remember a little from your Western Civilization class, you might buzz in with Constantine at some point. But odds are that one of the answers will be the Council of Nicaea or the Nicene Creed. For it was 1,700 years ago this month that a group of 300 Christian bishops gathered to argue about the divinity of Jesus. Although that may not seem relevant to any but the Christian faithful, the history of the Council of Nicaea is significant for multiple reasons and not just religious ones. Teachers and librarians focusing on ancient history or religious education will find a wealth of resources in Gale In Context: World History to pass along to students.

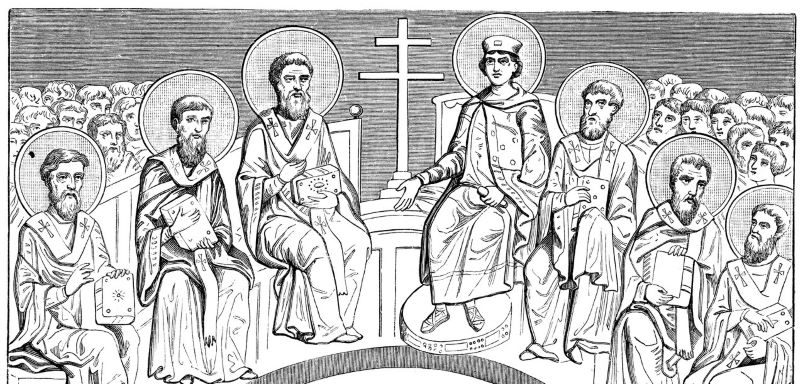

The Council of Nicaea was the first general assembly of the Christian church that gathered bishops from around the Roman world. It was called by Emperor Constantine I, who had formally ended the persecution of Christianity in 313 CE, by issuing what is now known as the Edict of Milan. Constantine wasn’t a Christian, but tradition states that he saw a vision of a cross in 312 when he was preparing for a battle against his brother-in-law Maxentius. The vision indicated that the symbol would lead him to victory, so he had his troops inscribe a cross on their shields. Constantine and his forces won. It is, of course, also possible that Constantine recognized that co-opting the growing Christian movement was a better political decision than persecuting the religious faithful.

The Council of Nicaea was called a dozen years later to resolve the growing controversy over Arianism. Arius was a prominent Christian thinker who argued that Jesus had not existed for all eternity but that only God the Father had. Furthermore, Arius argued that Jesus was divine but that his divinity was different from that of God the Father. Alexander, the bishop of Alexandria, called a synod of bishops from Egypt and Syria, who excommunicated Arius, but Arius continued to gain followers as he traveled throughout the Roman world. Constantine feared that the controversy would lead to greater division within the empire and he called the Council to prevent that.

The Council began on either May 20 or June 19, 325 CE, when approximately 300 bishops gathered at Constantine’s palace in Nicaea, in what is today northwestern Turkey. The argument over the Trinity and particularly the nature of Jesus involved terminology and distinctions that can challenge even the most theologically astute. Over the course of the summer, the Council debated, eventually rejecting Arius’s teaching and establishing what is now called the Nicene Creed.

If Constantine and the bishops hoped that the Council would put an end to the controversy, they were quickly disappointed. In some cases, Arian sympathizers continued to advocate for Arius’s teachings. In other cases, non-Arian bishops took issue with the Nicene Creed itself, arguing that its concept of homoousios, or consubstantiation, was incorrect. One of the pivotal defenders of the Nicene Creed and what became accepted Christian belief was Athanasius (he could easily be a difficult answer for the hypothetical “4th Century Events” category). Decades of theological arguing and political jockeying ensued, as the bishops argued against each other and endeavored to gain favor with Constantine and his successors.

Eventually, Emperor Theodosius I called for another council, this one known as the First Council of Constantinople in 381. At this council, the bishops affirmed the Nicene Creed and condemned various heresies. They also expanded the Nicene Creed to include more about the Holy Spirit, the third divine being of the Trinity. Other debates over the Trinity arose in the ensuing centuries, but the Nicene Creed is still widely accepted by the three major sects of Christendom—Catholic, Orthodox, and Protestant—and still recited in churches around the world every Sunday. The Council of Nicaea had another long-term effect. It set the precedent that political rulers had some control over Christian religious leaders and could even affect Christian doctrine. The struggle between religious and political leaders over who gets to define Christian faith and practice has continued ever since.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale InContext: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.