October’s second Monday marks the shared observance of Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day, providing elementary students an opportunity to examine both the spirit of exploration and the cultures that long predated it. Teaching these histories side by side gives students an early framework for understanding how the same moment in time can mean different things to different people and why both stories belong in the classroom.

Gale In Context: Elementary makes it easier to teach complex historical narratives in a way that young learners can understand. The platform brings together educator-vetted biographies, primary sources, images, and videos designed for young readers, making it easier to introduce unfamiliar ideas without oversimplifying them. Alongside trustworthy content, Gale In Context: Elementary supports a more inclusive classroom, with features such as read-aloud audio and built-in translation tools that ensure all students can participate fully, even if they approach the material with different strengths.

Teaching Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day together gives students multiple perspectives on the stories we celebrate each year on the second Monday in October. What follows is a review of helpful context and classroom-ready resources for both sides of the story, beginning with Christopher Columbus and the early age of European exploration, and continuing through Indigenous histories that long predate 1492 and remain vital today.

The Age of Exploration

Christopher Columbus has long been credited with “discovering” the Americas, but he was not the first European to reach them. His 1492 voyage, however, was the beginning of a sustained relationship between European nations and the “new world,” setting in motion centuries of cultural exchange and conflict.

Columbus’s first voyage in 1492 was part of a larger movement now known as the Age of Exploration—a period when European powers funded long-distance sea travel in search of new trade routes, territorial claims, and economic advantage. England, France, Portugal, Spain, and other nations sent expeditions across unfamiliar waters not only to expand their influence, but also to access valuable goods—such as spices, silk, and gold—that had traditionally traveled by land via routes controlled by other empires.

Earlier European Voyages to North America

Centuries before Christopher Columbus crossed the Atlantic, Norse sailors, known as Vikings, had already made contact with the North American coast. Around the year 1000 CE, Leif Eriksson sailed west from Greenland and reached a region he called Vinland, most likely corresponding to present-day Newfoundland. The Norse presence was brief and left little lasting trace, but archaeological evidence at sites like L’Anse aux Meadows confirms the early arrival.

Unlike Columbus’s later voyages, which established sustained contact between Europe and the Americas, Eriksson’s journey did not lead to long-term settlement or cultural exchange. However, it does complicate the idea that Columbus made “first contact.”

Who Was Christopher Columbus?

Christopher Columbus was born in 1451 in Genoa, Italy. As a young man, he worked as a sailor and merchant, gaining experience in navigation and sea travel. By the late 1480s, he had developed a plan to reach Asia by sailing west across the Atlantic Ocean—an idea that challenged existing trade routes controlled by land and sea powers in Europe and the Middle East.

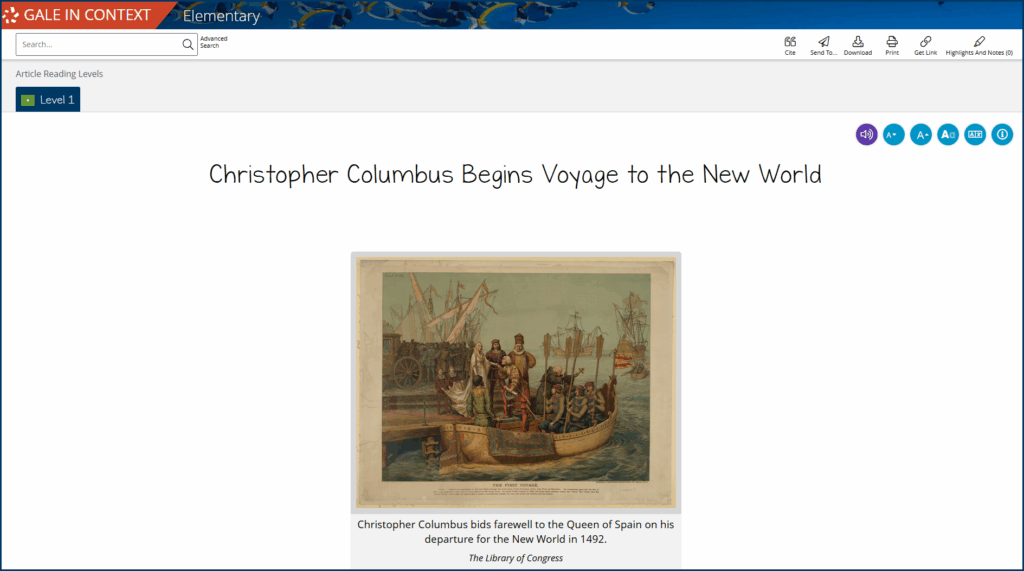

After several failed attempts to secure funding, Columbus gained support from King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella of Spain. In 1492, he set sail with three ships—the Niña, the Pinta, and the Santa María—on a voyage he believed would lead him to the East Indies. Europeans used this term to describe the islands of Southeast Asia, which were known for their spices and other trade goods.

What Did Columbus Actually Find?

Upon making landfall, Columbus believed he had reached Asia, but he had, in fact, arrived in the Caribbean, landing first on an island in what is now the Bahamas. Believing he had reached the East Indies, he called the local people “Indians,” and he described the landscape in his journals as rich with resources, including fertile soil, fresh water, and natural harbors. He also noted the absence of weapons among the people he encountered, which he interpreted—mistakenly—as a sign of their cultural simplicity and ease of conquest.

Over the course of four voyages, Columbus explored parts of the Caribbean as well as sections of Central and South America. Although he never found the spices or gold he hoped for, Columbus’s reports helped ignite further European interest, catalyzing a wave of transatlantic exploration and colonization. While these journeys expanded trade—both cultural and material—they also brought lasting consequences for Indigenous peoples, including displacement, disease, and the beginning of European control over Native lands.

How Do Schools Observe Columbus Day Today?

Columbus Day has been a federal holiday in the United States since 1937, originally established to commemorate the explorer’s first voyage and its impact on world history. For many decades, schools marked the occasion by teaching about Columbus’s life, his ships, and the idea of “discovery.”

In more recent years, however, many classrooms have broadened that focus, placing Columbus’s story alongside the perspectives of the Indigenous peoples whose lives were affected by European exploration and colonization. Columbus remains part of the curriculum, but there’s a growing understanding that our appreciation of historical events can be enriched by introducing perspectives that have been missing from the narrative.

Indigenous Peoples’ Day: The Story of the Americas Before and Beyond Columbus

The word Indigenous refers to the original peoples of a place—those whose ancestors have lived on the land for thousands of years.

In the Americas, Indigenous peoples encompass a diverse range of communities and nations, each with its own unique language and way of life. In what is now the United States, this includes groups such as the Cherokee, Lakota, Navajo, and many others.

Indigenous Histories in the Americas

For centuries before European explorers knew what lay on the other side of the ocean, Indigenous peoples lived across the Americas, from the Arctic Circle to the tip of South America.

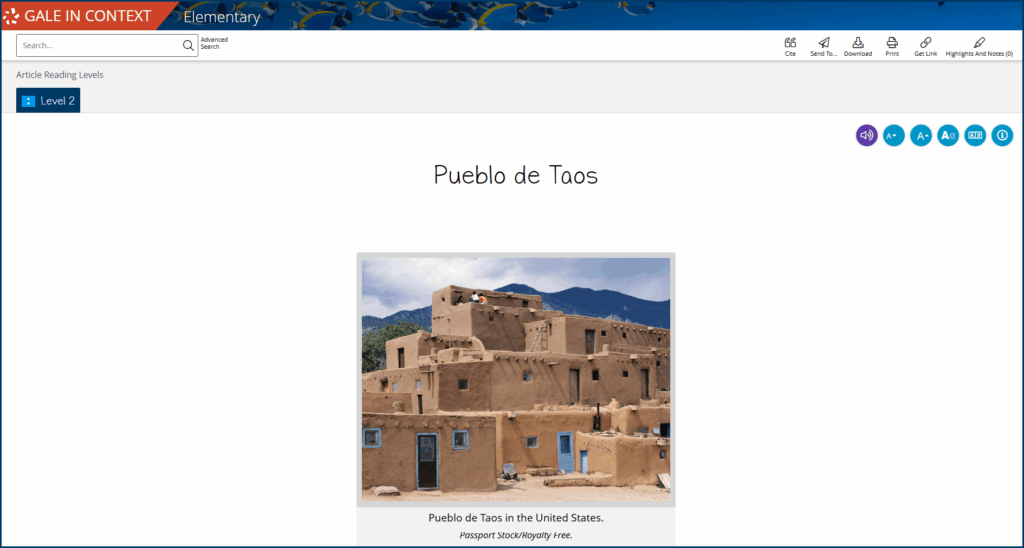

In the United States, their histories are vast and varied. The Mississippians constructed mound cities along riverbanks, establishing complex trade and ceremonial networks that spanned large regions. In the Southwest, Pueblo communities constructed multi-story dwellings from stone and adobe, many of which remain standing today.

As early as the twelfth century, the Haudenosaunee Confederacy of the Northeast formed a political alliance of the Cayuga, Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Seneca, and later, the Tuscarora, who worked together under The Great Law of Peace. This early example of a constitution saw representatives from each nation coming together for collective decision-making and dispute resolution through discussion rather than force. It maintained peace among member nations for centuries and was so effective that it influenced the structure of American democracy.

These are just three examples among the approximately 574 federally recognized American Indian and Alaska Native groups that developed their own languages, belief systems, and economies. This deep-rooted presence is part of why Indigenous Peoples’ Day is observed on the same date as Columbus Day. It acknowledges that the story of the Americas didn’t begin with European exploration and invites students to learn about the cultures and nations that were already thriving when Columbus arrived.

To help students connect Indigenous communities to specific places, learners can use Gale In Context: Elementary’s extensive collection of resources on Indigenous groups to learn about the tribal nations historically tied to different parts of the U.S. Encourage them to select a mix of local tribes and groups from other regions so students can explore the diversity of cultures across the Americas.

Examples of these tribes include:

- Northeast: Wampanoag

- Southeast: Chickasaw and Choctaw

- Great Lakes: Ojibwe (Chippewa) and Menominee

- Plains: Cheyenne and Arapaho

- Southwest: Navajo (Diné) and Apache

- Pacific Northwest: Chinook and Tlingit-Haida

- California: Chumash

- Alaska and Arctic: Aleut (Unangan)

- Hawaii: Kānaka Maoli (Native Hawaiians)

As they work, ask learners to consider questions like:

- Where does this nation live now, and where did they live traditionally?

- What are some important cultural traditions, values, or ways of life that continue today?

- What is one contribution this group has made to American history, culture, science, or the environment?

Celebrating Indigenous Peoples’ Day

Indigenous Peoples’ Day was first formally recognized in 1992 by the city of Berkeley, California, on the 500th anniversary of Columbus’s first voyage. The holiday has since grown as communities across the country host events that pay homage to Native culture through parades, performances, museum programs, and hands-on activities.

Including these celebrations in your lessons on Indigenous Peoples’ Day gives students a chance to see that these cultures are living and evolving, rather than relics of the past.

First Americans Museum – Oklahoma City, OK

The First Americans Museum hosts a full day of Indigenous Peoples’ Day programming, including stickball games, traditional dancing, storytelling circles, and community art activities. Visitors are welcome to join in these hands-on demonstrations led by tribal elders and educators.

Indigenous Peoples’ Weekend at the Museum of the American Revolution – Philadelphia, PA

On the weekend before Indigenous Peoples’ Day, the Museum of the American Revolution invites the community to join in a variety of activities led by Indigenous groups from the region. Last year’s events included Lenape social dances, a Wampum belt craft tutorial, and a core exhibition on the Oneida Nation.

Indigenous Peoples Sunrise Ceremony – Alcatraz Island, San Francisco, CA

This early morning event, organized by the International Indian Treaty Council, brings thousands to Alcatraz Island for a sunrise gathering on Indigenous Peoples’ Day and Thanksgiving. The ceremony honors the 1969–71 occupation of the island by Native activists and draws attention to ongoing struggles for Indigenous sovereignty.

Teaching History Through Multiple Voices

For many elementary students, observing Columbus Day and Indigenous Peoples’ Day together may be the first time they’ve been invited to consider the past from more than one perspective.

Gale In Context: Elementary offers a robust collection of articles, videos, photos, and more to support those early conversations. Designed specifically for young learners, the platform allows students to safely explore timely topics when curiosity strikes.

Contact your Gale sales representative to schedule a demo or learn more about how Gale In Context: Elementary empowers your students with the tools to answer their questions about the world around them.