| By Dr. Bequita Pegram |

In addition to teaching U.S. history and digital storytelling, I host a podcast called “D.O.P.E. Conversations.” I do it for one very important reason: to invite theorists and researchers to break down their research in a way that grassroots efforts can use. Sometimes scholars lose focus of the idea that our work is not just for a conference or a journal—it’s really to help everyday people. We have to make our work tangible. My mission is to make history enjoyable and to democratize access to knowledge, empowering the next generation of researchers, storytellers, and change-makers.

One way for instructors to make history engaging and tangible is to leverage media-rich digital archives and data analysis tools in our teaching and research. During the recent Hacking History Digital Humanities Skills Workshop hosted by Gale and Loyola University Chicago, University Libraries, I had the opportunity to use Gale Digital Scholar Lab’s (the Lab’s) data visualization and analysis tools to mine primary source texts and build content sets as part of a research group that uncovered some fascinating insights about the abolitionist movement.

My group and I compared the differing sentiments towards slavery in the U.S. and UK. The UK ended slavery much earlier than the U.S. did, and we asked, “What may have been the driving force?” We knew that churches played a role in abolition, so we looked at sermons from the UK and U.S. in the Gale Primary Sources archive Slavery and Anti-Slavery to better understand their influence.

McCaine, Alexander, and Methodist Protestant Church . General Conference Baltimore, Md.). Slavery defended from Scripture, against the attacks of the abolitionists : in a speech delivered before the General Conference of the Methodist Protestant Church, in Baltimore, 1842. Baltimore, United States: Printed by W. Wooddy, 1842. Slavery and Anti-Slavery: A Transnational Archive (accessed April 7, 2025). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/DS0100211976/SAS?u=gale&sid=bookmark-SAS&xid=3a55c3ab&pg=3.

First, we used the Lab’s Ngrams visualization tool to reveal the words most commonly found in sermons during that time. Then we looked at the Sentiment Analysis tool. That was my favorite visualization because it showed that sermons in the UK had a negative sentiment around the word “slavery,” while sermons in the U.S. from around the same period showed a positive sentiment. My group and I thought that was very impactful, and we agreed to continue our investigation to dig deeper into the sermons and even examine public sentiment in newsletters or brochures at the time. How did abolitionists themselves respond to the sermons? Did they think the Church should have been involved? How did information spread between the UK and U.S.? It’s a fascinating area of research, made possible by the Lab and the digital humanities tools it offers researchers.

I plan to use Gale Digital Scholar Lab and Gale Primary Sources with my undergraduate students. Exposing undergraduates to these advanced digital research tools early in their academic paths can help prepare them for higher-level work, including graduate school. With the Lab, students don’t need graduate-level statistics and data analysis courses. Research is more accessible, helping students see themselves capable of potentially pursuing graduate research work someday.

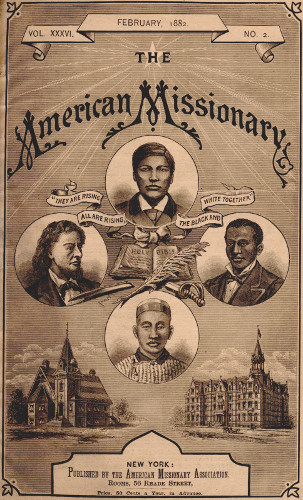

“The American Missionary — Volume 36, No. 2, February, 1882.” The Project Gutenberg eBook of the American missionary — volume 36, no. 2, February, 1882, by various., July 5, 2018. https://www.gutenberg.org/files/57446/57446-h/57446-h.htm.

Giving students access to these kinds of digital archives and tools creates empowerment, and empowered students learn more deeply. I saw this idea in action recently when I had my U.S. History students create documentaries as part of a class project where they researched their genealogy using Ancestry.com. Some of these projects were too good to just be graded, so I decided to share them with the rest of the world. I organized a student film festival to showcase their work, and the students were so excited!

One story particularly touched me: a student’s mother and her aunt had not spoken for twenty years. My student had to contact her aunt for the project, but her mom said no. My student said, “So you want me to fail my class?” The mom eventually relented, and the aunt was so happy to participate. At the end of the project, not only did my student get an A and a spot in the festival, but she healed her family. After twenty years, they now have family gatherings again.

This project certainly made research tangible, and it showed my students that digital archives like Gale Primary Sources are a key to the past, but they’re also a road to their futures. Especially for African Americans (like me) or any minority that does not have a strong connection to their history, you can’t know who you really are without knowing your past.

Unfortunately, because enslaved people were denied the right to carry their cultural identity, most of it was lost over time. The traditions that are normally passed down from generation to generation about a person’s family, heritage, and ethnic identity, which leave clues about their ancestors, was stolen from us. Restoring this history, through the use of digital primary source archives that are traditionally hard to access, is key to allowing African Americans to feel whole. The slave trade has left an enormous gap in the history of a people who desire to know the extent of their existence beyond the slave trade. Making these historical connections allows a person to more completely understand the story of their ancestors and their family history. When you know who you are, it will empower you.

Meet the Author

Dr. Bequita Pegram is a history lecturer at Prairie View A&M University, where she teaches U.S. History I and II, as well as Introduction to Digital Storytelling. She also produces her podcast “D.O.P.E. Conversations.” To find out if you have Gale Digital Scholar Lab or Slavery and Anti-Slavery at your institution, visit gale.com/access.