During Black History Month, we celebrate African Americans who made impactful contributions to American history. One of the most important developments of the twentieth century was the civil rights movement. Many Americans, both black and white, fought for equality in access to voting, education, housing, and public spaces for African Americans. Most of the best-known civil rights leaders of this period were male, such as Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Malcolm X, Medgar Evers, and John Lewis. However, many women also made significant contributions, including Fannie Lou Hamer, Pauli Murray, and Dorothy Height. Because of their efforts, black Americans, especially in the South, gained new legal rights and freedoms.

Women and the Civil Rights Movement

Much of the civil rights movement involved challenging accepted societal and legal norms through public demonstrations, lawsuits, and putting lives at risks in areas where change was not wanted or welcomed by whites. In many major public events of the movement, women were often relegated to the background. For example, thousands of women took part in the March on Washington on August 28, 1963. Even though female civil rights leaders played an important role in organizing the march, they were not allowed to march with King and they were not asked to give any speeches that day. Instead, women organizers were told to march on a side street with the wives of the male leaders.

Despite such public snubs, a number of female leaders had prominent, central roles in planning, coordinating, and executing many key events in the civil rights movement. Women put together the nonviolent sit-ins at segregated lunch counters. They also strategized the voter registration efforts during the Freedom Summer, 1964. When the Little Rock Nine forced Central High School to become integrated, a woman, Daisy Bates, was a primary organizer of the whole operation from recruiting the teens involved to ensuring that they were supported during the violence that came with forced integration. Though what these women did for the civil rights movement was not always visible to the public, their work and sacrifice ensured that profound changes took place for blacks in American society.

Fannie Lou Hamer

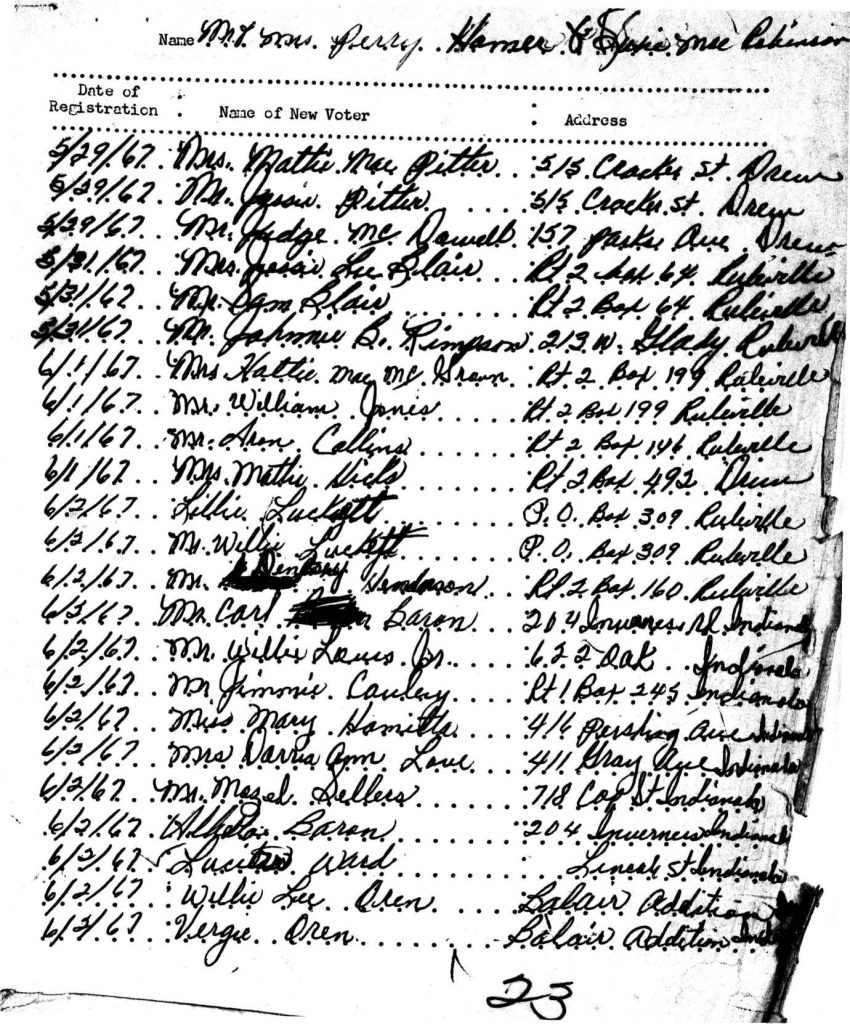

One of the primary focuses of the civil rights movement in this period was increasing the access to the right to vote. Because of personal intimidation and restrictive voter registration laws, only seven percent of African Americans in Mississippi were registered to vote in 1964. Rates in other southern states were at least fifty percent, showing the effectiveness of Mississippi’s efforts to keep black Americans from exercising the right to vote. As her papers show, Fannie Lou Hamer played a prominent role in organizing the Freedom Summer voting campaign in Mississippi.

Born into a family of sharecroppers in Mississippi, Hamer worked in the cotton fields from childhood though she did attend school for several years. She experienced profound acts of racial and sexual discrimination in her home state. For example, she was given a hysterectomy without her consent when she was hospitalized for an unrelated minor surgery in 1961. This procedure was called a “Mississippi appendectomy” because it was so common among black women who entered certain hospitals. Hamer’s forced sterilization contributed to her joining the civil rights movement. She later suffered job loss and other reprisals for trying to register to vote, which also motivated her to seek change.

Because of such acts of intimidation, Hamer became a voting rights activist and desegregationist. As she explained in an interview recorded in the Ralph J. Bunch Oral Histories Collection, “As far as civil rights, a lot people know some—have a long background in civil rights. I didn’t have anything back there. I knew it was something wrong [in Mississippi] but I didn’t know what to do and all I could do is rebel in the only way I could rebel.”

A co-founder of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, the eloquent, passionate Hamer was arrested and beaten in the summer of 1963 for her activism. As the co-founder and vice chair of the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party (MFDP), she gave a speech on national television during the 1964 Democratic National Convention that challenged the anti-civil rights stance of many white Mississippi delegates. She also ran for Congress as the MFDP candidate.

Though many tried to silence her, Hamer’s powerful speeches made her an in-demand speaker, especially for fundraisers for civil rights groups in the 1960s and 1970s. Additionally, Hamer helped found or supported such organizations as the Delta Opportunities Corporation. As these papers demonstrate, this organization worked to improve the lives of African Americans in Mississippi in practical ways. This collection of newspaper clippings shows the depth and breadth of Hamer’s civil rights work and influence.

Pauli Murray

Activist Pauli Murray fought for both civil and women’s rights as a legal scholar, and was the co-founder of the National Organization for Women in 1966. From the start, she was trailblazer as she explained in an extensive interview recorded for the Ralph J. Bunche Oral Histories Collection on the Civil Rights Movement. For example, in 1940, she was arrested for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Virginia as a protest against a law that made segregation legal on public transportation.

Activist Pauli Murray fought for both civil and women’s rights as a legal scholar, and was the co-founder of the National Organization for Women in 1966. From the start, she was trailblazer as she explained in an extensive interview recorded for the Ralph J. Bunche Oral Histories Collection on the Civil Rights Movement. For example, in 1940, she was arrested for refusing to move to the back of the bus in Virginia as a protest against a law that made segregation legal on public transportation.

Her approach to fighting for the civil rights of African Americans focused on the law. In 1950, Murray suggested the legal approach to challenging segregation should not bother with gradual integration but instead center on arguing that segregation was a violation of the Constitution. Many in the civil rights movement, including Thurgood Marshall when he served as lead attorney for the NAACP in the groundbreaking case Brown v. Board of Education, adopted her approach. She described her approach in her her book, States’ Laws on Race and Color.

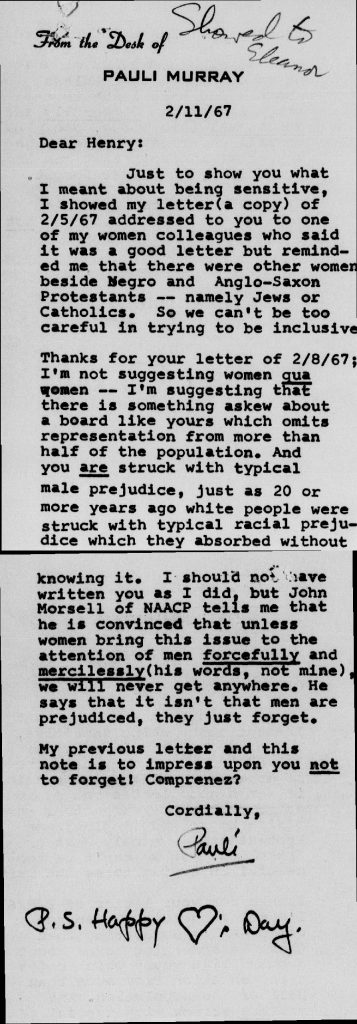

Though Murray’s contributions to the civil rights movement were vital to many of its successes, she was also aware of the sexism within the movement. In 1963, she was among the first to criticize the chauvinism of the civil rights leaders. Her contributions to the movement became marginalized. Though Murray was well known among scholars and academics, the mainstream civil rights movement essentially ignored her because she was open about her lesbianism and feminism. She did not fit in the neat image that the civil rights movement wanted to project about respectability.

Murray did not hesitate to challenge this perspective. In the American Civil Liberties Union Papers, 1912-1990 collection, a letter from Murray to Henry Schwarzschild of the Lawyers Constitution Defense Committee states her position clearly. She opined, “We are presently undergoing a social and political revolution in which all classes formerly deprived are seeking equality. The civil rights movement touched off increasing demands by women, Spanish-speaking Americans, the aged and other groups for participation as persons in decision-making in the United States.”

Murray continued to fight for the rights of African Americans and women throughout her life. In 1983, she wrote in the publication New Directions for Women, “As one who had to cope simultaneously with the twin evils of racial and sexual bias and who had been a civil rights activist in my student days, I saw the women’s movement as essential to the liberation of women of color. My perspective was then, as it is now, the indivisibility of all human rights and the need to develop strong bonds of cooperation between Black and white women.”

Dorothy Height

An advocate for both civil rights and women’s rights, Dorothy Height was not only an activist but also a social worker and educator. Considered one of the so-called “Big Six” of the civil rights movement, she worked for decades on related issues in the United States and abroad. For example, in 1946, Height coordinated integration efforts at the YMCA. The president of the National Council of Negro Women from 1957 to 1997, she was the co-founder of the Center for Racial Justice in 1965. Much of her efforts focused on getting women involved with the civil rights movement and have their concerns become part of the movement.

One method to improve race relations in the South that was favored by Height involved increasing the understanding between white and black women. In Mississippi during the 1960s, Height put together a weekly event where women of both races could come together to talk and find common ground. She undertook such efforts abroad as well. In 1960, Height toured and conducted field work in West Africa. There, as she observed and supported efforts to empower women in various countries, and saw parallels to women in the United States.

Describing her perspective on women in the civil rights movement, Height said in an interview conducted for the Ralph J. Bunche Oral Histories Collection on the Civil Rights Movement, “we are trying very hard to make clear that women are persons and need to participate as equal partners with men, even in the civil rights movement.” She added later in the interview, “we are trying to get the empowerment of black people and we’re hoping that it means that women in proportion as they have the talent and contribution to make.”Air Jordan 1 Retro High OG ‘Rust Pink’ 861428-101 For Sale