| By J. Robert Parks |

Harriet Tubman was a larger-than-life figure even in her lifetime. A few years after the U.S. Civil War, Frederick Douglass wrote her a letter, stating, “I know of no one who has willingly encountered more perils and hardships to serve our enslaved people than you have.” Tubman’s work to free herself and then countless others began 175 years ago this week on September 17, 1849, when she escaped from her enslaver in Maryland. Teachers and librarians who want to help students understand both what Tubman accomplished and why she is so important will find numerous resources in Gale In Context: U.S. History.

Harriet Tubman was born into slavery around 1820 in Maryland. Two of her older sisters were sold to enslavers farther south, and Harriet herself was hired out to a couple when she was barely six years old. Even as a child, she was the victim of beatings and whippings that left permanent scars on her back. When she was in her early teens, she helped a fellow enslaved person to escape by blocking the path of his pursuer, and the white man threw a heavy object that hit Tubman in the head, causing her pain and difficulties for the rest of her life.

In 1849, Tubman learned that her enslaver was planning to sell her and some of her brothers. She had wanted to escape for years, but the possibility of being separated from her family and sold into an even worse situation galvanized her. She would later say, “I had reasoned this out in my mind, there was one of two things I had a right to, liberty or death; if I could not have one, I would have the other.” Neither her husband nor her brothers had the courage to join her, so she set out on her own and then met up with “conductors” for the Underground Railroad to reach the safety of Philadelphia.

A year later, Tubman helped her sister Mary Ann and her family escape from slavery, and soon Tubman was venturing back into Maryland to help other enslaved people escape. Tubman was so effective that she earned the nickname of Moses, after the Biblical figure who led enslaved people to the Promised Land. Tubman’s bravery was especially impressive because it was in 1850 that the Fugitive Slave Act was passed. Not only was she in danger when she was traveling back into the slave state of Maryland, but she was also in danger in the free state of Pennsylvania. Large rewards were offered for her capture, but Tubman continued to journey south to free as many enslaved people as she could. She started taking formerly enslaved people all the way to Canada to keep them safe, but then she returned to Maryland to conduct the next “train” north.

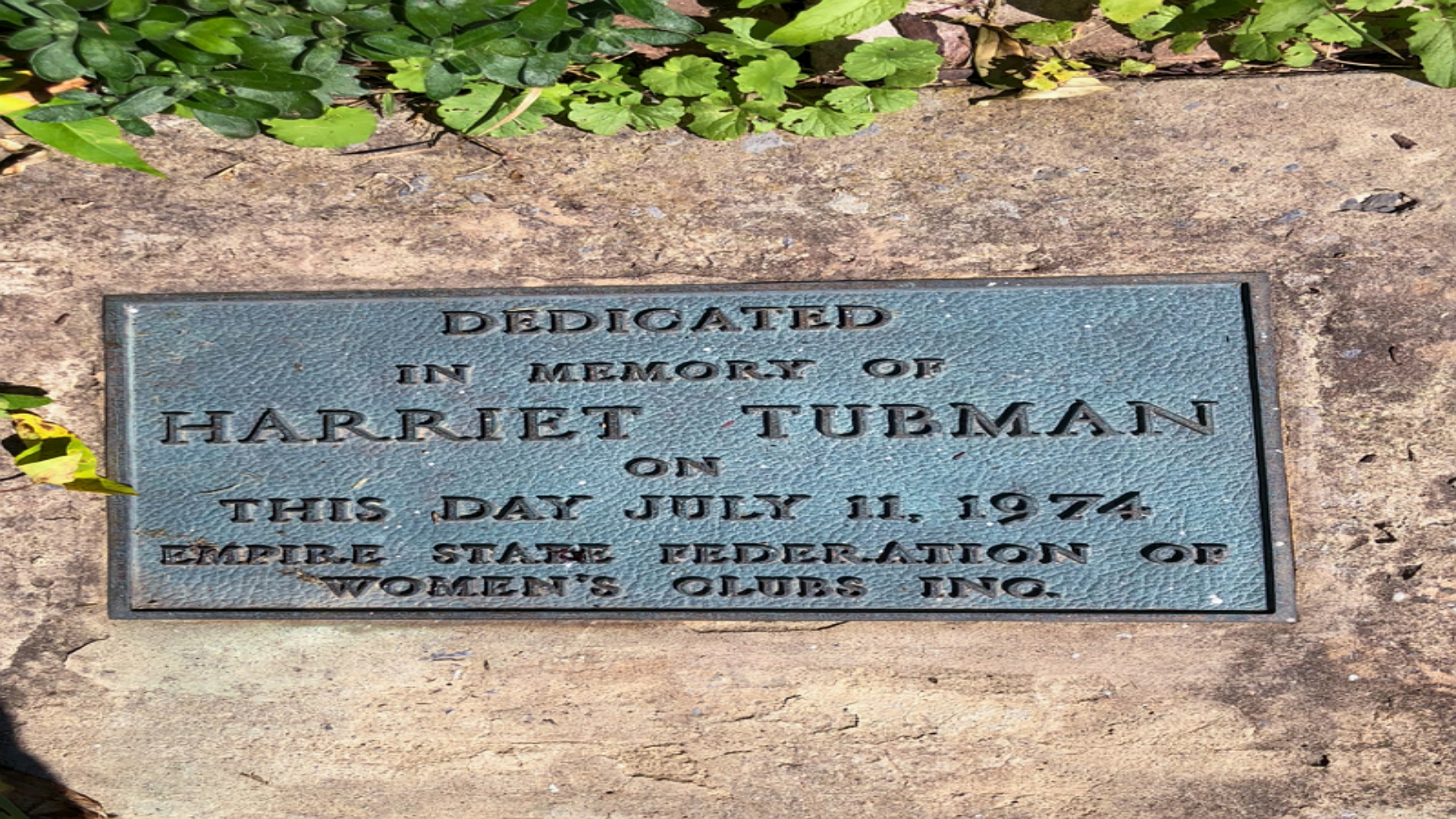

Tubman’s contributions to the abolitionist cause went beyond simply freeing enslaved people. She provided information to John Brown, as he planned his uprising in the late 1850s. Then in the Civil War, she served as a nurse and then a scout and spy for the Union Army. She was particularly instrumental in helping execute the Combahee River raid on June 2, 1863. The raid not only burned numerous Southern plantations to the ground, it also freed nearly 800 enslaved people. Tubman’s exploits later inspired the name of one of the early significant Black feminist groups, the Combahee River Collective. Tubman herself worked for both civil and women’s rights for much of the rest of her life. She helped form the National Association of Colored Women and worked in other women’s rights organizations. She also provided support to formerly enslaved people who had settled in Auburn, New York. Tubman died on March 10, 1913. A bronze plaque was placed in her honor with the following quotation: “On my Underground Railroad I never ran my train off the track and I never lost a passenger.” In 2016, it was announced that Tubman would replace Andrew Jackson as the face on the front of the $20 bill. That transition is expected to happen in 2030.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale In Context: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.