|By Gale Staff|

The 2023 wildfire season scorched over 45 million acres across Canada, an area the size of Washington state. The consequences, however, weren’t confined to the burn zone.

Air monitors in New York City captured some of the highest particulate levels on record, while satellites tracked the same smoke plume crossing the Atlantic and reaching Europe.

Events like the Canadian wildfires are one example of trans-boundary pollution—the movement of contaminants across borders. Smoke can cross continents, altering air quality and affecting public health far from where it began. Incidents like this challenge the notion that environmental policy can ever be purely local. Instead, they show how one nation’s ecological practices can have measurable consequences far beyond its borders.

Gale In Context: Global Issues organizes years of reporting, data, and primary documents in one place, helping high school educators inspire inquiry and spark discussion—including on December 2, World Pollution Prevention Day. The platform’s content collection comes from academic and journalistic sources, providing a trustworthy framework for evidence-based learning.

With this tool in your classroom, your students can dig into the big questions a global citizen asks: how nations coordinate environmental goals, what cooperation looks like when resources or priorities differ, and why prevention depends on shared accountability across borders.

Marine Pollution

Approximately 80% of marine pollution begins on land, where it’s carried seaward by rivers after rainfall, or blown from open dumpsites into coastal waters. Once washed out to sea, sunlight and waves wear larger items into smaller fragments that absorb toxic chemicals and drift through marine currents for decades.

Over time, these currents concentrate marine waste into massive gyres, large rotating ocean systems that gather debris through circular currents. One of the most well-known is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch, an area covering around 620,000 square miles and comprised mainly of plastics that continuously circulate rather than break down.

Samples taken from Mariana trench-dwelling creatures and polar ice show how widely particles spread—evidence that local waste is a global concern.

Near coastlines, coral reefs and seagrass beds are among the first habitats affected by marine debris. Floating plastic blocks sunlight that reefs need for photosynthesis, while plankton and other filter feeders ingest small fragments that carry toxic compounds. Because these creatures are at the bottom of the food chain, these pollutants accumulate in fish caught for human consumption, which coastal communities depend on for sustenance and income.

The impact of plastics as they travel across ocean currents has pushed countries to treat marine pollution as a shared responsibility. In 2022, 175 countries under the United Nations Environment Assembly agreed to negotiate a Global Plastic Treaty—the first international, legally binding agreement designed to curb plastic waste from production through disposal.

Kenya’s Plastic Bag Ban

In Kenya, plastic waste poses both environmental and public-health risks. Along the coast, discarded containers collect rainwater and create breeding grounds for Aedes mosquitoes—vectors for dengue and malaria. Inland, much of that same litter is carried through rivers toward the Indian Ocean, where plastic fragments accumulate in coral reefs and fisheries that sustain local economies.

Kenya introduced a single-use plastic bag ban in 2017, pairing it with unusually strict penalties that included fines up to $38,000 and possible prison terms. A year later, a national survey reported that about two-thirds of Kenyans felt their neighborhoods were noticeably cleaner.

Though challenges persist, such as inconsistent enforcement in rural areas, the combined efforts of Kenya and other East African nations have significantly reduced the flow of lightweight plastics into shared waterways and coastal ecosystems.

Fresh Water Pollution

Less than 3% of Earth’s water is fresh, yet humans depend on it for everything from irrigation and drinking water to power generation and sanitation. Most of these freshwater reserves are constantly moving through the water cycle: excess rainfall becomes runoff that flows into rivers, seeps into groundwater, and eventually returns to larger bodies of water such as lakes, seas, or the ocean—or it evaporates back into the atmosphere.

That constant movement is what makes fresh water a renewable resource, but it’s also what makes our reserves so vulnerable to pollution.

In regional basins, each tributary carries its own mix of contaminants, potentially including things like agricultural runoff, municipal wastewater, and industrial discharge. Because these rivers share connected watersheds, pollutants accumulate as they converge. Along the way, excess nutrients and chemicals change the chemistry of lakes and estuaries.

When rivers reach the coast, they carry those pollutants downstream, creating dead zones where few organisms can survive and introducing inland pollutants into marine food webs.

One example is fertilizer runoff from farms washing into rivers after rain, carrying excessive amounts of nitrogen and phosphorus into nearby rivers. Those same nutrients that help crops grow on land fuel algal blooms in river and ocean water, where thick mats of growth block sunlight and deplete oxygen.

Restoring the World’s Rivers

Many small-scale miners living in the Amazon River basin still use liquid mercury to separate gold from river sediment. Though inexpensive, this compound reacts with organic matter to form toxic methylmercury. It accumulates in fish populations, posing serious health concerns for the Indigenous communities that depend on the river for food.

In recent years, the countries that share the Amazon have begun working together to contain the damage. Through the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization, scientists and residents now monitor mercury levels in fish and soil, while groups like Pure Earth help mining operations switch to mercury-free methods and restore stripped riverbanks with new vegetation.

Another one of the world’s most important rivers, the Ganges, is also showing signs of recovery thanks to direct intervention by India’s Namami Gange initiative. The program targets two primary pollution sources—industrial discharge and untreated sewage—that once left vast stretches of the river unfit for bathing or fishing.

Over the past decade, more than 150 wastewater treatment plants have been built or upgraded in cities along the basin, and factories in heavily industrialized corridors such as Kanpur are now subject to mandatory wastewater monitoring, including fines for violations.

Air Pollution

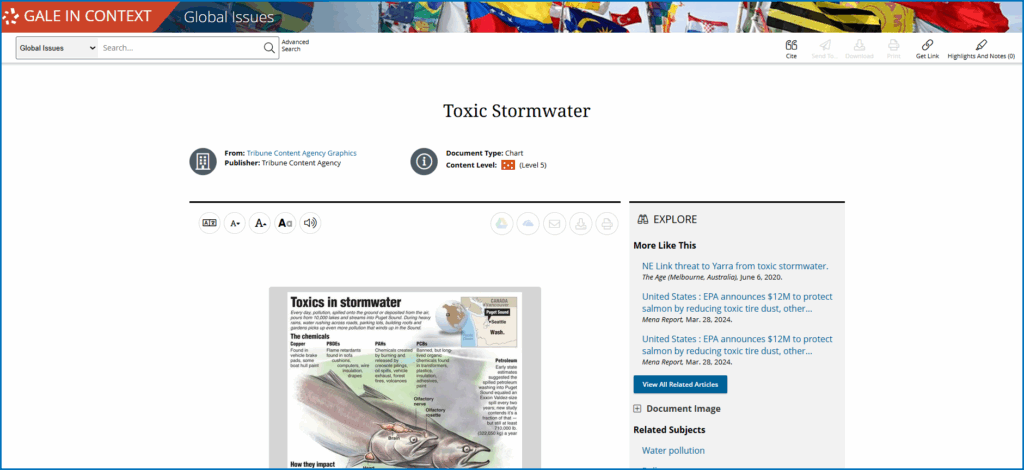

When fuel burns—whether in engines, power plants, or seasonal fires—it releases gases and microscopic solids into the air. Some of these particles, classified as PM2.5, are small enough to remain aloft for thousands of miles, crossing oceans and continents before settling back to the ground. Others react in the atmosphere, transformed by sunlight into ozone and acidic aerosols, which can erode infrastructure, irritate the lungs, and leach nutrients from healthy soil.

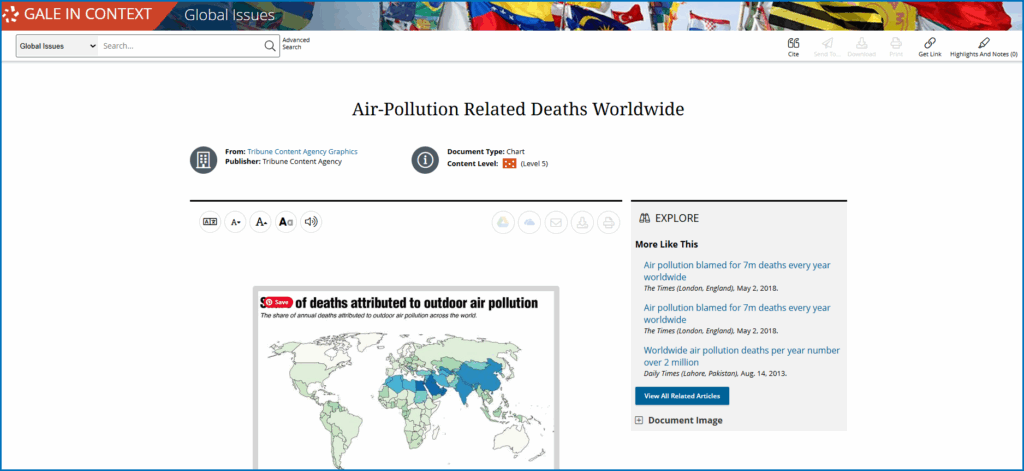

The problem of outdoor air pollution is so pervasive that the World Health Organization attributes approximately 4.2 million premature deaths each year to its effects.

Once pollutants mix into the atmosphere, they’re almost impossible to contain, which makes controlling emissions at the source the most practical way to prevent large-scale air-quality decline.

One solution has been coordinated monitoring between nations to manage trans-boundary air pollution. Both the European Union’s Ambient Air Quality Directive and the Association of Southeast Asian Nations Agreement on Transboundary Haze Pollution require members to track emissions and share data across borders to reduce regional pollution.

China’s Energy Transition

Few countries illustrate both the problem and the potential for change as clearly as China. When a prolonged smog crisis gripped Beijing in the early 2010s, visibility dropped so sharply that airports closed and schools suspended outdoor activities for weeks at a time. The public outcry that followed led to the 2013 Air Pollution Action Plan.

To meet new air-quality standards, China began overhauling major pollution sources. Coal-fired plants added scrubbers that trap sulfur dioxide before it escapes into the air, and city transit networks expanded electric public transportation options to cut traffic emissions.

Since 2013, Beijing’s PM2.5 levels have decreased almost 70% from an all-time high of 101.556 mcg/m³ to 31.74 mcg/m³ in 2022.

Industrial Accidents

Perhaps the most infamous industrial accident of the 20th century was the Chernobyl disaster of 1986.

In April 1986, a reactor malfunction at the Chernobyl Nuclear Power Plant released radioactive plumes that swept out from Ukraine into Belarus and Russia. Within two days, buses evacuated the nearby city of Pripyat, home to roughly 46,000 residents. The surrounding exclusion zone has been quarantined for the past four decades, remaining largely uninhabited to this day.

The Chernobyl event exemplifies how industrial failure, even when isolated, can reach far beyond the boundaries of a single site or nation. Scientists are still studying the long-term consequences of the disaster, including elevated rates of thyroid cancer among people exposed as children and genetic mutations in stray dogs and local wildlife.

Industrial accidents like Chernobyl occur suddenly, releasing immense quantities of concentrated pollutants that ecosystems have no capacity to absorb. Here are a few other significant industrial accidents whose lasting impacts scientists and communities are still working to understand:

- In 1984, a malfunction at a Union Carbide pesticide facility in Bhopal, India, released methyl isocyanate into surrounding neighborhoods, exposing hundreds of thousands of people and leaving groundwater contaminated to this day.

- The Exxon Valdez oil spill in 1989 discharged 11 million gallons of oil into Alaska’s Prince William Sound. Decades later, residue remains in beach sediments and shellfish beds.

- In 2011, a magnitude 9.0 earthquake off Japan’s northeast coast triggered a tsunami that flooded the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. The surge disabled its cooling systems, causing core meltdowns in three reactors. Full decommissioning of the site, including the removal of reactor fuel and contaminated water, is expected to take until 2051.

Preventing Future Disasters on American Railroads

In February 2023, a Norfolk Southern freight train went off the tracks near East Palestine, Ohio. It was carrying several tank cars of vinyl chloride and other industrial chemicals that, upon rupture, ignited. The fire produced a thick cloud containing hydrogen chloride and traces of phosgene that drifted over nearby neighborhoods.

The derailment has forced a reckoning over how hazardous materials move through communities.

After investigators identified an overheated wheel bearing—the so-called first domino that led to the East Palestine derailment—rail companies pledged to adopt new preventive technologies to detect similar failures before they happen. One proposed solution is additional trackside sensors that measure wheel temperatures in real time, alerting crews when a bearing begins to overheat so the train can stop before it fails.

Federal regulators have also begun rethinking how hazardous materials transportation is conducted, with the Department of Transportation drafting rules for sturdier tank cars built from thicker steel and designed to resist punctures or heat damage.

Global Perspectives on Pollution Prevention with Gale

High school students are set to inherit environmental problems generations in the making. Classrooms with resources available through Gale In Context: Global Issues can prepare them to apply what they learn to real environmental challenges and contribute to meaningful solutions.

Contact your Gale sales representative to discover how Gale In Context: Global Issues can equip your students with the evidence and context they need to engage thoughtfully with global challenges.