| By Faith Forrest, Gale Academic Intern |

Biography

Mary MacLane may not be a household name today, but her influence on early twentieth-century literature and feminist thought is undeniable. Much like other nineteenth- and twentieth-century writers who contributed to queer or feminist theories of thought, her impact on contemporary society has only recently been unburied. MacLane’s 1902 autobiographical novel, I Await the Devil’s Coming, offered a striking contrast to the stereotypically stifling environment of her contemporary American West. MacLane’s work not only captivated her contemporary literary scene and early psychoanalytical studies but also left a lasting legacy in queer and feminist literature.

(accessed October 22, 2024).

MacLane was born in 1881 in Winnipeg, Canada. Ten years later, MacLane and her family moved to Great Falls, Montana, and later settled in Butte, a Western landscape that would prove to be sensational source material for her books. MacLane debuted in the publishing industry in 1902 with her first book, originally titled I Await the Devil’s Coming. Due to concerns on behalf of the publishing house, early twentieth-century readers knew her book as The Story of Mary MacLane. In her later life, she published two other books and wrote as a columnist for various newspapers, such as the Denver Post and the Butte Evening News. MacLane’s writing typically takes the form of a diary, but she departs from the mode’s typical function in that she writes for publication rather than the sole aim of expression. Because of this departure, she is often labeled a confessional autobiographist.

The Legacy of I Await the Devil’s Coming

MacLane’s longing for understanding through her penned representation of her inner self is represented largely through an obsession with, and an unabashed yearning for, the Devil. MacLane writes the Devil as a savior, a lover, and a representation of her desire for a more worldly experience. Interestingly enough, MacLane is not the only woman writer of the early twentieth century who lived in the American West who uses a religious figure as a means of obsession and possible escape from a lonely and stultifying environment. It is hard to say if MacLane’s inspiration upon publishing her thoughts resonated largely among her contemporaries or if there is a religious literary trend that begs to be studied that these writers contributed to. Regardless, the existence of such a thread ought to be discussed to understand this period of literature.

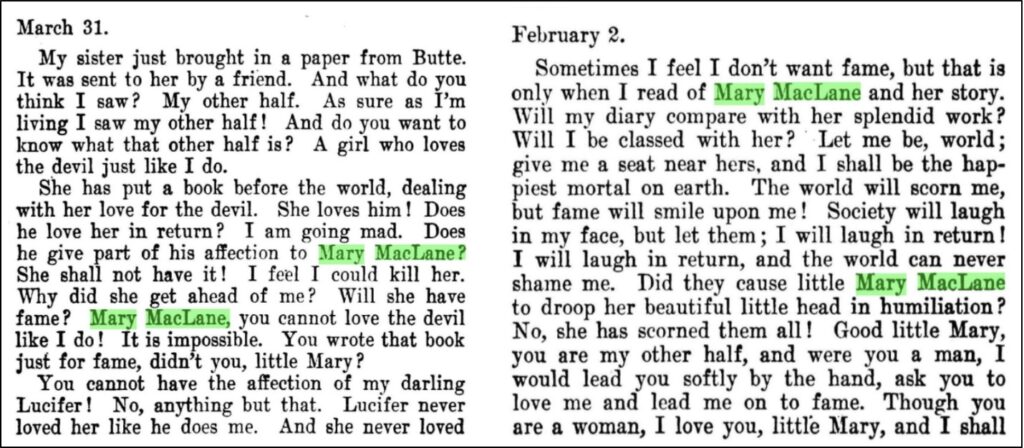

Published in 1911, The Diary of a Utah Girl by Mrs. W. J. McLaughlin bears a striking resemblance to MacLane’s debut work. From McLaughlin’s initial illustration depicting a woman kissed by the Devil to the protagonist’s longing for Brigham Young in the first diary entry, MacLane is both a fountain of literary inspiration and a cemented character in the narrative. Although McLaughlin’s book was released nine years after I Await the Devil’s Coming, she first mentions MacLane in a diary entry dated March 31, 1902, referring to her as her “other half.” MacLane serves as a subject of competition to McLaughlin—“I think my diary will make Mary MacLane go back and sit down, for she does not express herself like I do” (148)—as a source of jealousy—“Does he (the Devil) give part of his affection to Mary MacLane? She shall not have it!” (34)—and as a relatable counterpart that she adores—“Good little Mary, you are my other half, and were you a man, I would lead you softly by the hand” (84). The threads of queer adoration, religious idolization, and the self-assigned “genius” run deep throughout McLaughlin and MacLane’s work, and testify to the spread of MacLane’s form and thematic contributions.

Exemplifying MacLane—Book Reviews & Social Subjects

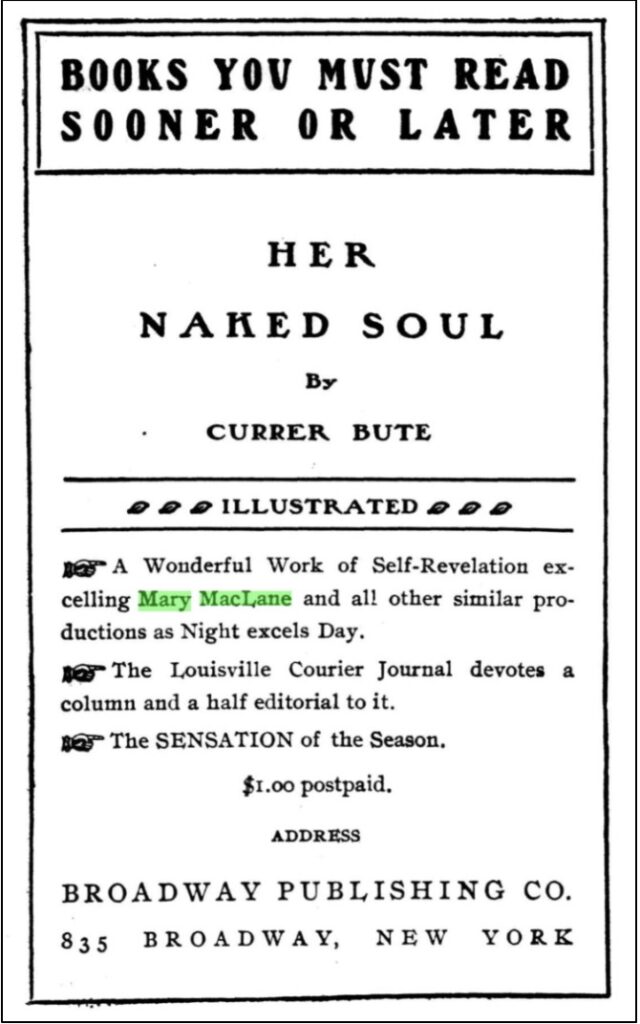

The widespread celebration and criticism of MacLane’s first book cemented her as a standard of exemplariness in unconventional literature. Her reach extends beyond individual inspiration and materializes as a descriptive touchstone in book reviews. The Broadway Publishing Co. included adverts titled “Books You Must Read Sooner or Later” at the end of their published books to advertise other recently released works they had published. One of these showcases Her Naked Soul by Currer Bute, described to be a “wonderful work of self-revelation excelling Mary MacLane,” included at the end of books like The Hospital Cap by Oliver Perry Manlove (1906) and Twentieth Century Goslings: A Modern Love Story (1906) by Frances Mead Seager. MacLane was used as a marketing tactic—authors were measured against her raw and introspective style to promote their own. In doing so, the publisher acknowledges her significant role in shaping a new wave of confessional literature. Such comparisons reveal the public allure of introspective narratives in early twentieth-century literature, and position MacLane as a benchmark for her contemporaries.

(accessed October 22, 2024).

Hall groups Mary MacLane with other autobiographists and poets, such as Marie Bashkirtseff (whom MacLane proclaims as one of her largest inspirations in I Await) and Ada Negri. Hall claims that literary men express internal emotions and feelings through taking direct action externally and that male authors write with “less abandon” during the adolescent stage than literary women. He notes that “a male Bashkirtseff” is more likely to appear than “a male MacLane,” characterizing the latter as a singular novelty while simultaneously gendering the nature of literary introspection. Further, Hall uses MacLane as an example of a subsection of adolescent girls who exhibit directionless but promising futures. These girls who have reached the stage of “first maturity” possess keen insights and senses that reveal the “characterlessness normal” of a stage that “seems to have least unity, aim, or purpose” (629). A specific developmental experience in the field of psychology is here situated by MacLane as both an outlier in literature and a social figure emblematic of such an experience.

(accessed October 22, 2024).

Conclusion

Mary MacLane’s bold writing provides an interesting lens when thinking about early twentieth-century literature and feminist thought. As both a literary and a cultural figure, MacLane remains a critical point of reference in understanding the elements of early feminist thought and the evolving landscape of American literature, challenging readers to reconsider the voices of those who dared defy convention long before it was fashionable to do so.

Meet the Author

Faith is a senior at the University of California, Los Angeles where she double majors in English and political science. In her free time, you can find her managing her school’s farmers market, scrapbooking, or playing pickleball with her friends!