| By J. Robert Parks |

Imagine you’re on a game show where you’re asked progressively more difficult questions about people and events in U.S. history. Admittedly for some of you, that might sound like an opportunity to shine; for others, it’s a potential nightmare. But I’m guessing that many readers could get the first question right in a potential “Give Me Liberty, or Give Me Death!” category. Yes, that was said by Patrick Henry. If the next question was “Who was he speaking about?” again the majority of us could pick out “the British.” But the questions of when Henry said it, where he said it, and the context for why he said it might stump all but the history teachers among us. The answer to the first of those, by the way, is March 23, 1775, which means Henry gave his speech 250 years ago this week. Educators and librarians looking to help students connect with the people, places, events, and ideas that were critical to the Revolutionary War will want to explore the abundance of resources in Gale In Context: U.S. History.

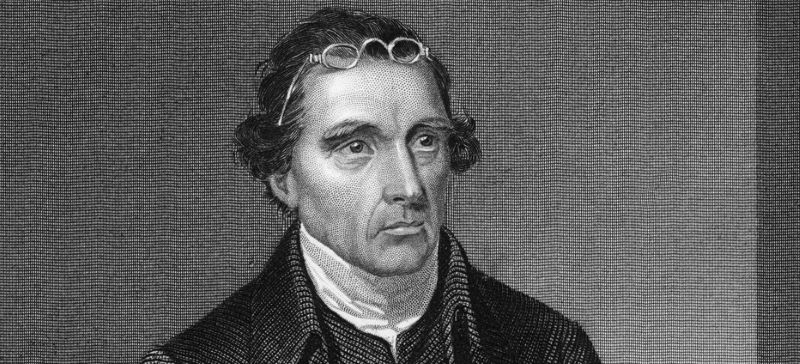

Henry was born on May 29, 1736, in Studley, Virginia, near Richmond, and died on June 6, 1799, in Red Hill, Virginia, across the Chesapeake Bay. He lived his entire life in the colony and then state of Virginia. His family couldn’t afford to send him to college, and his early efforts in starting a store and then running a farm ended in failure. He took up law in 1760, more out of desperation than any expectations of success, but he had a gift for oratory and his timing was fortuitous. Three years later, he came to prominence by attacking the British over what was known as the “Parson’s Cause.” His speech led to his election to Virginia’s House of Burgesses in 1765, and he continued to proclaim his fervent belief in colonial rights and particularly against the hated Stamp Act.

As colonial opposition to British rule grew over the next decade, Henry was at the forefront of that movement. He was elected as a delegate to both the First Continental Congress in 1774 and the Second Continental Congress in 1775, but game show contestants who chose one of those as the site for his famous speech would be deemed incorrect. It was in fact the Second Virginia Convention in March 1775 where he made the speech that earned him a place in U.S. lore.

The context for Henry’s speech was that Lord Dunmore, the British-appointed governor of Virginia, had dissolved the House of Burgesses for its support of the anti-British citizens of Boston. Henry and other members continued to meet, however, and Henry and others argued that the colonists should prepare to break with British rule. Even some of Henry’s allies were against a war with the British, but he argued in his speech that the colonists had done all they could to resolve matters peacefully. Therefore, he argued, war was soon to come and that the colonists should prepare for it and indeed embrace it: “I know not what course others may take, but as for me, give me liberty, or give me death.”

Henry is remembered as a Revolutionary War hero, but ironically, he served only briefly as a soldier. Instead, he was elected the first state governor of Virginia in 1776 and was reelected in 1777 and 1778, and he helped recruit Virginians for the colonial war effort. After the Revolutionary War victory in 1783, he was elected governor of Virginia again in 1784 and served until 1786.

Henry’s post-revolutionary activities aren’t as well-known, maybe because they don’t line up with our traditional beliefs about the Founding Fathers. He publicly opposed the passage of the U.S. Constitution, proclaiming to his fellow Virginians that the Constitution would enable the North to “take your [enslaved people] from you.” He was a particularly vociferous advocate for the Second Amendment because he believed that enslavers should have the right to their own militia in order to stand up against those who would oppose the institution of slavery.

As a lifelong Virginian, Henry’s commitment to matters within his state’s borders seemingly took precedence over national concerns often connected to the Founding Fathers. Perhaps the audience for his famous quote—Virginians instead of delegates from the different colonies—helps contextualize his considerations of liberty over death. His advocacy was for liberty at an even more precise level than the liberty of a nation.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale In Context: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.