| By Gale Staff |

In 1978, a 24-year-old California educator named Molly Murphy McGregor was teaching when a student raised his hand and asked her to explain the Women’s Movement. Molly didn’t have a good answer. Instead, she turned to the classroom textbooks and, to her dismay, discovered next to nothing about women’s history.

At the time, the standard school curriculum did not include stories about Abigail Adams, Mary Wollstonecraft, Sarah Parker Remond, or the bold team behind the first Women’s Rights Convention. Murphy McGregor recognized the gap in the curriculum as a disservice to her students and helped launch the first-ever Women’s History Week in her school district.

The initiative quickly became popular, even catching the attention of then-president Jimmy Carter. Less than a decade later, in 1987, Congress recognized that a week wasn’t enough, and officially designated March as Women’s History Month.

This March, turn to your library’s Gale Primary Sources. To get started, dive into the platform’s dedicated Women’s Studies Archive: Female Forerunners Worldwide to find an impressive collection of primary sources from trailblazing women and women’s organizations, spanning from 1759 to 2002. By exploring these first-hand accounts, college students can develop a better appreciation of the suffrage movement’s goals, tactics, internal dissension, sacrifice, and key moments of triumph.

Meet the Pioneers Behind the First Women’s Rights Convention

The journey toward the 19th Amendment took off in 1848. Activists Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucretia Coffin Mott, Martha Coffin Wright, Mary Ann McClintock, and Jane Hunt organized in Seneca Falls, New York, to hold the first Women’s Rights Convention. During this two-day conference, members of the gathering drafted and ratified the Declaration of Sentiments, inspired by the Declaration of Independence, which outlined some of the movement’s grievances and political ambitions.

Along with the right to vote, the document outlined ten additional resolutions for women’s equality, including the right to hold public office, fair wages, education, and equal same rights in child custody and divorce. All of these passed unanimously—except one: the right to vote.

Convention leaders insisted women’s suffrage was a powerful symbol for the movement and essential to their long-term success. However, dissenters believed the idea was not imperative and, frankly, too radical; they argued that demanding voting rights would detract from their group’s overall demands.

Despite the controversy around the voting resolution, this sentiment would soon become the bedrock of the women’s rights movement. The Seneca Falls convention was a watershed moment for women’s suffrage in the United States and civil rights more broadly.

Consider the Global Impacts

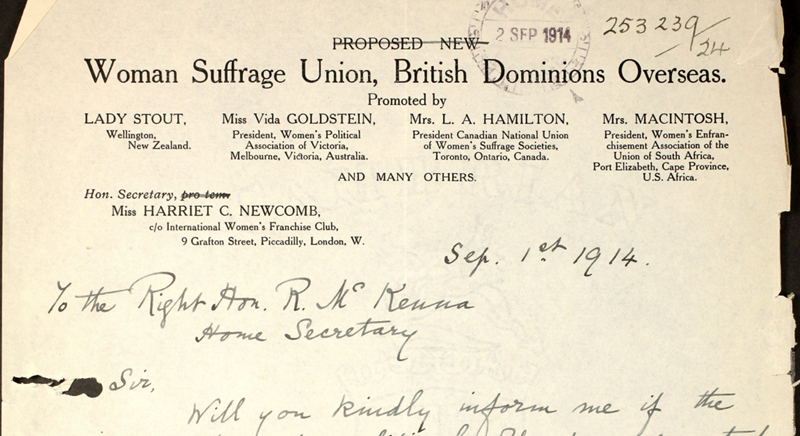

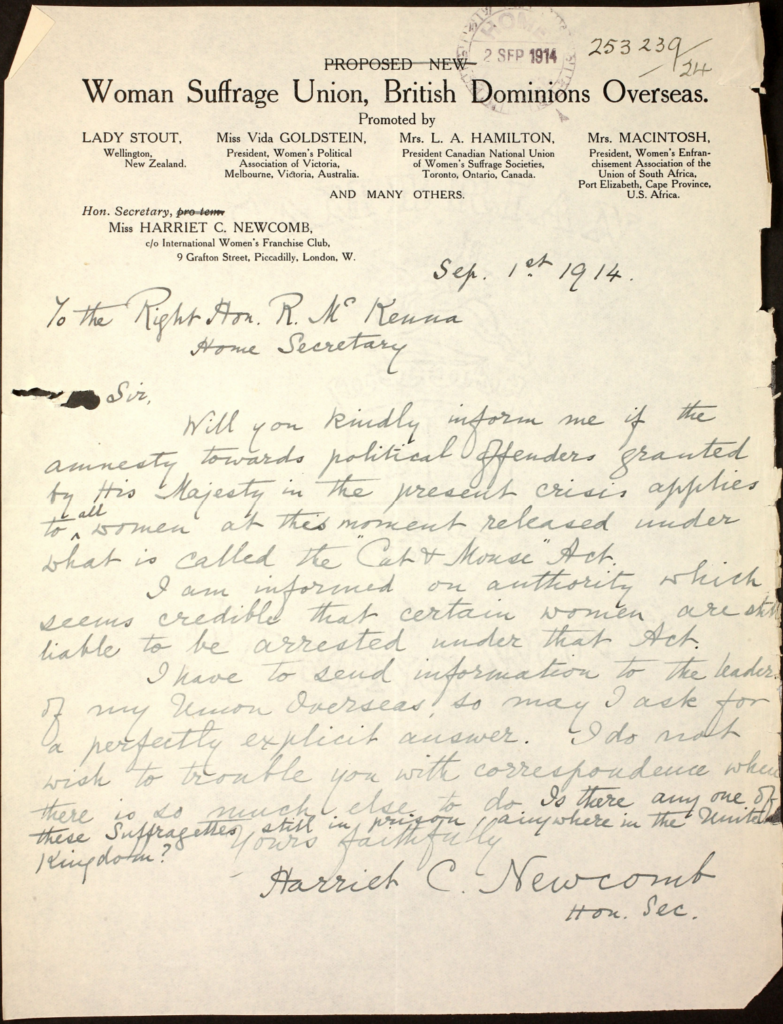

As documented throughout Gale’s Suffragettes 1886–1935 collection, the discussion around women’s right to vote wasn’t limited to the United States—it was a global topic throughout the late 19th and early 20th centuries, and suffragettes worldwide resorted to disruptive tactics. For example, in 1911, the Women’s Freedom League in the United Kingdom boycotted the country’s 1911 census, arguing that without the right to vote, the government shouldn’t count or tax British women.

Borrowing these and other nonviolent strategies established by previous campaigns in the American labor movement, U.S. suffragettes protested at public events, picketed at the White House, and planned peaceful parades and marches. Many participants were arrested, causing some to resort to hunger strikes.

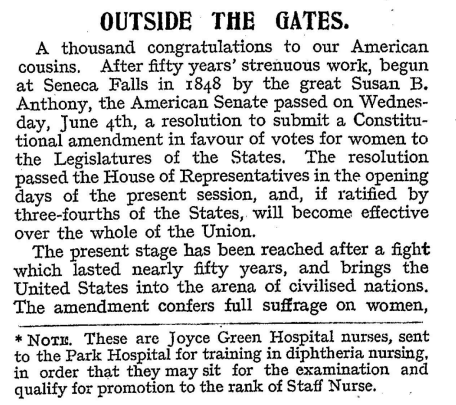

When New Zealand became the first nation to recognize women’s right to vote in 1893, the tide had officially turned. Australia, Finland, and Norway followed suit within a few years, and a total of 20 nations would grant women the right to vote before the United States, including Germany, Poland, and several members of Soviet Russia. It wasn’t until 1920 that Congress voted to add the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, solidifying the global advances made by the women’s movement.

Following the outbreak of World War II, women were instrumental in filling vacancies in the labor market and maintaining the global economy. Despite the war’s end in 1945, many women refused to concede their new financial autonomy and influence in the post-war era. In fact, one 1943 article from the Historical Nursing Journals collection predicted “an immense untapped source of power in the capacity of women,” noting the change that a generation of educated, politically-minded women could bring to the post-war landscape.

Throughout the mid-20th century, women continued to fight for expanded career opportunities, access to birth control, and equal pay. The United Nations proclaimed 1975 as International Women’s Year, and member countries convened in Mexico City to develop an agenda to advance women’s rights globally.

Celebrate the Women of Color Who Pushed for Equal Voting Rights

In 1851, a formerly enslaved person named Sojourner Truth delivered a powerful speech entitled “Ain’t I a Woman?” to the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio. In it, Truth described the grim realities of being a black woman in America and the intersectionality of sexism and racism. Her address was the only one at the convention to boldly demand universal suffrage.

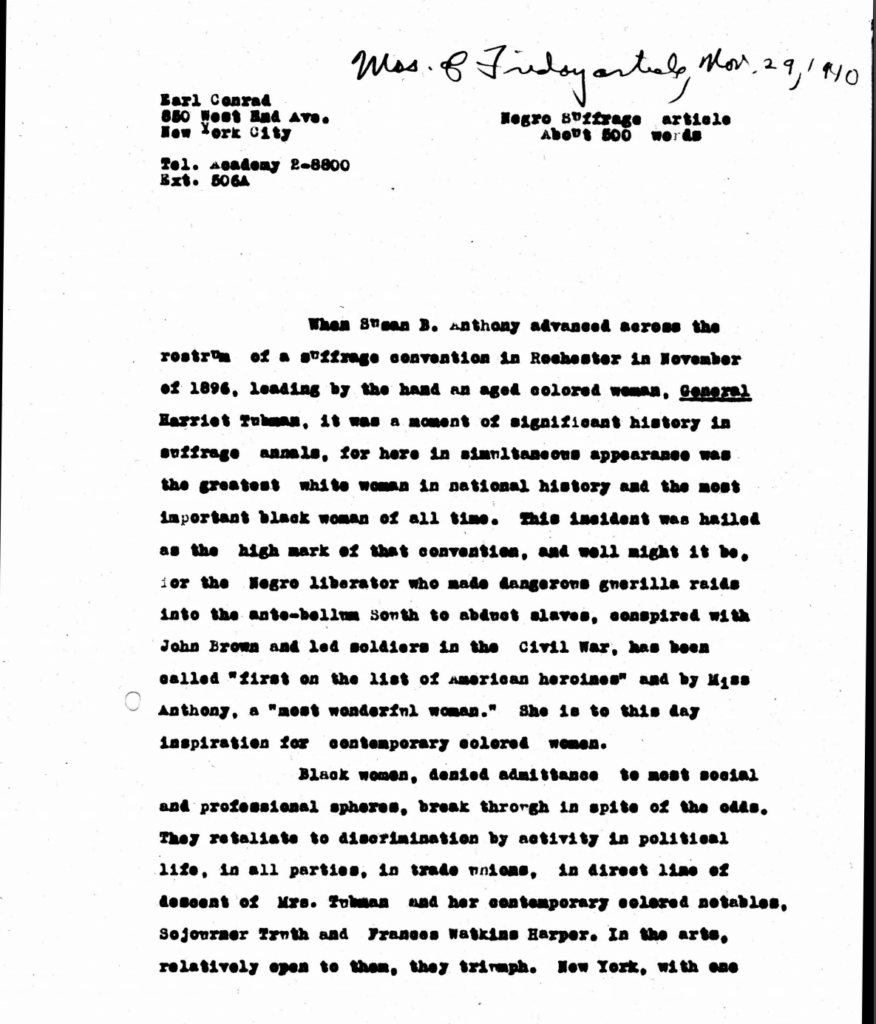

Black women were a vital voice in the women’s suffrage movement. For example, Harriet Tubman, a well-known abolitionist and Underground Railroad conductor, became an outspoken suffragette. Tubman, as featured in Gale’s Earl Conrad/Harriet Tubman Collection, had a well-documented friendship with the famous Susan B. Anthony. The two were seen together in attendance at the 1896 Women’s Rights Convention in Rochester, New York, creating a powerful image for universal suffrage.

At times, however, there were tensions within the movement. After the Civil War, some suffragettes campaigned against the 15th Amendment, which granted voting rights to formerly enslaved men to the exclusion of women. Some demanded that the legislation should include women as well, arguing that the amendment did not go far enough to address inequality. However, some leaders, Elizabeth Cady Stanton among them, relied on discriminatory rhetoric, suggesting white women should be prioritized for voting rights before black men. This racist language ultimately divided the women’s suffrage movement.

While the 19th Amendment granted voting rights—in theory, at least—women of color still faced immense barriers to voting. Black women were often intimidated, banned from polling locations, and even experienced violence when attempting to exercise their rights. Comprehensive women’s suffrage was not codified until 1965 with the Voting Rights Act, which protected voting rights for people of all backgrounds, regardless of race or gender. More than a century passed between the first Women’s Rights Convention in 1848 and the 1965 Voting Rights Act.

Through the first-hand perspectives in Women’s Studies Archive: Female Forerunners Worldwide, students can analyze the complex history and nuances of our country’s imperfect but persistent progress toward equality.

Gale’s Women’s Studies Archive: Female Forerunners Worldwide can help you elevate women’s accomplishments and perspectives within your academic space. This unrivaled collection is the perfect companion to bring Women’s History Month to your campus.

Ready to learn more? Contact your local sales representative for additional information.