| By Clematis Delany |

A king without a throne, a dashing young prince, and an army of exiles. These basic components of Jacobitism – with some misty lochs, rugged Highlanders, scheming Catholics and royal courts thrown in – lend themselves perfectly to high Romance and adventure. It is no surprise then, that the Stuarts and their Jacobite supporters provided inspiration for early Scottish Romanticism, evident in the works of authors such as Sir Walter Scott and Robert Louis Stevenson, the poetry of Robert Burns, and popular tunes like The Skye Boat Song. With a core narrative of brave young men fighting a doomed cause against an oppressive regime, (particularly embodied in the merciless Duke of Cumberland), the stories surrounding the two Jacobite risings remain popular today, as the recent success of Diana Gabaldon’s Outlander series of historical novels has shown.

Such narratives tend to stop shortly after 1745, as the decline of ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ into a paranoid and violent drunk falls somewhat short of the promise of the rightful heir sailing off to Skye. Likewise, the perennial money troubles and in-fighting of the Jacobite court don’t make it into stories such as Waverley and Kidnapped.

On the other hand, adding a Romantic spin to the saga was a contemporary part of Jacobitism, particularly in Scotland, where the traditional powers and way of life of the clans were threatened, and ultimately broken, by the Hanover monarchs. Toasting ‘the king over the water’, decorating glassware and jewelry with Jacobite symbols such as crowned thistles and white roses, and wearing a white cockade were all elements of Jacobite culture. Rejecting the Hanover monarchy for the house of Stuart also fed into contemporary issues of Scottish religion, nationalism and rebellion against the Union of Scotland and England – the Stuarts were closely associated with Scotland and were careful to maintain this link in exile, as Scotland provided a basis for support in all the schemes of risings and Restoration throughout the eighteenth century.

The forthcoming addition to Gale’s State Papers Online series, The Stuart and Cumberland Papers from the Royal Archives, Windsor, illustrates the origins of Scottish Romanticism in Jacobitism in many ways, but particularly through narratives of the risings of 1715 and 1745, and in the collected poems of Jacobite supporters. Two journals from the rising of 1745 sing the praises of Charles Edward, later known as Bonnie Prince Charlie, and paint him in a very favorable light, emphasizing his popularity with the Scottish people and his own bravery and endurance while on the run after the Battle of Culloden had been lost in 1746.

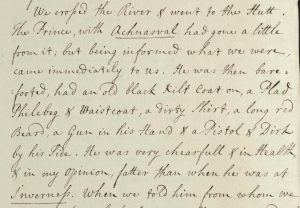

In a narrative of 1746, copied from a manuscript found on a Mrs. Cameron when she was arrested en route to Paris in 1748, Charles appears in a very heroic mold, wearing tartan, sleeping on the bare ground and bravely making his way through Highlands riddled with Hanoverian soldiers.

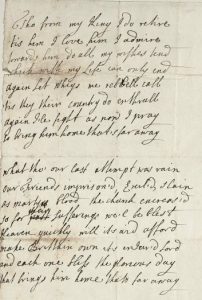

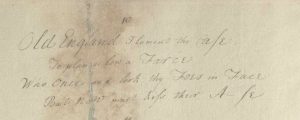

The most obvious glorification of the Stuarts and their cause was always, inevitably, in the art and symbolism that sprung up around it. Though the early Jacobite poems were more notable for their enthusiasm than their literary skill, they show the roots of the later Romantic revival in their heroes, their yearning for a lost land, and the reassertion of the divine right of the Stuarts. James Francis Edward, the Old Pretender, appears as a suffering hero and a paragon of virtue.

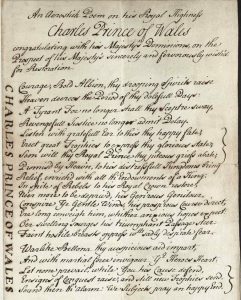

Charles likewise received many tributes, particularly in the years surrounding 1745, such as this solemn acrostic:

Perhaps it was a good thing for Romanticism that the Jacobites never were restored; a young prince fighting for his birthright is an undeniably Romantic image and fertile ground for any writer, and the practical realities of a new monarch could hardly fail to fall short of such idealized notions. Had the Stuarts returned, literature, as well as politics, might have taken a very different road. On the other hand, this would also have meant some of the lyrical flights of the Jacobite poets would most likely have gone unwritten, sparing the world some truly execrable verse…

Please note: All sources mentioned are available in the digital archive State Papers Online: The Stuart and Cumberland Papers from the Royal Archives, Windsor.

Very interesting, and no doubt had the Bonnie Prince been successful, he would most likely have turned his back on the Geals for the delights of London society. But what of Cumberland? What was he really like? I have a vague notion of a fat, egotistical, spoilt great of a man, not to mention a heartless murderer! Or was he really a lovely chap?