For many students, Labor Day is just a bonus Monday off—a final nod to summer as back-to-school routines get underway. But behind the long weekend barbecues, there lies the story of a turning point in American labor history.

Elementary educators don’t need to devote an entire unit to make the holiday meaningful. With the right support, like the resources available through the Labor Day topic page on Gale In Context: Elementary, a single class period can prompt thoughtful conversations about why the holiday exists, how it has evolved, and what it looks like today.

What Work Looked Like in the 19th Century

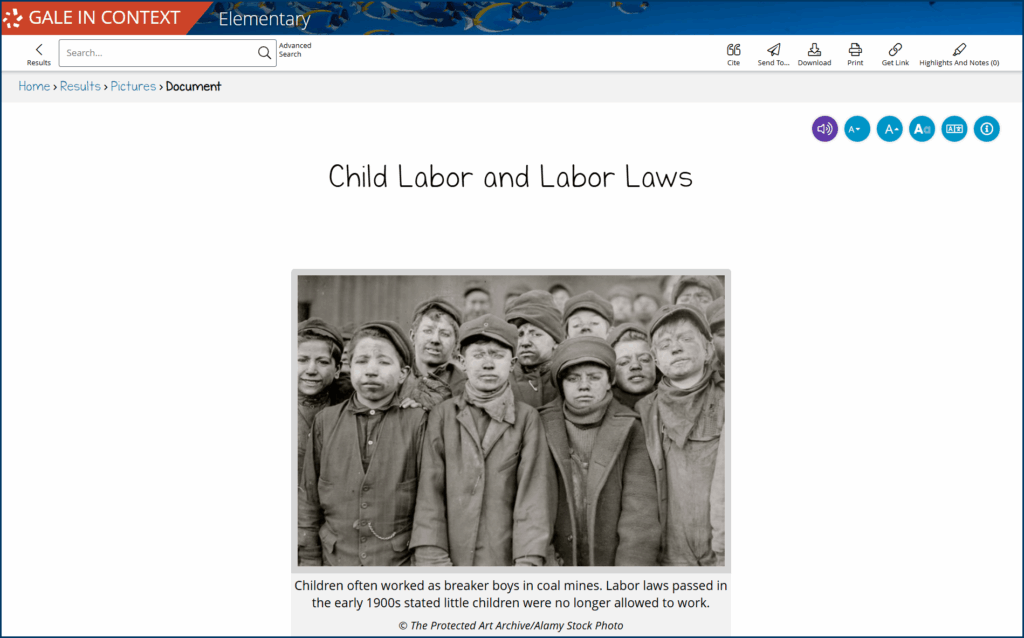

By the late 1800s, the American economy was booming thanks to the Industrial Revolution—but much of that growth came at a steep cost to the people who kept it running. Adults and children alike worked long hours in factories, mines, mills, and rail yards. In many cases, families depended on every member contributing to the household income, even if that meant sending a child to work instead of school.

Factory jobs often required standing on your feet for 12 hours or more, repeating the same motion over and over again on an assembly line. The noise from machines could be deafening, and the air hard to breathe—filled with textile fibers or chemical fumes. Injuries were common, too. Fingers crushed by gears, lungs scarred by dust, backs strained from heavy lifting.

Children faced similar risks. Boys worked underground in coal mines as “breaker boys,” sorting lumps of coal with bare hands and breathing in black dust. Others worked as messengers, delivery runners, or newsboys in city streets, darting between carriages and trolleys.

Girls often worked in canneries or textile mills, where they tended machines that could catch hair or clothing if they weren’t careful. Most children earned a fraction of an adult’s wages, but their income was often vital to the family’s survival.

There were no laws that limited the number of hours someone could work. There were no guaranteed days off—not even on holidays. And if a worker got injured, there were no sick days, no health insurance, and no legal protections. If you couldn’t keep up, you could be fired without warning.

At the time, most Americans saw these conditions as normal. But as cities grew and more workers shared the same struggles, they began to realize that change might be possible if they demanded it together.

Classroom Research Activity: Explore 19th-Century Jobs

Invite students to use Gale In Context: Elementary to investigate what different kinds of work looked like in the 1800s. Each student can choose a job that interests them—such as coal miner, factory worker, or seamstress—and answer the following guiding questions:

- What kind of tasks did this person do every day?

- Who usually held this job (children, men, women)?

- What tools or equipment did they use?

- What made the job difficult or unsafe?

For younger students or emerging writers, encourage them to draw a picture of someone doing the job they researched. You may want to provide sentence frames to help with writing, leaving spaces for the profession, setting, and work-related actions.

To further support students as they build confidence in writing, allow them to work in pairs or small groups while discussing the jobs. Verbalizing ideas before writing can be beneficial for students who are still developing their literacy skills.

For multilingual learners, in particular, speaking supports language development in a way that aligns with the natural order of acquisition—listening, then speaking, then reading, and finally writing. Encouraging students to talk through their ideas helps lower the entry barrier for writing and offers essential practice in the skills that come before it.

The First Labor Day

In response to poor working conditions, labor organizers began calling for reforms.

The first Labor Day strike took place in New York City on September 5, 1882. It was organized by the Central Labor Union, a coalition of trade unions representing skilled workers across the city. The plan was ambitious: a march through Manhattan, followed by a picnic and concert in Wendel’s Elm Park, a popular gathering place for working-class communities.

Attendance was a gamble. Workers weren’t guaranteed time off, and joining the march meant risking a day’s pay or even their jobs. Still, more than 10,000 people showed up. Marchers were grouped by trade—shoemakers, dressmakers, cigar rollers, and stonecutters—and carried handmade banners that called for the eight-hour workday and safer conditions.

Over the next decade, labor celebrations gained momentum, particularly in industrial boomtowns like Chicago, Detroit, New York City, and Pittsburgh. However, it wasn’t until shortly after the 1894 Pullman Strike—a nationwide railroad boycott that turned violent when federal troops intervened—that Congress passed legislation making Labor Day a national holiday.

Why the First Monday in September?

As labor organizations grew in size and influence, leaders like P.J. McGuire of the American Federation of Labor began calling for a day to recognize workers nationwide. In 1882, McGuire proposed setting aside the first Monday in September to honor the contributions of working people and the unions that represented them. The date was chosen because it offered a well-timed break, halfway between Independence Day and Thanksgiving.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think so many workers were willing to risk their jobs to join the first Labor Day parade?

- What message do you think the first Labor Day parade sent to other people watching in the city?

Celebrating Labor Day

In the early 20th century, Labor Day events were closely connected to the labor movement. Trade unions would organize parades, with workers marching under the names of their professions. Spectators lined the streets to cheer on friends and family members, then gathered in city parks for union-sponsored picnics and amateur baseball games. For many working families, it was one of the only guaranteed days off all year.

How We Celebrate Today

While a few cities still hold traditional parades, most modern Labor Day events focus less on organized labor and more on leisure. Many communities host festivals and other public events as an end-of-summer celebration. Although these events don’t necessarily put the holiday’s original purpose front and center, that gap gives educators a chance to encourage discussions about how the nature of work has changed—and why we continue to celebrate the holiday today.

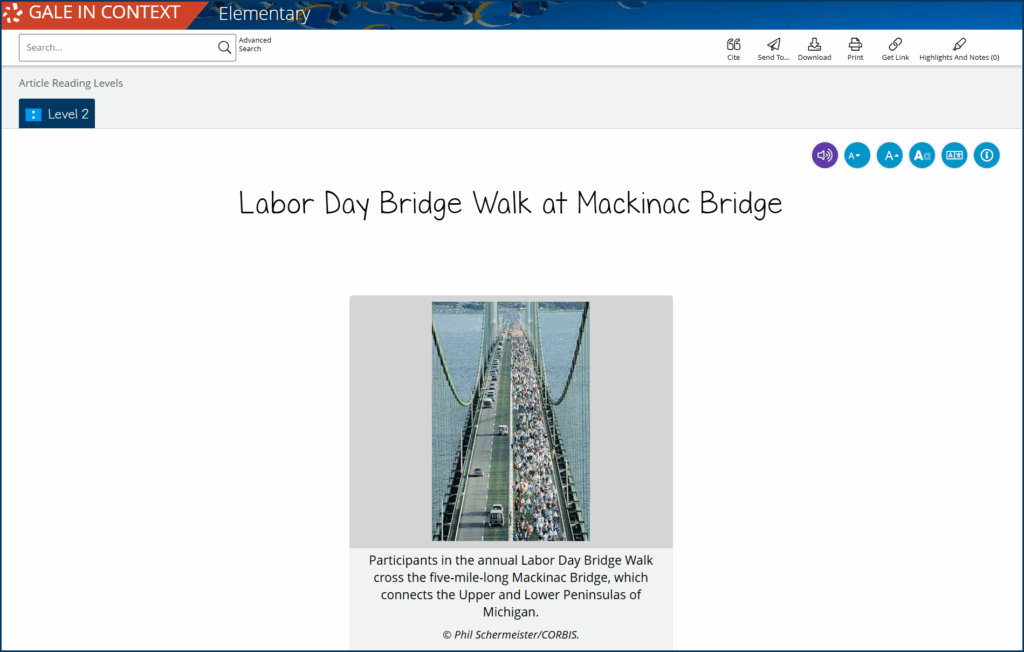

Mackinac Bridge Walk – St. Ignace, Michigan

Every Labor Day since 1958, tens of thousands of people cross the Mackinac Bridge on foot. Michigan’s governor leads the way across the five-mile stretch, suspended up to 200 feet over the convergence between Lakes Huron and Michigan. In smaller towns like Cedar River, “mini bridge walks” offer a scaled-down version of the experience, sometimes involving dogs, wagons, or even ponies.

Black Diamond Labor Days – Black Diamond, Washington

In Black Diamond, a former coal town in western Washington, Labor Day weekend still includes a parade, but it’s the oddball competitions that stand out. There’s a little something for everyone: participants can catch their own frogs and enter them in a race to the finish line, put their taste buds to the test in pie and watermelon eating contests, or unleash their inner prankster in the toilet paper unraveling challenge.

Bread & Roses Festival – Lawrence, Massachusetts

The Bread & Roses Festival commemorates the 1912 textile strike in Lawrence, a multiracial, multilingual uprising led largely by immigrant women. The name comes from a rallying cry of the era: “We want bread, and roses too,” which demanded not only fair wages but also dignity and respect. The festival features live music and dance, labor history tours, historical reenactments, poetry readings, and cuisine from the city’s diverse immigrant communities.

Doggy Dips at Community Pools

In dozens of cities, the end of pool season comes with a loud, furry finale: dogs in the deep end. After Labor Day, many public pools close for the year, and some communities mark the occasion by inviting pets in for one last swim before the water is drained. Some pools charge a small entry fee to support local shelters, while others simply open the gates and let the Labradors loose.

Discussion Questions

- Why do you think Labor Day celebrations have changed over time?

- How does your family usually spend Labor Day weekend?

- If you could create a new Labor Day tradition for your community, what would it be?

In the early days of the school year, you can harness students’ eagerness to learn by introducing elementary learners to the history behind Labor Day—and how to research it using Gale In Context: Elementary.

While they’re exploring the origins of the holiday, learners can get hands-on practice navigating the Gale interface and using built-in supports like ReadSpeaker text-to-speech and adjustable reading levels. Starting out with this low-stakes, high-interest lesson helps them build early familiarity with a platform they’ll return to for deeper, more complex research projects throughout the year. Meanwhile, you’ll feel confident knowing they’re working with age-appropriate content in a safe, closed environment.

Reach out to your Gale sales representative to learn more about how the platform can encourage students to follow their curiosity about the world around them.