| By Gale Staff |

When the first separatist Puritans stumbled off the Mayflower gangplank onto the sandbars of Cape Cod on November 11, 1620, they brought with them a profound sense of religious duty and reverence for worship. Still, they weren’t big supporters of celebrations during the holy days. The sentiment was so strong that Easter and Christmas were banned in the New World from 1659 to 1681.

The infamous hysteria-kindling witch hunter Cotton Mather was none too pleased when the law was repealed, stating that these celebrations were so unholy that they fell into the territory of worshipping non-Christian deities. He made that quite clear in a Christmas Day sermon titled “Grace Defended. A CENSURE ON THE Ungodliness, By which the Glorious GRACE of GOD, is too commonly Abused.”

“Can you in your Conscience think, that our Holy Savior is honored by Mad Mirth, by long Eating, by hard Drinking, by lewd Gaming, by rude Revelling; by a Mass fit for none but a Saturn, or a Bacchus, or the Night of a Mahometan Ramadam? You cannot possibly think so!”

When we consider these sentiments about religious celebrations at the beginning of colonization, it’s hard to believe that Easter looks like it does today, complete with pastel outfits, chocolate bunnies, egg hunts, and large family meals.

Fortunately, we have an abundance of archival records for tracking the changing attitudes toward Easter, from its re-emergence within the Presbyterian church after the Civil War to its modern iteration as a celebration for both the religious and secular communities alike.

Unfortunately, finding those sources can prove challenging without traveling to visit various religious archives throughout the country, which makes it nearly impossible for scholars to access them without a significant investment of time and money.

Gale’s Religions of America combines these primary sources into a single, easy-to-use digital archive. Within it, scholars will find more than 660,000 pages of content from various collections, including Utah and the Mormons, The Shaker Collection, and the American Religions Collection at the University of California, Santa Barbara.

Scholars can gain unprecedented insight through these extensive resources to track developments in religious thought in America from 1820 to 1990 through the lens of the people living in these times.

Let’s explore just a few of those resources and how they exemplify the metamorphosis of Easter in America.

Tracing Easter Through the Ages

If we start with the oldest archival records in Religions of America, we see a sustained absence of so-called “Mad Mirth.” Despite there being no formal laws prohibiting its observance, there are no publications about Easter. In fact, the first mention of the springtime celebration wasn’t until September 17, 1894, in a piece from the Latter Day Saints Millennial Star titled “The Resurrections of Christ”:“‘He is risen,’ was the joyful greeting of the angels to the mourning disciples on the first easter morning.”

“The Resurrections of Christ.” The Latter Day Saints Millennial Star, September 17, 1894, 597+. Religions of America (accessed January 24, 2024). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/BMBZYD838258419/ROAM?u=seoblogs&sid=bookmark-ROAM&xid=d85f4e7c.

Even then, there’s no talk of Easter as a celebration or official holiday—much less our modern traditions like egg hunts and chocolate treats. Even so, non-religious entities were adopting secular Easter practices, including the introduction of the annual White House Easter Egg Roll in 1878.

The less-than-warm welcome for the Easter season didn’t last long. The 20th century instigated a great upheaval as the American economy shifted from close-knit, agrarian communities to large-scale urbanization. As cities boomed, more Americans lived next door to a rising immigrant population, catalyzing the cultural exchange of Easter symbology.

Easter at the Dawn of a New Century

German immigrants first introduced the idea of the Easter bunny or “Osterhase,” an egg-laying hare, to America, and children continued their tradition of building nests in which the hare could lay “Ostereier,” or Easter eggs.

While these German populations were primarily confined to rural Pennsylvania before urbanization, the Progressive Era saw more immigrants arrive between 1900 and 1915 than in the previous 40 years combined. By 1910, more than 2.3 million German immigrants lived in the United States, many of whom settled in cities where they worked alongside Americans who may have never heard of the concept of an Easter bunny or eggs. Advancements in print media technology also led to the rise of German publications, which further spread these now well-known Easter traditions.

With the rise in cultural exchange, the religious reaction to these new ideas took on a few new faces.

Some religious communities, including Mormons, saw these Easter traditions as an affront to the solemnity of the holy day, as evidenced in the April 28, 1904, publication of The Latter Day Saints Millennial Star.

The piece “Easter at Jerusalem” describes the celebration of Eid-Al-Kabir or “the Big Feast” that ends the weeklong Lenten Fast leading up to Easter Sunday. The author states, “Greeks, Armenians, Copta, Assyrians, [and] Abyssinians celebrate Easter together according to Eastern time,” but dismisses their celebrations, stating, “The holy fire, which is said to be kindled annually on this occasion by the Holy Ghost, is the greatest fraud in all [C]hristendom.”

“Easter at Jerusalem.” The Latter Day Saints Millennial Star, April 28, 1904, 270. Religions of America (accessed January 24, 2024). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/MZNSLN933619302/ROAM?u=seoblogs&sid=bookmark-ROAM&xid=e1bd7d5b.

Nonetheless, the association of the rebirth of Jesus and the earth became increasingly entangled—even within more traditional religions. Elder Wilford A. Beesley writes:

“Everywhere is joy and pleasure and beauty seen, and on all sides may be heard the warblings of our feathered songsters from the shady woods. Mother Earth indeed seems ‘born again.’”

Easter at the Cross-Section of Occult and Christianity

The world was in absolute turmoil as the 20th century wound on, with the first half rocked by the Spanish influenza epidemic, the Great Depression, and two World Wars. The deaths of hundreds of thousands in Nagasaki and Hiroshima and the subsequent arms race with the USSR only further contributed to the nation’s collective anxiety as global powers flexed their own ability to participate in “nuclear diplomacy.”

Occult thought became increasingly appealing to Americans as they grieved their losses and lived with the traumas of war. Many sought answers from non-traditional religious sources, which promised deeper meaning and greater connection with the divine through alternative practices that fell outside the teachings of mainstream Christianity.

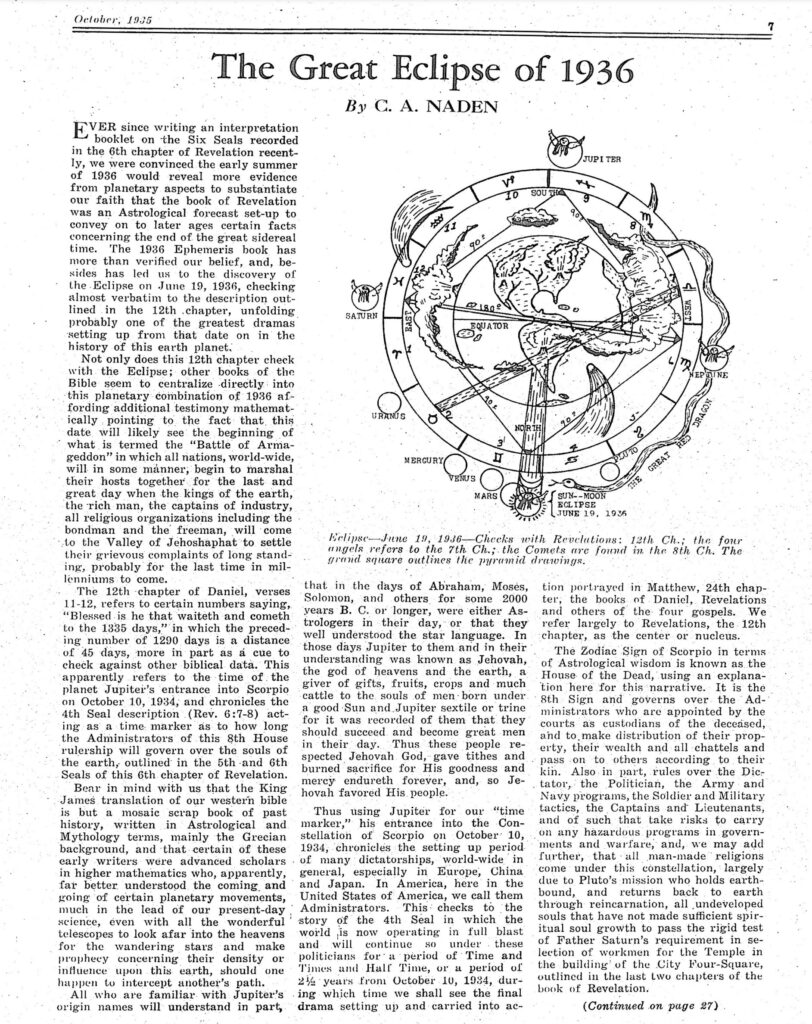

Periodicals like The Occult Digest only continued to build on the relationship between Judeo-Christian religions and emerging ideas like astrology. In their October 1935 issue, contributing writer C.A. Naden discusses predictions about The Great Eclipse of 1936 based on the 40 days that Christ spent with his disciples after the resurrection.

Naden, C. A. “The Great Eclipse of 1936.” The Occult Digest, October 1935, 7+. Religions of America (accessed January 24, 2024). https://link.gale.com/apps/doc/NFRWIT967264296/ROAM?u=seoblogs&sid=bookmark-ROAM&xid=0c5db71a.

The author starts by adding 40 days to Easter Sunday, which fell on April 12, 1936, bringing us to May 22. They then tack on an additional 13 days to account for the Bible being written under the Julian calendar, leaving us on June 5—just two weeks before the actual eclipse.

Naden argued that this prediction is evidence of traditional Biblical knowledge and occult astrological knowledge working in partnership rather than opposition: “The Eclipse on June 19 at the New Moon and this descriptive story of Revelation 12th chapter, shows how close these early Astrologers were able to record time and events of a future day when Jesus would come in like manner as He was seen to go.”

Another example—not to be confused with the Jim Jones cult The People’s Temple— is the Temple of the People, a theosophical group that formed in 1875 in New York before moving to California, where they grew their ranks of members interested in the cross-section of religion and mysticism.

In their February-March 1943 publication of The Temple Artisan, one author writes of the Easter resurrection not only of Jesus but also of every human being:

“Then, and only then, can come [the spiritual soul of man’s] real Easter Day, its day of Resurrection from the dead, the day when the Christ in man has brought a realization of all his pre-existences in form and the indivisibility of the One Life underlying all manifestation . . . Let no Easter Day pass without bringing forward for thought and meditation the great promise of the dawn of a new life, a new spring for the soul.”

We see in this writing a certain sense of optimism and power of self, an appealing sentiment for those who craved a connection with spirituality but sought meaning outside the church’s traditional teachings. It spoke to people who wanted a sense of control over who they were and who they could become, not limited by a single life and ultimate judgment after death.

Measuring Easter’s Modern Impact

The celebration of Easter did not stop evolving after World War II.

As time marches on, we see church groups hosting Easter events rather than condemning them, accepting that one of the best ways to get people in pews is to embrace the more recreational aspects of secular traditions. A 1950 newsletter from The Foundation Faith of God in Atlanta, Georgia, invited congregants to join them for a “Celebration of Rebirth,” after which children of all ages could gather for an Easter egg hunt.

More recently, Christian publications have presented a scholarly approach to religious questions by recognizing the influence that non-Christian religions had on Easter rather than rejecting them altogether. A March 1989 edition of The Kingdom Courier includes an essay called “The Passover and Easter/Resurrection!” that explores the relationship—or lack thereof—of pagan celebrations of the vernal equinox, the Jewish observation of Passover, and the Christian focus on the crucifixion and resurrection of Christ.

“Kingdom Courier March, 1989 Issue 3 Volume 6.” Kingdom Courier, vol. 6, no. 3, Mar. 1989, pp. 1+. Religions of America, link.gale.com/apps/doc/HDCDTH782618418/ROAM?u=seoblogs&sid=bookmark-ROAM&xid=f68c8779. Accessed 24 Jan. 2024.

When we stack these resources next to Cotton Mather’s impassioned speech on the sins of merrymaking, it’s much easier to see the distinctly American flavor of modern Easter. They exemplify how deeply our nation intertwines commercialization, religion, secular belief, and cultural context to build our traditions, and how often far-off and foreign ideas inspire our own celebrations.

As the only archive of its type, Religions of America stands out as the most accessible way to conduct such longitudinal studies of Easter and other American religious traditions. It’s invaluable in its scope for scholars of all types—theologians, anthropologists, historians, psychologists, and more—making it a must-have resource for any collegiate library.