Isaac Newton was born on Christmas Day 1642, a sickly child in a country divided by civil war. His father had died months before his birth, and his mother’s remarriage soon took her away, leaving Isaac behind under his grandparents’ care.

His childhood on a remote Lincolnshire farm was worlds away from the scholarly circles he would eventually join—yet from those quiet beginnings emerged the mind that revealed how motion, light, and gravity govern the universe.

Explore the life and work of Isaac Newton—as well as those of his contemporaries—using the Gale In Context suite of databases. Gale In Context: Biography shows where Newton’s persistence began—how his surroundings and experiences shaped his approach to questions about the natural world. Gale In Context: Science traces how his inquiry took shape in studies of motion and light, culminating in the principles that still define modern physics.

Together, these two databases offer a comprehensive view of Newton’s life and his determined work to find order in the natural world. Let’s first look at Newton’s upbringing and life before turning to his scientific work.

Setting the Stage for Modern Science

When Isaac Newton was born, science was not yet a formal discipline. Scholars called their work natural philosophy—a broad study of the physical world that mixed observation with speculation about purpose and design. Much of it followed Aristotle’s teachings, which held that knowledge could be reached through reasoning alone.

When a stone fell to the ground, an Aristotelian philosopher would have said it was returning to its natural place. Fire was thought to rise because its nature drew it upward, while heavy objects fell because their nature pulled them down. These patterns seemed self-evident and, through reasoning, were taken as proof that everything in the universe moved according to purpose and design. Because the explanations fit neatly together, few felt the need to test whether nature actually worked that way.

By the early 1600s, however, a small group of thinkers began to challenge that tradition. Their insistence on experiment over assumption laid the intellectual groundwork for Newton’s lifetime—and for the scientific method itself.

Some of the thinkers who helped shape the scientific world that Newton inherited included:

- Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543): Put forward the heliocentric theory, arguing that the Sun—not Earth—was the fixed center of the solar system.

- Johannes Kepler (1571–1630): Analyzed astronomer Tycho Brahe’s observations, with which he discovered predictable celestial motion as planets travel in elliptical orbits.

- Galileo Galilei (1564–1642): Used telescopes to observe moons orbiting Jupiter, providing direct evidence that not everything revolved around Earth—a finding that challenged centuries of geocentric belief.

- Francis Bacon (1561–1626): Argued that inquiry should begin with observation and experiment—the foundation of the modern scientific method.

- René Descartes (1596–1650): Described a mechanical universe governed by laws of motion and expressed through mathematics.

- Robert Boyle (1627–91): Conducted repeatable experiments in controlled settings, setting a new standard for proof in chemistry and physics.

Gale In Context: Biography situates each thinker within the social and philosophical tensions of their age—what they read, who they debated, and how their ideas took shape. Gale In Context: Science builds on that foundation with interactive content, primary sources, images, videos, and experiments that invite students of all learning styles to explore scientific ideas in greater depth.

The Making of a Modern Thinker

Newton spent much of his childhood alone, occupied with repairing small tools and building contraptions from whatever materials he could find. He even constructed a little windmill that turned when a mouse ran inside. He also showed an early aptitude for experimentation, taking methodical notes as he observed the wind catching the sails of a paper boat or the shadows moving across his hand-etched sundials.

When his stepfather died, Newton’s mother returned home with her younger children and removed Isaac from his boarding school in Grantham, bringing him back to full-time work on his grandparents’ farm.

But Newton proved an inattentive farmer, prone to daydreams and long stretches of tinkering while chores went unfinished. His uncle and former headmaster eventually convinced his mother to let him resume his studies at the King’s School, where his mechanical curiosity and appetite for learning quickly reemerged.

Studying in Solitude

Newton entered Trinity College, Cambridge, in 1661 as a subsizar, working for wealthier students to cover his expenses. The curriculum he encountered was still built around Aristotle’s natural philosophy. Newton studied it carefully but found it unsatisfying. He preferred problems that could be solved, not merely reasoned about.

He began reading the newer works that students passed among themselves, from earlier minds like Kepler and Galileo. His tutor, Isaac Barrow, noticed his ability and gave him access to advanced texts in mathematics and optics, the branch of science concerned with the properties of light.

When the Great Plague of London reached Cambridge in 1665, Newton returned to Lincolnshire with a chest of books and instruments. He capitalized on his break from school to try out his own experiments, using glass prisms to split sunlight into its individual colors and writing equations that described changing quantities in an early version of calculus. Those private studies, carried out in near isolation, produced the first outlines of the theories that would later make him the central figure of modern physics.

When the plague subsided, Newton returned to Cambridge in 1667 and resumed his studies. That same year, he was elected a fellow of Trinity, and two years later, he succeeded Isaac Barrow as Lucasian Professor of Mathematics, one of the most prestigious academic posts in England.

The Royal Society: Where a Sharp Mind Wielded a Sharp Tongue

Founded in 1660 under King Charles II, the Royal Society was Britain’s first national scientific academy. Its motto, Nullius in verba—“take nobody’s word for it”—captured its purpose: to pursue evidence rather than rely on authority. Newton’s election as a fellow in 1672 placed him at the center of England’s growing network of cutting-edge thinkers.

Newton was a well-admired intellectual among his peers, but he also earned a reputation for being difficult. He was quick to take offense when someone questioned his ideas, which led to a series of famous—and sometimes brutal—academic feuds.

His earliest dispute was with Robert Hooke, who claimed Newton had borrowed his ideas on light and gravity. Newton fired back in print, dismissing Hooke’s theories as little more than conjecture, and adding the now-famous line, “If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants.” The remark may well have been a sly insult: Hooke was short and hunchbacked.

His relationship with Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz was no kinder. When Leibniz requested that the Royal Society investigate who had invented calculus first, Newton—by then its president—anonymously wrote the committee’s “independent” report, declaring himself the rightful discoverer. So furious was Newton about this case of “plagiarism,” that after his rival’s death, he reportedly wrote to a friend that he took great satisfaction in “breaking Leibniz’s heart.”

Despite the turmoil, Newton’s influence within the Royal Society only grew. His research on light and color and his invention of the reflecting telescope had already earned him recognition. Further, the 1687 publication of Philosophiae Naturalis Principia Mathematica made him a figure of unquestioned authority. In it, he defined the three laws of motion, showing how inertia, force, and action/reaction govern all movement, and unified celestial and terrestrial mechanics under a single theory of universal gravitation.

The Great Ocean of Truth: Newton’s Scientific Discoveries

Newton once compared himself to “a boy playing on the seashore . . . finding a smoother pebble or a prettier shell than ordinary, whilst the great ocean of truth lay all undiscovered before me.” That sense of wonder—paired with his relentless insistence on mathematical proof—shaped the way he approached every scientific question.

Gale In Context: Science invites students to interact with Newton’s discoveries and explore how those principles continue to support modern scientific practices.

Light, Color, and Optics

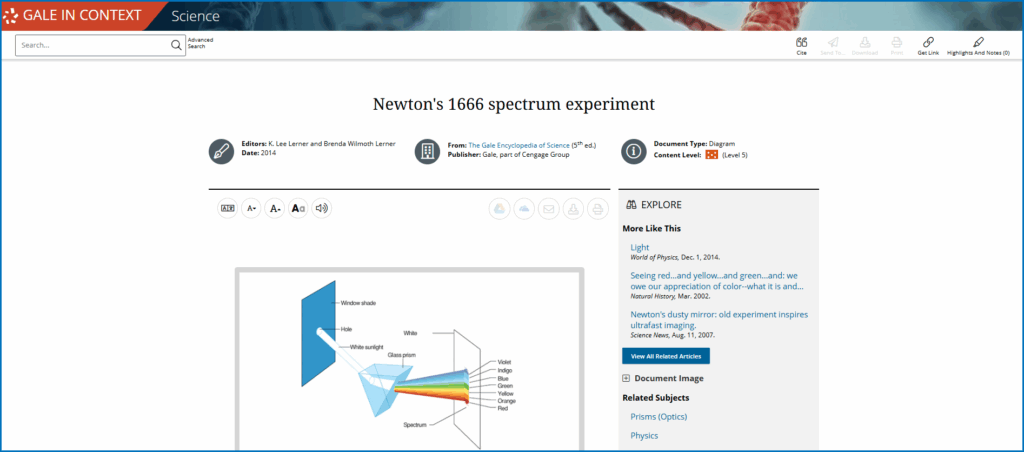

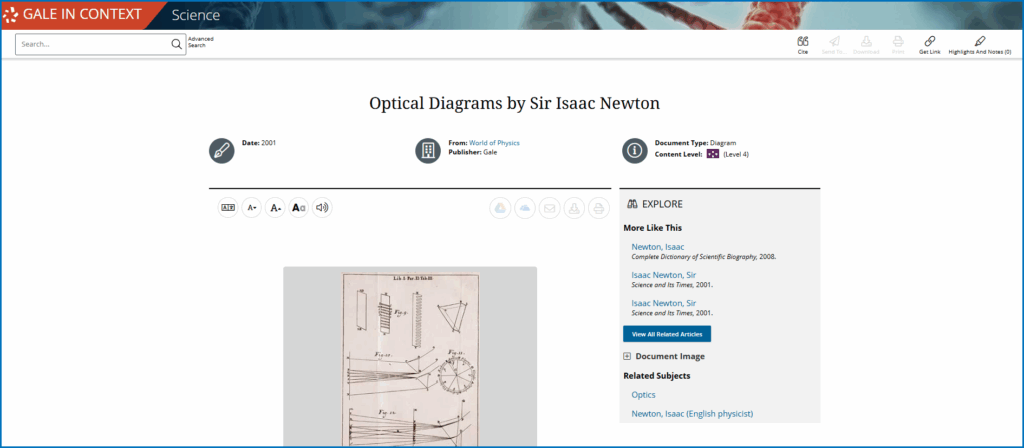

Newton began experimenting with optics during his years in rural Lincolnshire by sending a narrow beam of sunlight through a glass prism. The light fanned out into a strip of colors—red through violet—rather than staying white. From that result, Newton concluded that white light already contained the full range of colors, and the prism’s shape separated them according to how each one bent as it passed through the glass.

Newton went on to demonstrate this by recombining the separated colors with a second prism to recreate white light, experiments that formed the basis of his theory of color.

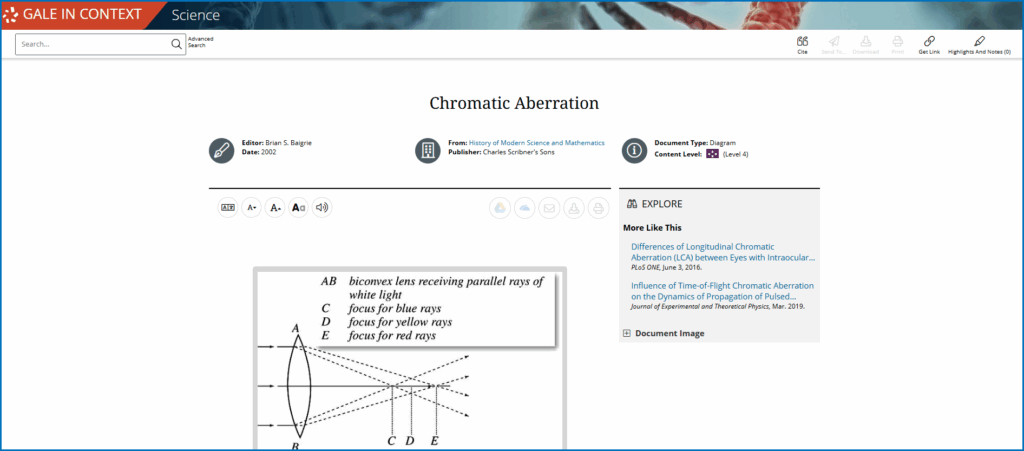

He also used what he learned to improve upon the telescope. Traditional refracting telescopes used lenses to bend incoming light, but because each color in white light bends by a slightly different amount, the image never came into perfect focus. This phenomenon produced colored fringes—an effect called chromatic aberration.

Newton reasoned that the only way to avoid the problem was to stop using glass lenses altogether and instead use a curved mirror to gather and focus light, rather than bending it through a lens. Mirrors reflect all wavelengths equally, so the colors stay aligned and the image appears sharp.

Rewriting the Rules of Motion

Aristotelian philosophers believed that for motion to exist, an object must be acted on by a continuous force. So, when an arrow flew, it was because the air was rushing in behind it, literally pushing it forward.

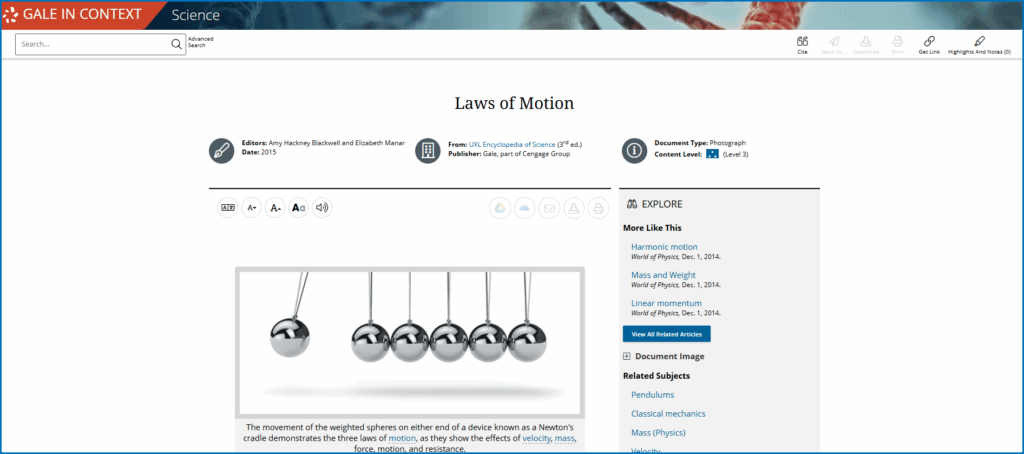

Newton approached the problem from a different angle—imagining how objects would move without friction or air resistance. These observations became Newton’s laws of motion.

The First Law of Motion

Conducting experiments with pendulums, colliding balls, and objects sliding on smooth surfaces, Newton noticed that motion persisted until something interfered with it. That realization became his first law: An object at rest remains at rest, and an object in motion continues in a straight line at a constant speed unless an outside force alters its state. Newton called this resistance to change inertia, the built-in tendency of a body to keep whatever state of motion it already has.

Once Newton recognized inertia as a basic property of matter, he was able to explain how a puck would glide a shorter distance on grass than on ice, for example, since grass creates more friction to counteract the puck’s inertia.

The Second Law of Motion

To understand how motion changes, Newton examined acceleration—how quickly a body’s speed or direction shifts. His second law showed that this change is directly proportional to the force applied and inversely proportional to the object’s mass, a relationship expressed as F = ma. A small force produces a noticeable acceleration in a light object. In contrast, the same force barely affects a heavy one. That is why stopping a rolling car is nothing like stopping a rolling soccer ball: the car’s greater mass means its motion changes far more slowly under the same applied force.

The Third Law of Motion

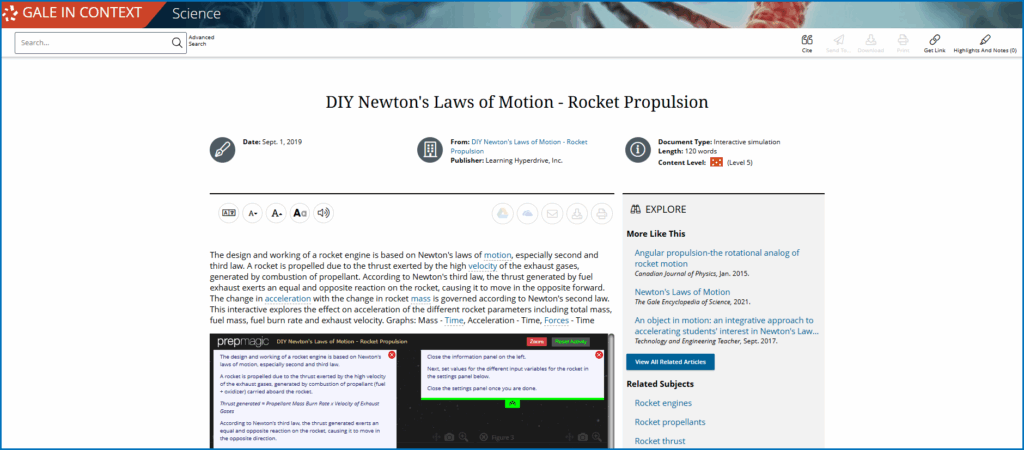

His third law states that every force comes in pairs. If one body exerts a force on another, the second body exerts a force on the first, equal in magnitude and opposite in direction. Two skaters pushing off from the same spot glide apart because they experience forces at the exact moment of contact. Similarly, a cannon recoils as its shot flies forward, and a rocket rises because its exhaust is forced downward.

Gravity and the Mathematics of Change

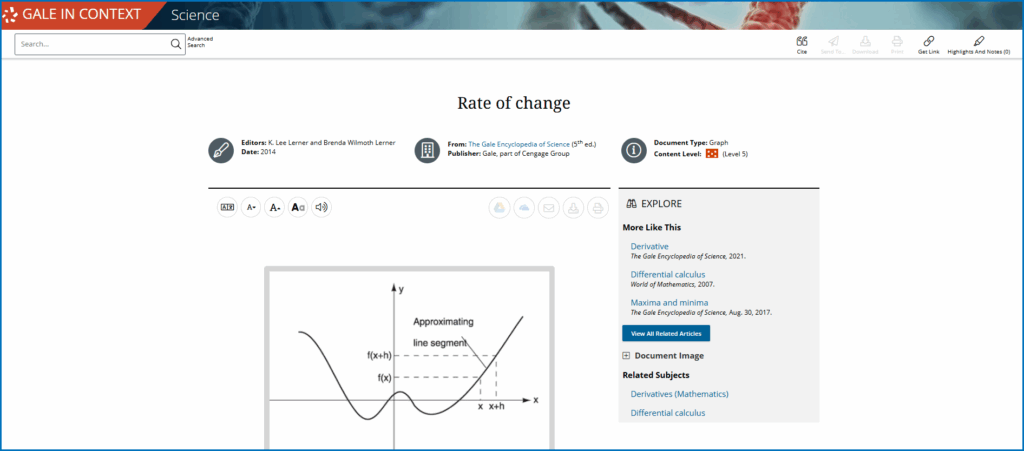

To describe the natural patterns Newton observed in forces and light, he needed a mathematical language capable of handling continuous change over infinitesimally small intervals in time, a field we know today as calculus.

In his private notebooks, Newton developed what he called fluxions, methods for describing how quantities change from moment to moment and projecting broader extrapolations based on that data.

For example, if he timed how far a dropped ball fell in one tiny slice of time, he could work out its exact speed at that instant. When he checked the ball again an instant later and saw that it was falling faster, the change in speed revealed how strongly gravity was pulling on it. By watching those tiny changes accumulate, he could trace the ball’s entire motion from release to impact.

Newton realized he could use the same math to study anything whose motion changed. So he looked upward, relating how the Moon’s position changed over time to the pull that must be acting on it. Newton treated it much like a ball—an object whose speed and acceleration he could work out from regular, repeated observations.

When he compared the Moon’s acceleration to the pull of gravity measured here on Earth—about 9.8 m/s²—the relationship made sense. The Moon’s inward acceleration—the pull that continually bends its path into an orbit—is only about 0.0027 m/s², roughly 1/3600 as strong as gravity at Earth’s surface. In other words, if you could measure how quickly the Moon “falls” toward Earth each second, that fall is just fast enough to keep it in a curved path rather than sending it drifting away.

Since the distance to the Moon is around 60 Earth radii away from the surface, the numbers matched the inverse-square pattern he expected. Gravity weakens with distance, and at sixty Earth radii, it should be about 1/3600 as strong. It was strong evidence that the force pulling an apple downward was the same force governing the Moon’s orbit.

From this, he concluded that motion on Earth and motion in the sky followed one set of rules—Newton’s law of universal gravitation—a connection that gave scientists a unified way to understand everything from falling objects to orbital paths.

Newton’s drive to connect different parts of the natural world changed how people approached scientific problems. Aristotelian thinkers started with assumptions about how things ought to behave. Newton insisted on explanations that matched observable, measurable, and repeatable results. He worked from what he could see and quantify, then used those relationships to uncover patterns that reached far beyond the immediate experiment.

We’ve only waded ankle-deep into the “great ocean of truth” that is Newton’s life, his scientific work, and the world of thinkers who shaped it. Gale In Context: Biography and Gale In Context: Science invite students deeper, pairing the story of his life with his insistence on evidence-based reasoning that continues to anchor modern scientific practice.

Bring these perspectives into your classroom by reaching out to your local Gale sales representative. They can walk you through how the Gale In Context suite works together to help students connect the lives of major thinkers with the ideas that shaped their fields.