| By J. Robert Parks |

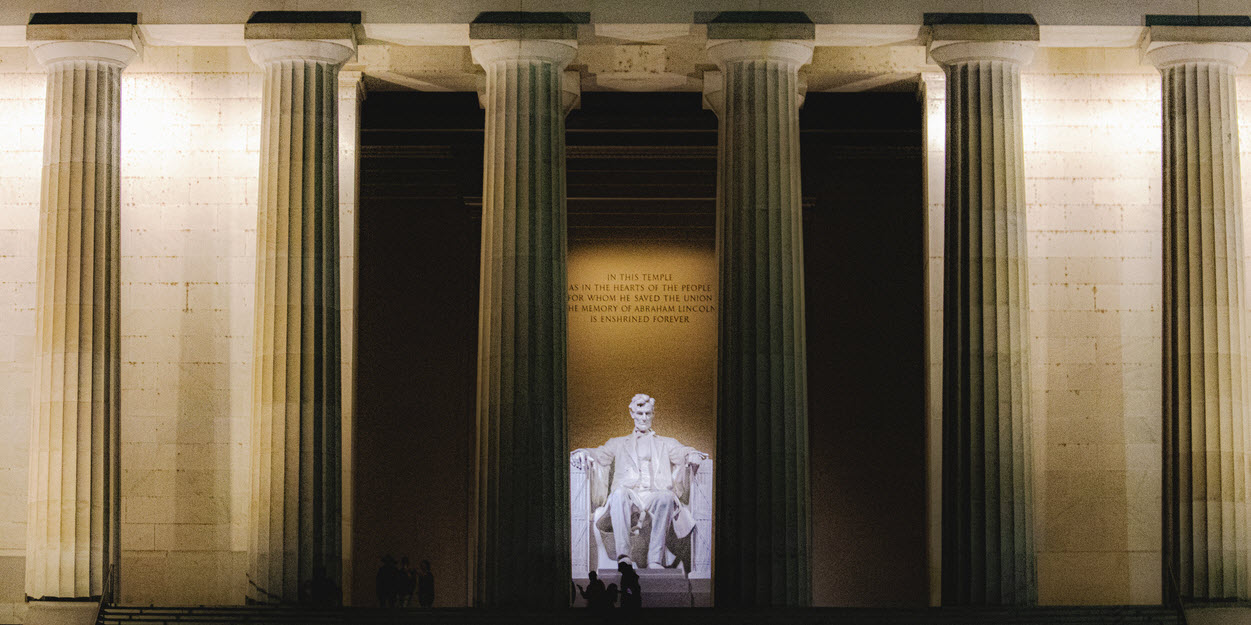

Gale In Context: U.S. History contains coverage of iconic U.S. landmarks, including the Lincoln Memorial in Washington, DC, which celebrates the centennial of its dedication this month. A monument for President Abraham Lincoln was first proposed in 1867, just two years after he was assassinated, but a lack of funding delayed its building for more than 50 years. Congress finally approved funding in 1910; construction began in 1914; and it was dedicated and opened to the public 100 years ago this week, on May 30, 1922.

The Lincoln Memorial is an impressive structure, designed to look like a classic Greek temple―which is fitting, as ancient Greece is regarded by many historians as the birthplace of democracy. It uses two rows of columns to divide the interior into three sections, and the center section features a 19-foot-tall marble statue of Lincoln on a 10-foot pedestal. The two outer sections have carved inscriptions of two of Lincoln’s most famous speeches: his second inaugural address and the Gettysburg Address. Both have been studied by students for more than a century, and reading them in that majestic setting is inspiring. The 87 steps leading from the reflecting pool are an intentional nod to the “Fourscore and seven years” referenced in the Gettysburg Address.

There was some controversy over the original plan for the Lincoln Memorial, especially its placement at what was then a swamp in West Potomac Park, some distance from the Washington Monument and Congress. The site’s designers, however, thought having the memorial on the line from Congress to the Washington Monument suited the memorial and gave the area a beautiful symmetry as part of a growing civic space. Since its dedication, other memorials have been situated near the Lincoln Memorial, including the Vietnam War and Korean War memorials.

While the Lincoln Memorial has been a favorite destination for tourists since its dedication, it has also been the site of numerous notable historic events, including the delivery of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s famous “I Have a Dream” speech. As part of the landmark March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, King’s speech was a pivotal moment in the civil rights movement, helping to drive its message of hope and possibility deeper into the national consciousness.

That wasn’t the first event related to civil rights to be held at the Lincoln Memorial. On April 9, 1939, the legendary Black singer Marian Anderson gave a free recital on the steps of the Lincoln Memorial before an interracial crowd of 75,000 people. Anderson had been barred from performing at Washington DC’s Constitution Hall by the organization Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR). Although the DAR was a patriotic organization, it had prohibited Black artists from performing at Constitution Hall because some of its members had complained that Black and white people were seated together at some events. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt was outraged and sent a letter resigning from the organization, and the federal government then invited Anderson to sing at the Lincoln Memorial instead.

One of the most unusual events to take place at the Lincoln Memorial happened in May 1970 when President Richard Nixon impulsively went there in the middle of the night and ended up talking to anti-war protestors and even taking photographs with them. A few days later, he wrote a vivid memo to his chief of staff justifying why he went and explaining his version of events.

The memorial’s dedication itself is worth remembering as a reminder of how strained race relations still were at the time of the event. Although many Black Americans had been invited to the ceremony, they found out when they arrived that the seating was segregated. Black attendees had to sit separately from the white audience. It was an indication that although Lincoln had helped abolish slavery, the cause of racial equality still had significant ways to go. In fact, emancipation and the end of slavery are only referenced on the memorial’s walls in Lincoln’s own quoted speeches, not in any general or contextual way at the site.

Meet the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale InContext: U.S. History and Gale InContext: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.