| By Andrea Drouillard |

“You will never truly know yourself, or the strength of your relationships, until both have been tested by adversity.”

This quote by J. K. Rowling rings true for me. I firmly believe that true empathy cannot exist without experiencing hardship. Facing adversity head on is a way of life for my husband and me. We are seasoned veterans.

In 1994, Chris and I planned to get married. The wedding was set for September. In June, his body went numb on one side. It wasn’t a stroke, yet doctors could not figure out what happened. They diagnosed everything from acid reflux to TMJ. No stranger to challenges (he made it through a broken back due to a water skiing accident when he was 14 and a malignant tumor on his spinal cord diagnosed when he was 15), Chris rose to the occasion and taught himself to walk again after the incident in June. He walked down the aisle at our wedding with a cane, but he walked.

In 1999, we were expecting our first child when mobility became more challenging for him. We chalked it up to all the trauma his body had been through with the accident…and the cancer. We adjusted. He started to use a shower chair. Always seeing a glass half full, he looked at using a shower chair as an opportunity to recline and chill out in an extra long shower while listening to his favorite music. A week before our daughter was born, he was officially diagnosed with MS.

I remember our reaction: “Okay. We can deal with this. It’s only MS.” Blissful ignorance. Our daughter was born, and we were thrilled and grateful and enjoyed the first couple years of her life as normally as possible.

And then Chris started to fall. He fell a lot. He fell in the morning. He fell at work. He fell when got home from work. We were on a first-name basis with every man at the fire department. Non-emergency calls for help were the norm for us, and we felt like the men at the fire department were an extension of our family. Our daughter was used to seeing Chris on the floor more than on his feet. We normalized it. I would sit him up against a wall and we would sit together and read or sing or play. And wait for the fire department. Disability dramatically changed the lens through which we looked at and responded to life.

September 11, 2001. I will never forget how beautiful that morning was. I remember making a mental note to be grateful for such a clear, sunny, beautiful morning. But when I got to work, the world changed. Planes were flying into the towers and the towers fell. I left my office, picked up my daughter from daycare, and headed toward home to figure out what would happen next. Little did I know that when we got home, I would be faced with a husband in the middle of an unrelenting MS episode. His body revolted; everything stopped working. The ambulance came. I sat in the ER watching the reports about 9/11 and pondering the future. September 11, 2001, was the last day he walked.

I couldn’t give up—I was suddenly the sole bread winner in our home with a daughter to raise and a new title: caregiver. Crying in a corner in fetal position wasn’t an option. We couldn’t give up; there is no safety net for people who are suddenly unable to work or care for themselves.

Over the years I have developed a heightened awareness about how society treats people with disabilities. His friends went on with their lives—without Chris. People often don’t look him in the eyes. They talk to me instead of him when ordering at restaurants. When they do talk to him, they talk loudly. Yes, he’s tetraplegic…but he can still hear and respond. Timers aren’t set properly on automatic door openers at theatres and museums, so his hands get crushed and his chair gets caught. People rush around him in crowds making it even more complicated to find a clear path to exit movies and concerts. We always have to be thinking and planning steps ahead to do something as simple as go to dinner.

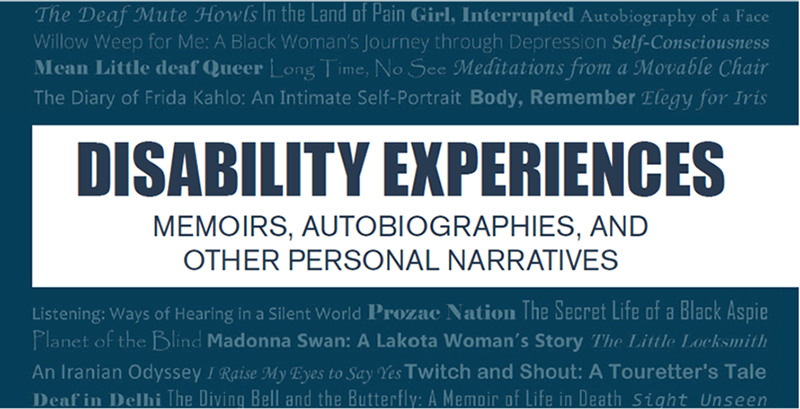

All these experiences and so many more are my reasons for being excited that Disability Experiences (DEX) has been brought to life. The special value of DEX is that it offers critical access to personal representations of the experience of various conditions from Alzheimer’s to schizophrenia. It will be useful in emerging fields such as medical humanities, which will play a critical role in medicine and create a more empathetic and humanistic clinical experience for people like Chris.

When I watched the news recently, I saw that kind of empathy in Jon Stewart’s response as he tearfully pled with Congress to continue funding the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund. He has seen first-hand the outcomes of their bravery on that day: cancer, respiratory issues, autoimmune disorders, mental health conditions, and more. He gets it. “We need to continue fighting,” he said. Indeed.

If this post prompts you to make a small change like holding the door for someone, or a bigger change like getting involved in intersectional disability activism, I believe it will make the world a little nicer, and a more empathetic place.

Learn more with Disability Experiences: Memoirs, Autobiographies, and Other Personal Narratives, 1st Edition >>

Meet the Author

Andrea Drouillard is a sales director for K12 and public library markets at Gale. She’s a mom, music lover, lipstick hoarder, gardener and street art enthusiast who is always happiest by the water.