| By Chilton Staff |

In the 1940s, Ralph R. Teetor patented an early method of cruise control—a key part of autonomous vehicles. Despite being blind, Teetor was a visionary who obtained more than 40 patents during his lifetime.

“Boy Genius”

Ralph Rowe Teetor was born in 1890, when the work of harnessing electricity and building automobiles was in its infancy. His family’s business had evolved with the times, transitioning from bicycles to railroad inspection cars, and working with tools was part of Teetor’s upbringing. When he was using a knife to open a drawer at age five, the knife slipped and blinded him in one eye. The subsequent infection left him blind in both eyes within a year.

Teetor’s family preferred not to talk about his blindness and expected that he would live a full life with many achievements. He keenly persisted in his interests in electricity and automobiles, and his father built him a fully equipped shop. By age 12, Teetor was called a “boy genius” in newspaper articles published across the United States—many of which never mentioned his blindness.

At 12, he was considered the “youngest successful electrician in the world” according to a report from The Cincinnati Enquirer, often astounding other electricians by correctly answering every question that was thrown at him. 1

It is the delight of this young mechanic to make something useful that will be of practical and daily use. His latest scheme was to equip his father’s house with complete electric lighting, operated by his gasoline engine in the shop. [It was the first house in the town with electric lighting.]

About a year ago Ralph became interested in the subject of automobiles and built one for himself. It proved a success in every particular. 2

Teetor did not use a cane, instead relying on memory to navigate. He counted the steps to places like the barbershop, knew the bushes along the way, and was guided by scents and sounds to safely cross the streets of his small town of about 2,000 people.

He developed an exceptional ability to visualize objects and distances. For example, Ralph helped build and install the basketball hoops at his high school and this was enough for him to be able to amaze his friends by sinking basket after basket. 3

“First Blind Person to Receive an Engineering Degree”

Remarkably, Teetor was the first blind person to obtain an engineering degree at the University of Pennsylvania, and according to some, he was first in the entire United States.4 After being turned down by the University of Michigan, Teetor persuaded the dean of the University of Pennsylvania’s engineering department to accept him as a student, though the dean didn’t expect Teetor to last more than a couple of weeks. 5

With the assistance of his cousins who also attended the school, Teetor did very well. His cousins read the textbooks to him, and Teetor (who had taught himself to type) was able to write papers as well as edit the engineering club newspaper. He ultimately earned a master’s degree in mechanical engineering, and in later years was awarded honorary doctorates.

According to his nephew, Jack Teetor, Ralph Teetor opened the door for future engineers with disabilities to attend college and be hired by auto manufacturers. 5

Inventions

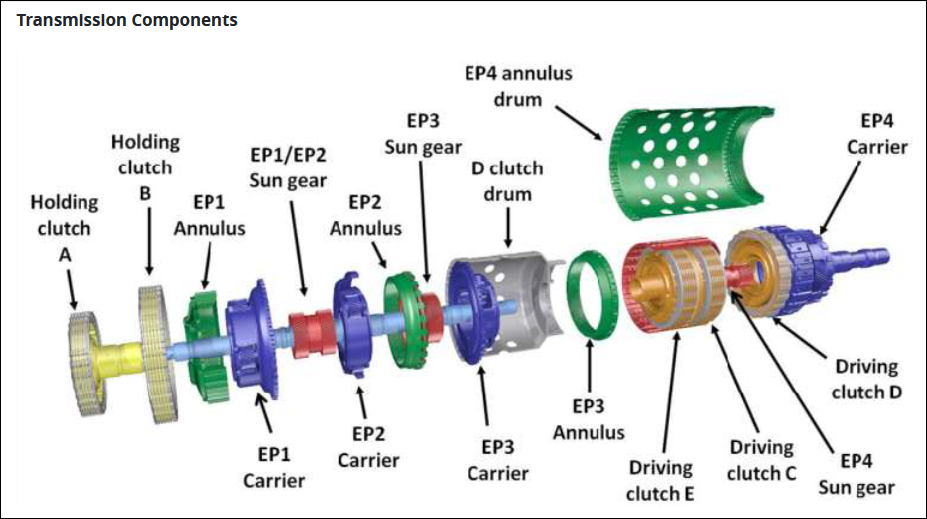

In all, the U.S. Patent Office granted Teetor more than 40 patents, including for a type of cruise control. Teetor also patented a gear shift, which he sold to the Bendix Corporation in the 1920s. Automakers, however, didn’t think the public would be interested in shifting gears automatically—but Ralph Teetor was clearly ahead of his time. It was not until 1946 that automatic transmissions appeared in mass-produced vehicles, when GM’s Hydramatic transmission debuted.

The Teetor family business began to specialize in manufacturing piston rings, renaming itself “Perfect Circle.” Ralph Teetor improved the piston ring technology of the time, receiving several patents for that as well.

During his career at Perfect Circle, Ralph often used his sense of touch to accurately judge the size of mechanical components, one time declaring a piece too large by a couple thousandths of an inch. After some scrambling for a measuring instrument by peers, he was found to be correct. 1

Cruise Control

Though types of speed governors were in use back in the 17th century with steam engines, in the early years of the automobile, the emphasis was on improving roads and vehicles in order to travel faster. No one was thinking of limiting speed.

Ralph Teetor started thinking about how to build a mechanism that would maintain a consistent speed because of one of his drivers—his lawyer. When his lawyer drove, the ride was very jerky. The lawyer had a habit of slowing down when he was talking and then speeding up whenever Teetor spoke. Teetor thus began working on a speed control device in the 1930s, calling it a “speed-o-stat.”

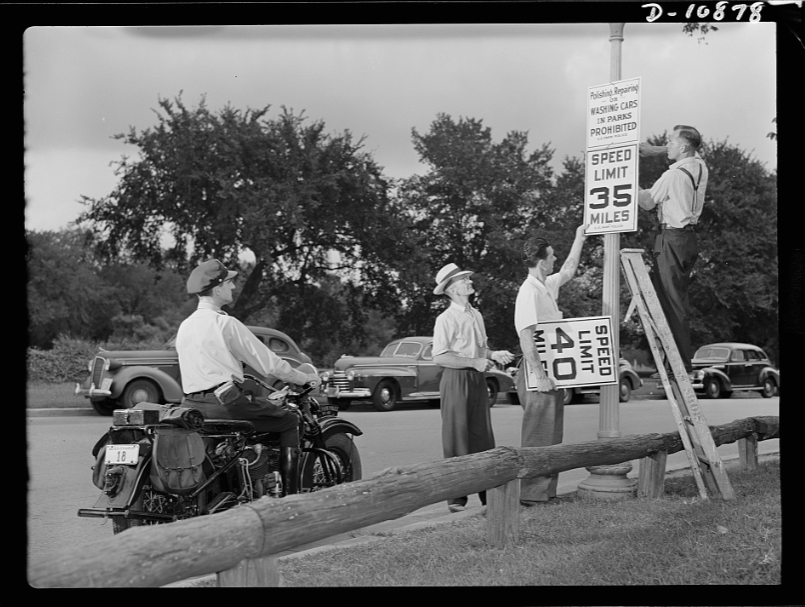

During World War II, the Office of Defense Transportation instituted “Victory Speed” to save gas and tires. The temporary law prohibited driving faster than 35 mph. Though compliance was low, Victory Speed created public awareness of speed control and its benefits. Besides gas and tire savings, slowing down also proved to be safer.

Teetor continued to refine the speed-o-stat and, in 1958, Chrysler was first to offer the new technology on a few models, calling it “Auto-Pilot.” In 1959, Cadillac called theirs “Cruise Control.” Today, cruise control is standard and a precursor of adaptive cruise control. Both are key components of autonomous driving.

ChiltonLibrary Accessibility

According to the American Foundation for the Blind, an estimated 50 million American adults, age 18 and older, reported experiencing some degree of vision loss. 6 The Centers for Disease Control reports that people with disabilities make up about one quarter of the US population. 7

ChiltonLibrary accessibility tools aid users in accessing auto repair procedures. For example, text customization tools allow users to enlarge text, change fonts, and switch colors, and the text-to-speech feature reads repair procedures aloud in English as well as in other languages.

If your library doesn’t currently subscribe, take ChiltonLibrary for a cruise to discover its many features.

Notes

1 Matt Graham, with additional contributions from Whitney Pandil-Eaton, Rebekah Oakes, and Julianne Simpson, “A Brilliant Touch,” United States Patent and Trademark Office.

3 William S. Hammack, How Engineers Create the World: Cruise Control, Articulate Noise Books, 2011, pg 185.

4 National Inventors Halls of Fame, “Ralph Teetor: Cruise Control U.S. Patent No. 2,519,859, Inducted in 2024, Born Aug. 17, 1890 – Died Feb. 15, 1982.”

5 Brian Yopp, Many Voices, One Story: “Blind Logic: The Ralph R. Teetor Story” interview with Jack Teetor, MotorCities National Heritage Area, June 4, 2024.

6 2022 American Foundation for the Blind national health interview survey.

7 Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Disability and Health Data System (DHDS) [Internet]. [Updated 2024 July; cited 2024 October].

Additional Reading/Study

- Blind Logic documentary, a Jack Teetor film.

- Brendan McAleer, “Ralph Teetor: The Blind Visionary Who Invented Cruise Control,” Automotive History, Maintenance and Tech; People, Hagerty Media, 20 September 2024.

- David Sears, “The Sightless Visionary Who Invented Cruise Control,” Smithsonian Magazine, March 8, 2018.

- Experience Michiana, PBS Michiana – WNIT, interview with Ralph Meyer, grandson of Ralph Teetor, July 18, 2024.

- Frank Rowsome Jr, “Educated Gas Pedal,” Popular Science, Jan. 1954, Vol. 164, No. 1 Pg 168.

- Marjorie Teetor Meyer, One Man’s Vision: The Life of Automotive Pioneer Ralph R. Teetor, Guild Press, 1995.

- Motor Age (Vol. 49), 1926, United States: Class Journal Company (Chilton), pg 42.

- “Ralph Teetor and the History of Cruise Control,” American Safety Council blog.

- SAE International Educational Award Honoring Ralph R. Teetor.

- “Science: I See,” Time Magazine, January 27, 1936. https://time.com/archive/6891472/science-i-see/

- Walter P. Reuther Library, Wayne State Michigan, photograph: Perfect Circle Strike, Local 156, Hagerstown, Indiana, 1955.

- United States Congress, Senate, Select Committee on Improper Activities in the Labor or Management Field, 1957.