| By Gale Staff |

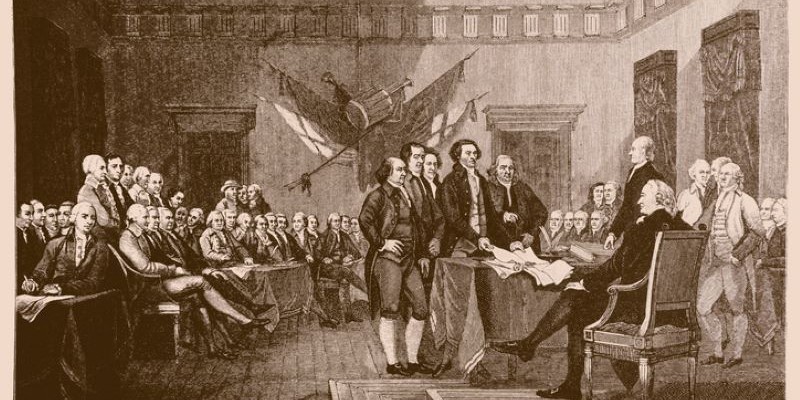

The American Revolution arguably receives the most attention when students are taught U.S. history, beginning with Paul Revere’s ride and the Declaration of Independence in elementary school to Thomas Paine and John Locke in high school and college. That’s likely to become especially true over the next several years, as the country celebrates the 250th anniversaries of numerous events. One of those anniversaries is this month—when delegates gathered in Philadelphia on May 10, 1775, for the opening of the Second Continental Congress. Appropriately, Gale In Context: U.S. History has a wealth of resources—including primary sources, in-depth analyses, and historical overviews—for educators and librarians looking to direct students to information about the Second Continental Congress and so many other aspects of the American Revolution.

Colonists in the 1770s weren’t necessarily eager to form any kind of congress. Many colonial leaders were suspicious of the other colonies, believing that those colonies wouldn’t have their best interests at heart. In other cases, colonists feared that forming a central government would lead to the same kind of oppression they were experiencing under British rule. Nonetheless, the lack of a collective government made it difficult for the colonies to advocate for shared interests against British governing and economic decisions. After Britain’s parliament passed what became known as the Intolerable Acts in the spring of 1774, many colonial leaders recognized that something needed to change.

The First Continental Congress met in Philadelphia on September 5, 1774, with representatives from 12 of the colonies (all but Georgia) sending delegates. Over the next seven weeks, the delegates argued over the course of action they should pursue. One of the most important actions the delegates took was issuing the Declaration of Rights and Resolves, which argued for the rights of colonists to assemble freely and to petition Britain for changes in its relationship with the colonies.

The First Continental Congress adjourned in late October and planned to reconvene in May 1775, hopeful that Britain would respond favorably to its demands. Instead, relations with Britain deteriorated even further, highlighted by the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775. When the delegates reconvened for the Second Continental Congress on May 10, they had to decide how to respond and particularly whether they should prepare for war.

One of the first major decisions Congress made was to create a colonial army and to appoint George Washington to lead it, which it did in mid-June. To finance the war, Congress also voted to issue $2 million in bills of credit. Some delegates still held out hope that they could make peace with Britain, which led to the Olive Branch Petition in July, but King George III refused to even consider it.

The following year on July 4, Congress passed the Declaration of Independence, although it took some cajoling for all 13 colonies to vote in favor. As the war with Britain intensified, Congress realized it needed to form a national government that would set policy for all the colonies. The Articles of Confederation were agreed to on November 15, 1777, but they weren’t officially ratified until March 1, 1781, when Maryland became the last colony to approve them.

The Second Continental Congress continued to meet until March 1781, adjourning periodically and occasionally leaving Philadelphia when the British Army occupied the city. Congress was initially popular with the colonists, but as the war dragged on, it became less so. This is common with many new governments, as the hopes for change are narrowed by the need to chart a predictable path forward. A central challenge for this government was that the individual colonies didn’t always abide by the decisions of Congress, which led to skyrocketing inflation, which colonists blamed on Congress. Soon after Maryland approved the Articles of Confederation, the fighting with the British largely ended (the peace treaty wouldn’t be signed for another two years). The government established under the Articles of Confederation ended up being too weak to govern effectively, which set the stage for the U.S. Constitution later in the decade—but the 250th anniversary of that milestone is a little further in the future.

About the Author

J. Robert Parks is a former professor and frequent contributor to Gale InContext: U.S. History and Gale In Context: World History who enjoys thinking about how our understanding of history affects and reflects contemporary culture.