Following the death of Pope Francis on April 21, 2025, the Catholic Church entered a period of mourning—and transition. The death of Pope Francis and the election of his successor, Pope Leo XIV, is a rare opportunity to witness a global leadership transition informed by rituals that have guided the Church for nearly 2,000 years.

But behind the regalia and titles and church institutions are the lives of the men at the helm of the Catholic Church: Jorge Bergoglio (Francis) and, today, Robert Prevost (Leo XIV). Studying their lives invites students to consider how their backgrounds and beliefs shape their decisions, how those decisions impact institutions, and, in turn, how those institutions shape the world.

That kind of inquiry depends on access to trustworthy content—something Gale In Context: Biography and Gale In Context: High School are designed to provide. Instead of leaving students to sift through the click-bait and political agendas of search engine results, Gale In Context offers full-length biographical entries alongside archival records, multimedia, and primary documents. Everything is curated for academic use and updated regularly, giving educators confidence that students are working with accurate, classroom-ready material.

The Life and Legacy of Pope Francis

Jorge Mario Bergoglio was born in 1936 in Flores, Buenos Aires, to Italian immigrants who fled Europe during the rise of fascism. They had hoped to escape the violence and political extremism spreading across Italy, but the country they arrived in would follow its own path toward repression. After the fall of Juan Perón’s populist government in the 1950s, Argentina entered a prolonged period of unrest, cycling through economic collapse, a series of coups, and, eventually, a brutal military dictatorship.

Early Life in Argentina

It was within this volatile context that Bergoglio entered the Society of Jesus, better known as the Jesuits. Training in the Jesuit Order is long and exacting. During this process, members engage in rigorous academics that emphasize moral formation and social responsibility. That tradition of grounded, intellectually-engaged ministry shaped Bergoglio’s view of what the Church is for and whom it should serve.

By his mid-30s, Bergoglio had become Argentina’s provincial superior of the Jesuits, an appointment that placed him in a position of institutional authority just as the country descended into its darkest political chapter. In 1976, a military junta seized power and launched what became known as the Dirty War, targeting suspected dissidents through disappearances, kidnappings, and torture.

As head of the Jesuit order in Argentina, Bergoglio was responsible for guiding clergy and safeguarding communities. However, criticizing the regime outright could have endangered himself and those under his care. Instead, he avoided public confrontation, choosing to fulfill his responsibilities through efforts to shelter dissidents and broker releases.

A Bishop Among the People

After completing his term as provincial, Bergoglio became part of the diocesan hierarchy as auxiliary bishop of Buenos Aires in 1992, then archbishop in 1998. This episcopal work placed him in vulnerable communities, which deepened his connection to the city’s people. As a bishop, he became known for avoiding grand gestures in favor of consistent attention to the poor and the forgotten. He rejected the privileges of his office, preferring to ride public buses and spend time in the neighborhoods most in need.

By the early 2000s, Bergoglio had become one of the most prominent figures in the Latin American Church. As archbishop and later cardinal, he remained consistent in his approach, often speaking of the “field hospital” Church—one that meets people in crisis rather than waiting for them to arrive ready.

Still, few saw him as a likely candidate for the papacy. He had built his reputation on discretion rather than visibility and often avoided the spotlight surrounding more outspoken figures in the Vatican. However, in 2013, when Pope Benedict XVI unexpectedly resigned, the Church found itself in need of a leader who understood institutional weight but carried it lightly.

When Bergoglio was chosen on the second day of voting, it signaled a great number of firsts: the first pope from the Americas, the first Jesuit pope, and the first to take the name Francis. His chosen name honored St. Francis of Assisi, known for his radical humility and care for the marginalized.

Francis’s Papacy in Practice

Francis approached the papacy as a responsibility to remain near those at the edges of society, not above them. He spoke frequently of a “Church that is poor and for the poor.” His first act as pope reflected those intentions when he chose not to speak but to bow his head and ask the crowd to pray for him.

During a 2015 visit to Bolivia, he offered a public apology to Indigenous communities for the Church’s role in colonial violence, acknowledging the history of forced labor and cultural suppression once carried out in the Church’s name. Rather than defend the institution, he confronted that harm without qualification.

A year later, he visited the Greek island of Lesbos, where thousands of Syrian refugees were stranded in overcrowded camps. Their arrival had triggered a political standoff across Europe, and many were forced into legal limbo under an EU deal that prioritized border control over resettlement. Rather than delivering a formal statement from the podium, he walked through the camp and met with families. When Francis returned to Rome, he did so with 12 Muslim refugees aboard his papal plane, demonstrating what moral leadership could look like through action.

Francis also made it clear that the Church could no longer speak credibly if it continued to emphasize Europe as the center of Catholicism. He brought new voices to the College of Cardinals to address that lack of representation, hailing from underrepresented countries like Myanmar, Tonga, and South Sudan. They redistributed power inside the Vatican, broadening the perspectives of those who help choose future popes and who have a voice in setting the Church’s priorities.

The Conclave: How Does a Pope Get Chosen?

When the papacy becomes vacant, the Catholic Church calls a conclave to select the next pope. This process isn’t an election in the modern political sense, as there aren’t any public debates or official campaigns. Instead, cardinals of voting age (under 80) gather in Vatican City to cast secret ballots inside the Sistine Chapel. Voting continues in multiple rounds until one name receives a two-thirds majority.

Technically, any baptized Catholic male is eligible, but in practice, nearly all popes are chosen from among the cardinals. Informal front-runners—known as papabili—begin to emerge through discussion, often based on prior leadership roles or perceived ability to respond to current challenges facing the Church.

Today, the College of Cardinals includes members from more than 60 countries. That diversity means the outcome of a conclave is shaped not just by theology, but also by different regional challenges. The person chosen reflects which priorities the Church sees as most urgent.

Controversial Conclaves and Tumultuous Transitions

While most conclaves follow predictable patterns, some have taken unexpected turns—even bordering on the bizarre—while others reshaped the papacy itself.

897 – The Cadaver Synod

In one of the most infamous episodes in Church history, the newly-elected Pope Stephen VI put the corpse of his predecessor, Pope Formosus, on trial. The body—nine months deceased and dressed in papal vestments—was propped up in court and charged with violating canon law. After being found guilty, Formosus’s corpse was stripped of its papal garments, excommunicated, and thrown into the Tiber River.

1378 – The Western Schism

The most infamous breakdown in papal succession began when cardinals gathered in Rome to elect a successor to Pope Gregory XI. Pressured by angry Roman crowds to choose an Italian, they selected Urban VI, but his harsh reforms and volatile temper quickly alienated many former supporters. A second group of cardinals fled and elected a rival pope, Clement VII. For the next 40 years, two—and eventually three—men claimed to be the true pope, fracturing European loyalties and prompting the Council of Constance to restore unity.

1559 – Locked In and Starved Out

The conclave to replace Pope Paul IV dragged on for nearly four months, deadlocked between factions aligned with Spain and France. Cardinals were eventually locked in the chapel and denied food until they reached a decision. The resulting pope, Pius IV, was elected more by exhaustion than enthusiasm.

1978 – The Year of Three Popes

After the death of Paul VI, cardinals elected John Paul I, who died unexpectedly just 33 days later. A second conclave that same year selected Cardinal Karol Wojtyła of Poland—Pope John Paul II—the first non-Italian pope in 455 years.

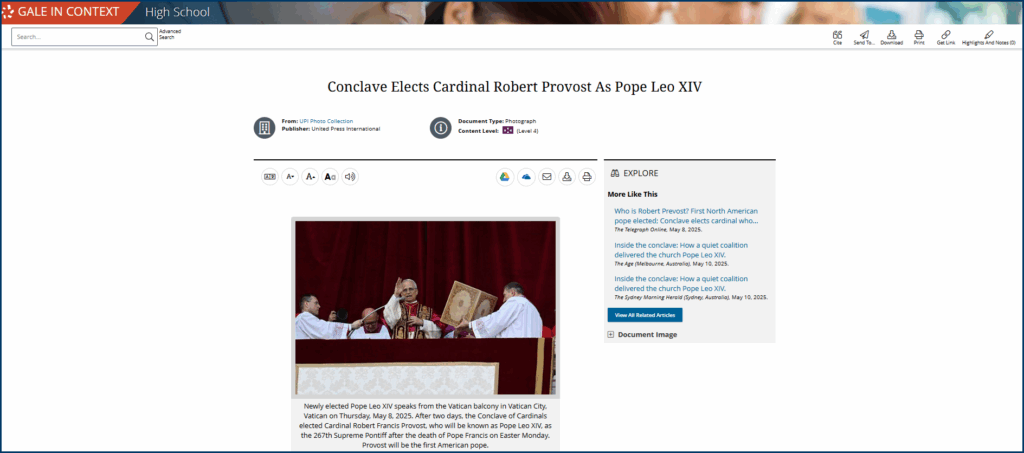

A New Papal Legacy Begins: Pope Leo XIV

Pope Leo XIV, born Robert Francis Prevost on September 14, 1955, became the 267th pope of the Roman Catholic Church on May 8, 2025. He is the first American-born pope and the second to hail from the American continents. He holds both US and Peruvian citizenship.

By becoming Leo XIV, he linked his papacy to Leo XIII, the 19th-century pope who issued Rerum Novarum, the Church’s first major encyclical on labor and social justice. That name suggests a vision of leadership grounded in engagement with the world, a value he spoke to during his inaugural mass, calling on the Church to build bridges through dialogue.

His election stirred pride among American Catholics, especially in his hometown of Chicago, where he was known simply as “Father Bob.” His election was met with joy and a sense of shared ownership in Peru, where he served as a missionary and educator for decades. He belongs to both places—and to a Church that is increasingly informed by cross-cultural experience.

Teaching Big Ideas Through Individual Lives

Pope Francis didn’t step into the papacy as a tabula rasa—a “blank slate.” He brought decades of experience, informed by political unrest in Argentina, his Jesuit foundations, and his work among the poor. So, too, will Pope Leo XIV bring his own context and convictions to the role.

In the classroom, historical moments like this invite students to ask what kind of experiences shape global leaders, and how those experiences affect the choices they make. Gale In Context: Biography supports those conversations by giving students access to educator-vetted life stories to develop evidence-based interpretations and think critically about public leadership.

Reach out to your Gale representative to request a free trial of Gale In Context: Biography and experience how it can support how your students connect with global and historical events.