Why can’t we have everything we want?

It’s a simple question, and probably one you’ve heard from your own students. Why can’t they buy both snacks? Why can’t recess last all afternoon? Behind those everyday frustrations lies scarcity, or the fact that there are always more wants and needs than there are resources to meet them.

When children experience the feeling of “not enough,” it’s unlikely that they’re considering the underlying economic principles. However, their daily decisions—such as whether to spend or save, share or keep—are examples of resource management.

With Gale In Context: Elementary, educators can use the American economy and economy topic pages to turn these everyday frustrations into lessons about scarcity and choice. These digital collections provide resources to introduce early financial literacy for K-5 students with trustworthy, age-appropriate explanations of core economic ideas.

The resources are created for children and reviewed by subject experts so that teachers can depend on their accuracy. The platform also features accessibility tools, including adjustable reading levels, text-to-speech, and translation into over 50 languages, which make the same content accessible to every learner.

The Building Blocks of Economics

At its most basic level, an economy is the system through which a community organizes and allocates its resources. Let’s consider some of the basics of how an economy works through a familiar setting for your elementary students: the grocery store.

Goods and Services

Walk into a grocery store and you’ll see the most basic elements of an economy at work: goods and services.

- Goods are the products on the shelves, like apples or a box of cereal.

- Services encompass all the work involved in delivering goods to the customer: The person who transports the food from the warehouse, and the worker who scans the barcode at checkout.

If we follow a particular good back toward its origin, it’s easy to see how intertwined the two categories truly are with one another. A farmer buys seed and fertilizer (goods) before planting and harvesting the crop (a service). They then sell the grain to a manufacturer, where workers oversee production (a service) and machines package it into a boxed product (goods). Each step layers one type of contribution onto another until the final product arrives in the kitchen cabinet.

Together, goods and services form the backbone of every economic exchange, whether it’s feeding a family or running a global supply chain.

Producers and Consumers

Economies also depend on the people who take part in commercial exchanges.

- A producer is anyone who creates a good or provides a service.

- A consumer is someone who benefits from a good or service, by purchasing it, using it, or both.

We all act as both producers and consumers every day. A cashier provides a service by ringing up customers’ purchases, but on the way home, they might fill their car with gas or order takeout.

The flow between producing and consuming is what keeps economies moving. Goods and services gain value only when someone chooses to use them, and consumers depend on producers to make these goods and services available in the first place.

Resources and Trade-Offs

Every exchange also depends on the resources available and the trade-offs they require.

- A resource is anything used to produce a good or service, and it can include physical materials, tools, time, money, and skills.

- A trade-off is the choice we make when limited resources—often financial, but also time, skills, or materials—force us to give up one option to take another.

At the grocery store, money is the key resource for a family shopping on a budget. That money is limited—this is what economists call scarcity. Scarcity means there is never enough of a resource to satisfy every want or need.

Money is a scarce resource. So, when choosing between free-range eggs or economy, a consumer might value the quality and ethics associated with the more expensive free-range eggs, but ultimately opt for the economy eggs in order to afford other goods they need from the grocery store.

Classroom Activity: The Community Economy Web

Invite students to name all the jobs they can think of in their community—teachers, farmers, artists, bus drivers, doctors, bakers, carpenters, musicians. Write each one on the board. Then, ask how each role provides something others use, such as the bus driver transporting children to school or an artist creating pieces that people enjoy in their homes or in public.

Next, ask how those same people also consume, and draw lines between roles using different colored markers.

By the end, the picture shows that everyone both gives and receives. Jobs create goods and services, but they also allow people to earn money to support their own needs and wants. The web makes the economy visible as a set of relationships where people depend on each other in many different ways.

Types of Economies

Once students have learned the building blocks of economics, the next challenge is applying them to entire systems. At the national level, questions about goods, services, and trade-offs scale up. The stakes are higher, but the logic is the same: limited resources force choices.

To decide how to use their resources to meet people’s wants and needs, every economy, regardless of size, must settle three questions:

- What should be produced?

- How should it be produced?

- Who should receive it?

The way societies answer these questions determines their economic system. Let’s take a look at three different models.

Market Economies

- What should be produced: Whatever consumers demand.

- How should it be produced: However producers choose, based on competition and efficiency.

- Who should receive it: Whoever can pay for it.

A market or laissez-faire economy is an economic system that relies on voluntary exchange: people and companies make choices about buying, selling, and pricing, and those choices interact to guide the flow of goods and services.

A simplified example of a market economy would be a local farmers’ market. Customers arrive wanting fresh strawberries, but there are only so many baskets available that day. If more families want strawberries than farmers have on hand, the price rises until only those willing to pay more buy them. If the season is abundant and stalls overflow with fruit, the price drops so farmers can sell what they’ve picked.

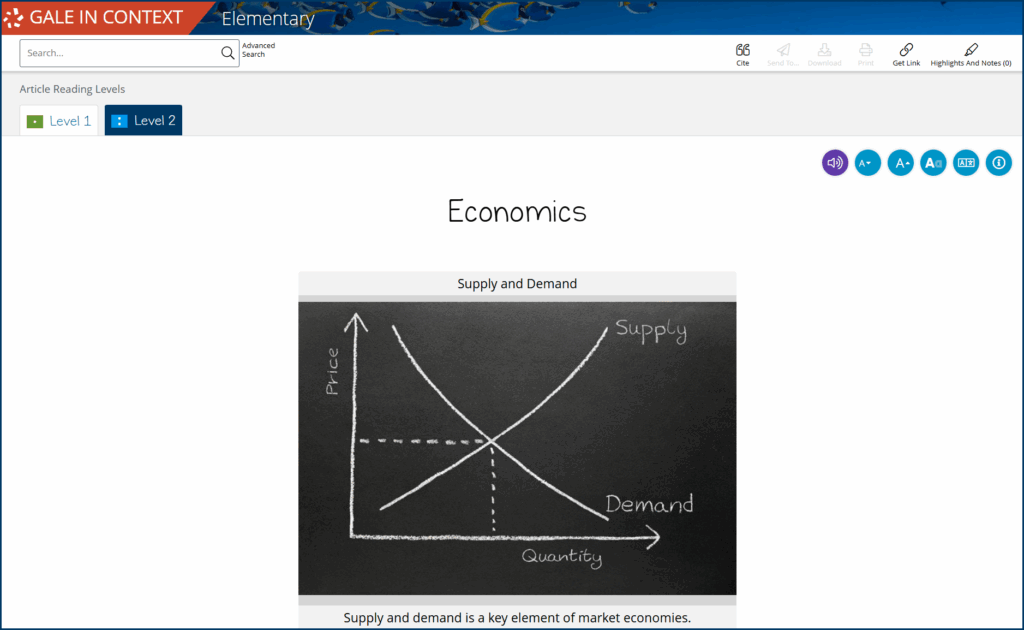

That back-and-forth is the core of supply and demand. Demand reflects how much people want a product. Supply reflects the amount that exists. Prices fluctuate to balance the two, sending signals to producers about whether to produce more, less—or to try something new altogether.

At the same farmers’ market, several farmers might be selling strawberries. Each wants customers to stop at their stall, so they might lower prices or advertise how they offer a sweeter variety. Shoppers, in turn, compare what’s available and choose what seems like the best choice. This situation—when more than one producer tries to win the same buyers—is called competition.

Competition matters because it changes how both producers and consumers behave. Over time, competition encourages producers to improve their products and use their resources more carefully.

Strengths and Limitations

Market economies respond quickly to what people want and often encourage creativity, which tends to make them very innovative. However, essential goods and services that don’t bring profit—such as clean water, public libraries, or affordable healthcare—may be overlooked. And because not everyone has the same income, consumers don’t all have equal power in the system.

Critical Thinking Questions:

- If people with more money can afford to buy more goods, how might that influence what products are produced and who receives them?

- How does competition between sellers (like two lemonade stands on the same street) help or hurt consumers?

- What are the risks of allowing supply and demand decide everything? Can you think of something important that might not get produced if it isn’t profitable?

Command Economies

- What should be produced: Whatever the government decides.

- How should it be produced: According to government plans and direction.

- Who should receive it: Whoever the government assigns goods and services to.

A command economy is an economic system in which the government takes responsibility for major decisions regarding production and distribution. Instead of supply and demand influencing what gets made or how much it costs, officials set prices, direct factories, and determine how the nation or community uses resources.

One historical example comes from the former Soviet Union. Farmers worked on state-owned land and followed quotas that dictated what crops to grow—such as wheat, potatoes, or corn—based on national plans. If the target required 10,000 tons of grain, then farmers have to meet that quota, even when conditions suggested another crop would be wiser. Shoppers then purchased rationed food in government-run stores at prices fixed by the state, regardless of availability or demand.

Strengths and Limitations

In a command economy, leaders can direct resources toward projects that may not always yield immediate profits, but serve national goals.

But the same system often struggles to match supply with what people actually want. Stores might be full of one item no one is buying, while families wait in long lines for another that ran out weeks earlier. Without the pressure of competition, producers also have little incentive to improve their goods, which can result in stagnant quality over time.

Critical Thinking Questions:

- If government leaders decide what should be produced, how could that make life fairer for some people? How could it cause problems for others?

- What happens when the government sets the same price for everyone, no matter how much people want the product?

- Why might leaders focus on building things like railroads or factories instead of toys or video games? What trade-offs are they making?

Mixed Economies

- What should be produced: Both individuals and governments decide.

- How should it be produced: Businesses compete, and governments set rules or step in where needed.

- Who should receive it: People often purchase many goods themselves, while governments provide or support some essential goods and services.

A purely market system risks restricting market access based on income, while a purely command system often struggles to respond to what consumers need or desire. Mixed economies, like that of the United States, develop when societies attempt to harness the advantages of both while mitigating their weaknesses.

Scarcity explains why these systems exist in the first place. Resources—money, time, labor, raw materials—are always limited, no matter the nation.

In a purely market-based system, families and businesses make their own choices about what to grow, build, or buy. In a command system, officials set the priorities. A mixed economy combines aspects of both. Families might decide which shoes to purchase, while tax dollars are directed toward public services, like roads, schools, or emergency services. The trade-off is the same in both cases: choosing one goal means setting aside another.

Strengths and Limitations

Mixed economies can make scarce resources stretch further without eliminating personal choice by supporting services—such as fire departments or libraries—that would be difficult to provide individually. Even then, scarcity never disappears, resulting in debates over which services deserve public investment, how much individuals should contribute, and which needs go unmet when resources are scarce. Regardless of the situation, there is always more need than capacity to give.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why are some choices better made by individuals or families, and others by the community or elected leaders?

- In some countries, services like healthcare and schooling are paid for collectively through taxes, where everyone contributes their share. How might that change what families can spend money on themselves, compared to paying directly for private services?

- Why do you think different countries make different choices about what should be public (shared) and what should be private (individual)? What values might guide those decisions?

Children learn quickly that they can’t always have every snack, toy, or extra minute of recess they want. Every society encounters the same challenges when it comes to scarcity, whether deciding how families spend their money or how governments invest in schools and healthcare.

Request information from your local Gale sales representative about Gale In Context: Elementary and how its K-5 economics resources are a scaffold upon which to build middle school topics, such as inflation and taxation, and eventually, high school discussions of globalization and economic planning.