Halloween taps into something ancient, permitting us to play with the things we’re usually told to avoid: darkness, fear, disguise—even death. The strangeness of the season seems to compel us to embrace the things that go bump in the night, just as those nights grow longer and colder.

Of course, teaching those themes comes with its own set of challenges. A quick Google search for topics like pre-Christian rituals, death traditions, or folklore can easily lead students down a rabbit hole of sensationalized or age-inappropriate content.

With Gale In Context: High School, students can follow their curiosity into Halloween’s history without teachers having to worry about what they might encounter. The platform brings together credible sources—scholarly articles, primary texts, and historical images—all curated for classroom use. It gives students the freedom to explore complex topics from multiple angles while giving educators confidence that the content is accurate and instructionally sound.

So, if your classroom is ready to cross the threshold, here’s a glimpse at what students might uncover via Gale’s Halloween topic page, beginning with the Celtic festival of Samhain and branching into Christian reinterpretations, Irish folk practices, American reinventions, and global parallels, such as Día de los Muertos.

Samhain, the Celtic Precursor to Halloween

The story of Halloween begins with Samhain (pronounced SAH-win), a Celtic festival that marked the return of winter and opened the door to much of what the holiday would later become. Samhain, observed from sunset on October 31 to sunset on November 1, was a liminal time, when the boundary between the physical and spirit worlds dissolved, and supernatural forces could move freely between them, bringing messages or mischief.

Communities responded with ritual, gathering on hilltops to light large bonfires. As the flames rose, many arrived in disguise—some darkened their faces with soot, and others wore carved masks or animal hides to confuse vengeful spirits. When the fire had burned down, each household carried that protection home. Hearths were extinguished, then relit from the communal flame, symbolically linking each home to one another.

Not all spirits could be outwitted, however. Some had to be appeased with offerings of milk and bread placed near doorways or burial sites. While some gifts were meant to comfort ancestral spirits, more malevolent forces were also believed to partake, especially the Aos Sí, a temperamental race of fairy folk. They demanded a darker version of “trick or treat,” where the cost of refusal could be soured milk, blighted crops, or illness in the home.

Critical Thinking Questions:

- What elements of modern Halloween can you trace back to Samhain? In what ways have these traditions been preserved or reinterpreted over time?

- Why do you think these rituals persisted, even if the supernatural beliefs behind them haven’t always been taken literally? What practical purposes might they have served in helping communities prepare for hardship, maintain social bonds, or explain the unknown?

Sanctifying the Season

By the eighth century, Christianity had gained a firm foothold across Ireland and Britain, but older beliefs and seasonal festivals still held sway. To strengthen its influence, Church leaders began adapting local traditions to fit within a Christian framework. Samhain posed a particular challenge. It marked a turning point in the agricultural year when harvests ended and communities prepared for winter. The rituals that accompanied it—honoring the dead, protecting the home, seeking guidance for the months ahead—were practical as well as spiritual, and too deeply rooted to be easily erased.

This strategy of adaptation had been encouraged centuries earlier by Pope Gregory I, who instructed missionaries not to dismantle local festivals, but to redirect them toward Christian meanings. Following that philosophy, Pope Gregory IV later moved All Saints’ Day—a feast honoring the holy dead—to November 1. It was paired with All Souls’ Day on November 2, which emphasized prayers for those in purgatory.

Together, these observances created a sacred window in the Christian calendar that mirrored Samhain in timing and tone. However, rather than anticipate spirits returning to earth, the faithful were encouraged to pray for the souls of the dead—no longer seen as earthly wanderers, but as departed souls in need of intercession.

Faith, Folklore, and the Space Between

Over the next millennium, Christian doctrine spread, but folk traditions held fast. By the later medieval period, parts of Ireland and Britain saw the rise of mumming, a practice in which masked performers went door to door offering short performances in exchange for food or drink. A related tradition, known as souling, emerged around the same time. On the eve of All Souls’ Day, the poor—often children—visited homes to offer prayers for the dead in return for small spiced cakes marked with a cross.

Over time, these communal customs gave way to more intimate, household-centered practices. Many Irish families still believed Halloween was a night when the veil between worlds grew thin, and they took steps to guard against what might slip through. Turnip lanterns were carved and placed near doorways to frighten off wandering spirits, a practice associated with the legend of Stingy Jack, who was cursed to roam the earth forever, his only light a burning coal placed in a hollowed-out vegetable.

Halloween also offered a chance to seek guidance from beyond the grave. Young girls played divination games to predict romantic pairings, tossing apple peels over their shoulders to reveal a suitor’s initial or reading shapes formed by molten lead dropped into cold water. Even sweets were believed to carry messages. Barmbrack, a fruit-studded bread, was baked with hidden tokens inside. A ring meant marriage; a coin meant prosperity. A thimble warned of spinsterhood, while a scrap of cloth signaled financial trouble.

These domestic rituals preserved the spirit of Samhain but shifted the focus from public to private observance, laying the groundwork for the smaller, household-based customs that would eventually accompany Irish immigrants across the Atlantic.

Critical Thinking Questions

- Why might the Church have chosen to reframe Samhain instead of abolishing it outright? What does that decision tell us about the role of tradition in shaping belief?

- When older traditions are adapted into new systems, how does that change their meaning? What aspects tend to survive—and what tends to be redefined or lost?

- How did Irish Halloween traditions reflect both Christian and folk beliefs, especially in how people viewed and interacted with the spirit world?

- In what ways do traditions like barmbrack or apple peeling reveal the social roles and pressures people faced—especially young women?

Halloween Crosses the Atlantic

When Irish immigrants arrived in the United States during the 19th century, they brought a hybrid version of Halloween with them. The bonfires were long gone, but the belief in a thinned veil—and the impulse to mark the season—saw the day retain its sense of inversion as a night when boundaries blurred and the unusual became acceptable.

What didn’t carry over was the communal structure that once gave the holiday meaning. In dense urban neighborhoods, Halloween became a night when young people gathered in groups, often without adult supervision. As is natural to children, that resulted in a bit of mischief-making. Without the guiding force of shared ritual, the energy of the evening had nowhere productive to go and increasingly turned toward pranks. Kids overturned wagons, soaped windows, and tied up streets with string. By the 1920s and ’30s, Mischief Night had become a fixture in many communities and a source of dread for adults.

In response, civic groups launched a coordinated effort to restore order, much like the Church had centuries earlier. Parents were urged to bring the festivities indoors, where games, sweets, and planned activities could help channel the energy more productively. Out of this push for order, trick-or-treating began to take shape. Drawing loosely from older customs like souling, it replaced prayers for the dead with a smile and a costume, exchanged for a treat at each door. The implied threat of mischief still lingered, but now it was easily tamed with a fun-sized candy bar.

After World War II, Halloween found a lasting home in American suburbia. Neighborhoods with tidy rows of houses made trick-or-treating safer and easier to organize, a fact that led to the holiday’s rapid commercialization. Candy companies seized the opportunity, promoting individually wrapped “fun-sized” treats that made participation simple for families. Costume manufacturers followed suit, expanding their offerings beyond traditional ghosts and goblins to include cowboys, princesses, and celebrities.

Critical Thinking Questions

- The idea of childhood as a protected and innocent life stage is a relatively modern concept. How might that emerging belief have shaped how communities responded to Mischief Night in the early 20th century? How do you think similar behaviors might have been treated in earlier periods?

- How did trick-or-treating balance the tension between preserving old customs and adapting to new cultural expectations in American cities and suburbs?

Día de los Muertos in Mesoamerica

Before Spanish colonization, many Mesoamerican cultures, including the Maya, Aztec, Zapotec, and others, had traditions for honoring the dead. They believed all souls were ongoing members of the community.

When Spanish colonizers encountered these practices in the 16th century, missionaries took their cue from earlier attempts to adapt Celtic holidays to Christian beliefs, aligning it with All Saints’ Day on November 1 and All Souls’ Day on November 2. Still, many cultures preserved the original meaning of the festival, continuing to treat it as a time for familial reunion across generations.

Welcoming the Dead Back Home

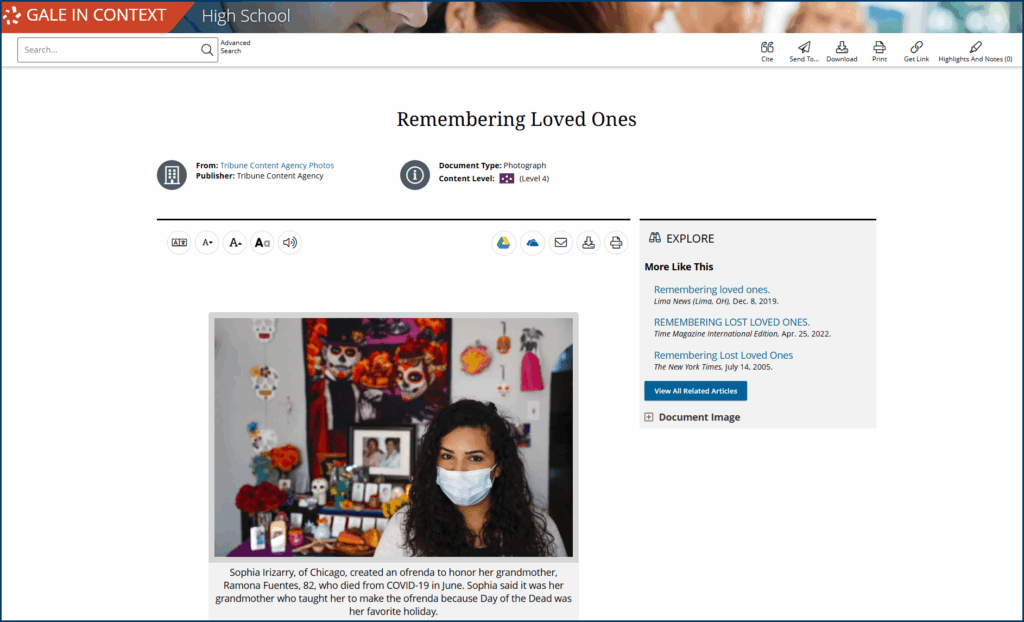

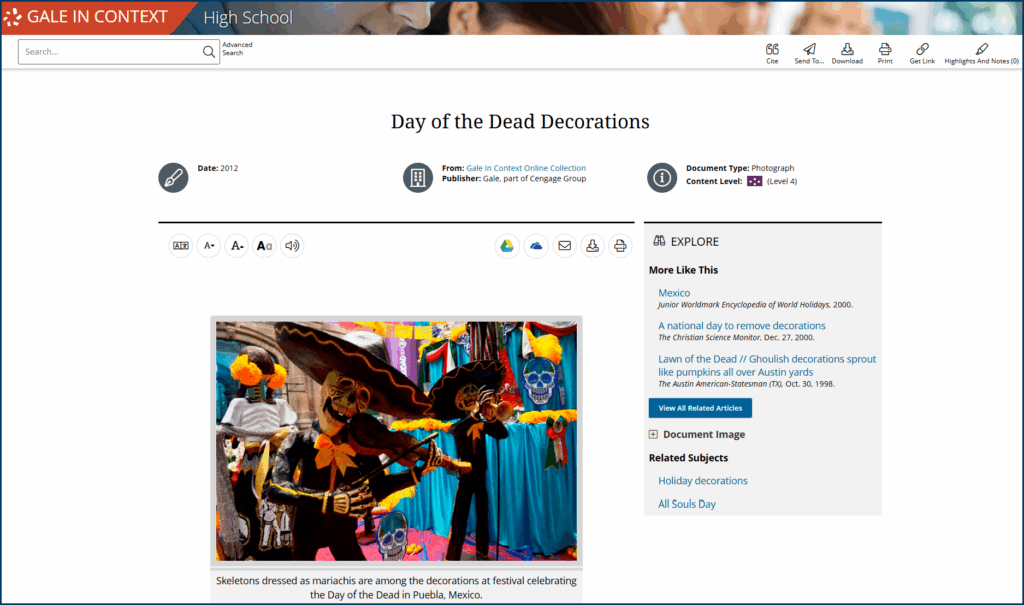

Today, Día de los Muertos continues to represent both Catholic and Indigenous elements, but the emotional center remains the same: remembering and reconnecting with loved ones who have died. In many communities, the celebration begins with weeks of preparation. Families build ofrendas (altars) in their homes or public spaces and fill them with photos, candles, paper marigolds, religious icons, and offerings like pan de muerto—a sweet bread decorated with dough “bones.”

Each item placed on the altar reflects a specific role in the act of remembrance. Papel picado, colorful banners made of tissue-thin paper, are a visual cue for movement between worlds. When it stirs, it’s a sign that spirits have arrived. Families and candy makers create calaveras, or sugar skulls, decorating them with brightly colored icing. Trails of marigold petals—cempasúchil—are arranged to guide spirits back with their bright color and distinct scent.

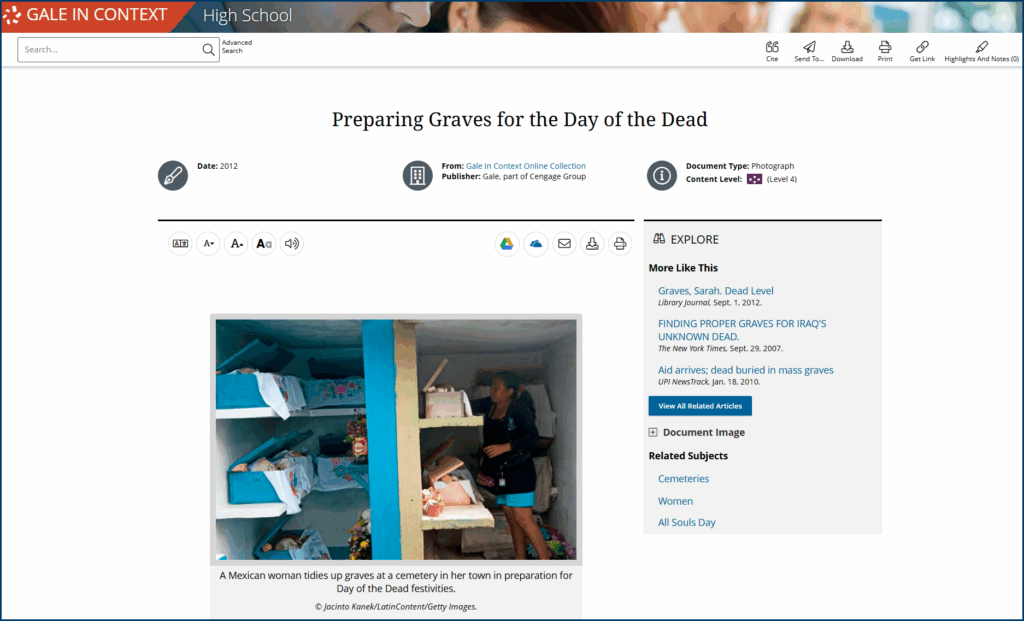

On the evening of November 1, families gather to clean graves, light candles, and leave toys, sweets, or small portions of favorite foods for los angelitos, or “the little angels” who have died. The next day honors adults. Families return with fresh offerings, and picnic near the grave site as musicians play. Both days stay busy, with people sweeping walkways and rearranging marigolds in anticipation of seeing their loved ones.

Critical Thinking Questions

- How does the way Día de los Muertos treats the return of the dead compare to the beliefs and practices associated with Samhain or Halloween? What do those differences suggest about each culture’s relationship to the spirit world?

- In many US communities, cemeteries are quiet, private spaces. What might this difference reveal about how each culture views death and the role of the dead in everyday life?

Getting students excited about Halloween is the easy part. Helping them think critically about it? That’s where we can help With Gale In Context: High School, students can trace modern traditions to their historical roots, explore how belief systems adapt over time, and examine how different cultures approach themes like death and remembrance. Whether they’re researching Samhain, souling, or sugar skulls, the platform supports deeper inquiry with trusted, curriculum-ready content.

Bring more substance to seasonal lessons. Connect with your Gale sales representative to learn about platform features and subscription options.