For thousands of years, the turning of the seasons has prompted communities around the world to ponder their mortality.

In ancient Ireland, Celts lit towering bonfires for Samhain, believing the flames would guide ancestral spirits home and keep harmful ones away. In China and parts of East Asia, the Hungry Ghost Festival calls for burning incense and paper effigies to provide comfort for wandering souls. In Côte d’Ivoire, the Fête des Masques brings entire villages together in masked dances said to connect the living with those who came before.

Perhaps the most recognizable example for American students is Día de los Muertos. At first glance, it can look similar to Halloween—there are sweets, costumes, and skulls. But its purpose is very different. Where Halloween often plays with fear, Día de los Muertos draws the departed closer, treating death as part of life’s cycle and making remembrance a joyful, communal act.

To understand Día de los Muertos fully, students need resources that go beyond superficial snapshots and generic summaries. The Gale In Context: Elementary, Middle School, and High School platforms bring the history, beliefs, and symbolism together in culturally informed, age-appropriate formats, helping educators present the holiday in ways that are both authentic and immersive.

Teaching Día de los Muertos in K-12 Classrooms

Students will approach Día de los Muertos with varying degrees of familiarity. In some classrooms, students will have helped set up altars with their families; in others, they may have only encountered the holiday in movies or media. Front-loading key terms at the start gives everyone a common foundation.

- Calavera – A skull; can refer to sugar skull candies or decorative skull imagery used during the holiday.

- Cempasúchil – Marigold flowers whose scent and color are believed to help guide spirits back.

- Fotografías– Photographs of the deceased, central to the ofrenda.

- Ofrenda– A home or community altar arranged to welcome back the spirits of loved ones, decorated with offerings such as photos, flowers, food, and candles.

- Pan de muerto – Bread of the dead, a sweet bread baked for the holiday, often decorated with bone-shaped pieces of dough.

- Papel picado– Pierced paper, colorful banners with cutout designs hung during celebrations.

- Recuerdos – Mementos or keepsakes that represent the life and personality of the person being honored.

- Velas– Candles, often placed on ofrendas or graves to light the way for spirits.

Pre-Columbian Festivals for the Dead

Long before the Spanish arrived in the 16th century, Indigenous peoples in Mesoamerica held annual festivals to honor the dead during the ninth month of their solar calendar—roughly late July to early August.

These observances reflected beliefs about the soul’s journey through Mictlan, the underworld ruled by Mictecacihuatl, the “Lady of the Dead.” Together with her husband, Mictlantecuhtli, she guarded the bones of the departed and watched over the spirits’ journey back to the world of the living.

For the Mexica (Aztecs), these rituals often took place at the close of the harvest, when fields and gardens yielded the maize, cacao, amaranth, and other ingredients for offerings.

Families prepared tamalli (tamales), xocoatl (choh-KWAH-tuhl), a cacao-based drink, and figurines shaped from tzoalli (tso-AH-lee), a dough of amaranth seeds mixed with honey or maguey syrup, to nourish visiting spirits.

They arranged these foods on ceremonial platforms or family altars in temples and homes, then led processions through fields and courtyards, scattering cempoalxochitl (sem-poh-al-SHO-cheet-l), marigolds, so their color and scent guided loved ones home.

Spanish Influence and the Shaping of New Traditions

When Spanish colonists and missionaries arrived in the 16th century, they brought the Catholic holidays of All Saints’ Day (November 1) and All Souls’ Day (November 2).

Rather than suppress the long-standing harvest-season festivals in July and August, missionaries redirected that energy toward early November by withholding church support for the summer observances. They encouraged churchyard gatherings, participation in processions, and incorporation of familiar Indigenous elements into the liturgy.

Linking familiar rituals to the Catholic calendar gave missionaries a way to promote their teachings without forcing people to abandon traditions entirely.

Modern Día de los Muertos Observances

Today, Día de los Muertos is celebrated across Mexico as a time when families honor the spirits of loved ones with the things they enjoyed in life, intended as a way to guide the spirits back to their families.

Ofrendas

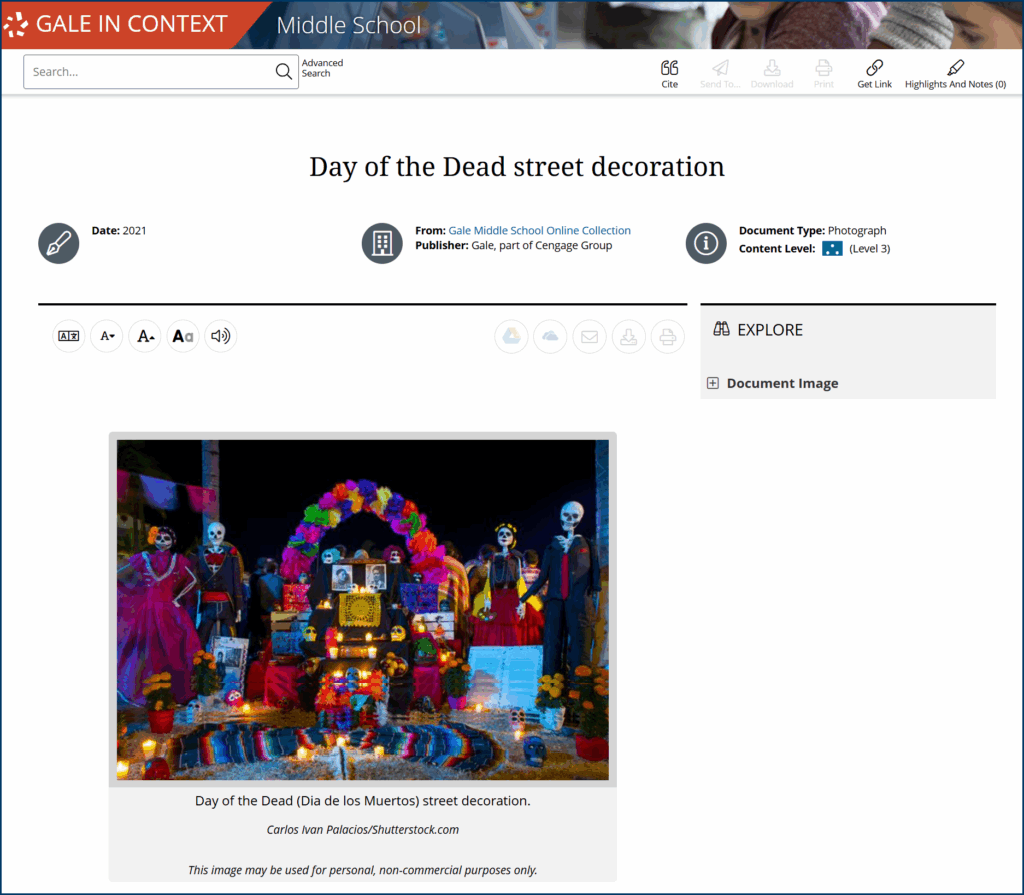

An ofrenda is the heart of many Día de los Muertos observances, whether set up at home, in a school, or in a public plaza. Some communities create large, collaborative altars where families contribute their own offerings; others focus on private spaces within the home.

Most ofrendas include items chosen for their symbolic meaning: water to refresh visiting spirits, salt for purification, candles to light the way, and papel picado whose movement represents the presence of the soul. Food is often specific to the person being honored—pan de muerto, favorite meals, or sweets for children—alongside photographs, clothing, or small keepsakes.

The tradition has roots in pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, where offerings at graves and temples sustained a connection with the dead. Catholic influences later introduced crosses and saint portraits, which blended with existing symbols.

Cempasúchil

In the weeks before Día de los Muertos, markets overflow with bundles of cempasúchil—bright orange marigolds whose name comes from the Nahuatl word cempoalxochitl, meaning “twenty flowers.”

The flower’s bright colors represent the sun, acting as a guiding light for the dead, while its scent draws spirits toward the offerings their families have prepared for them. During the festivities, the communities lay out petal trails from the graveyard, through the street, and into the house to direct the returning spirits to their altar.

Calaveras

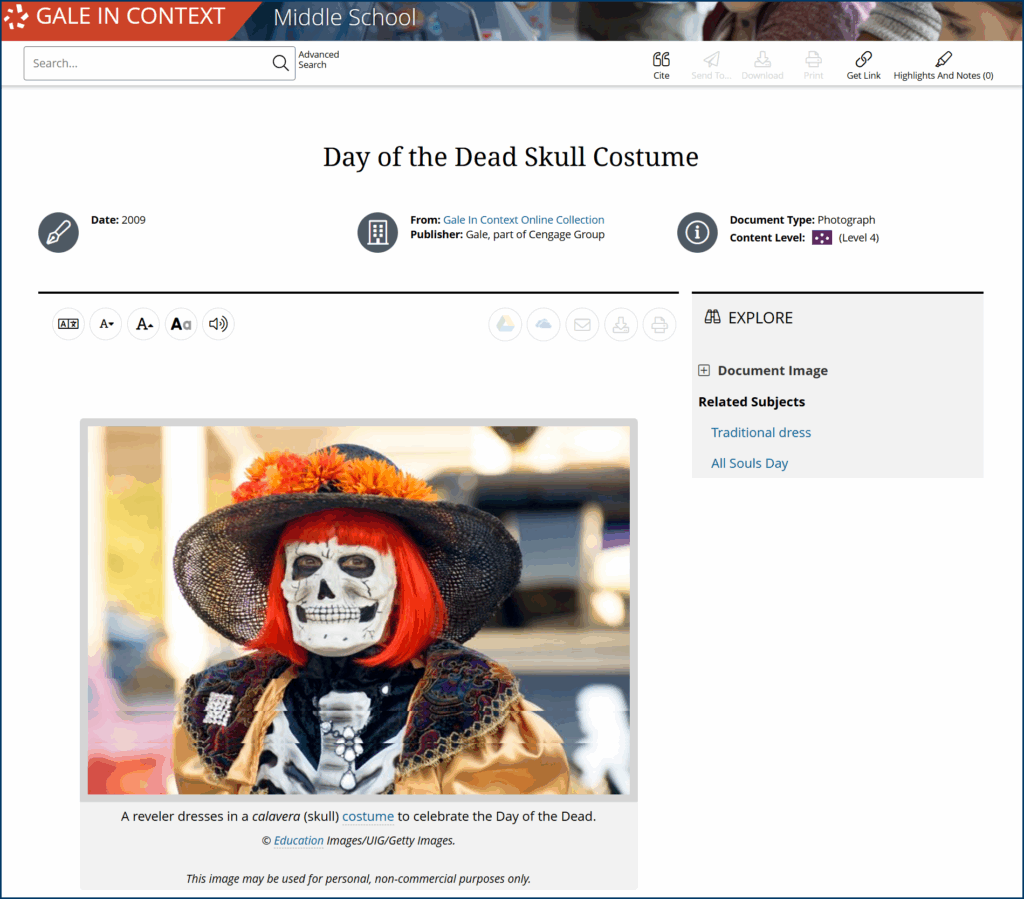

In Mesoamerican cultures, skulls often appeared in art and sculpture as a reminder that life and death are part of the same cycle. With the introduction of sugarcane by the Spanish in the 16th century, artisans eventually adapted the material into skull-shaped confections, decorated with colorful icing, sequins, and foil.

During Día de los Muertos parades, people often paint their faces in calavera designs. Some stick to simple bone outlines while others layer in floral motifs, hearts, and bright pops of color—reminders that death and life are inseparable parts of the same cycle.

Participants pair these motifs with traditional clothing. Many women wear long, embroidered skirts and blouses—called china poblana style—while men often dress in formal suits, complete with a marigold boutonnière.

Pan de Muerto

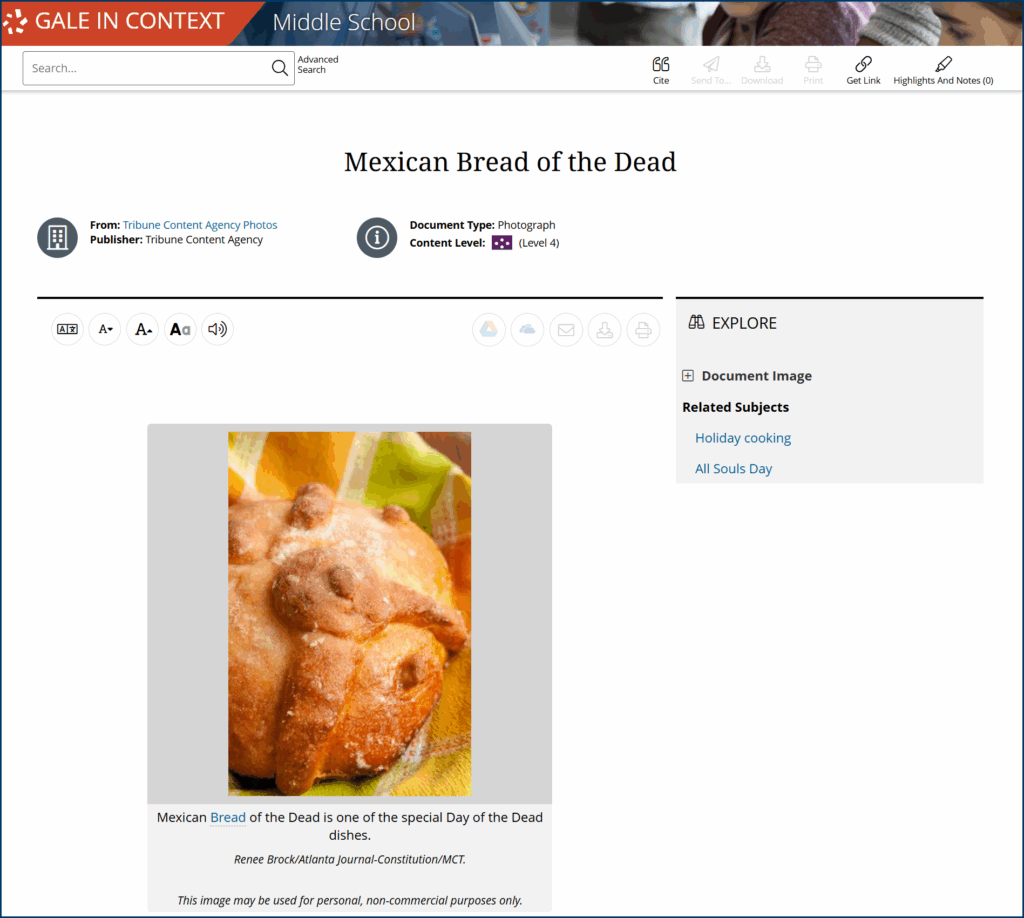

This round loaf, enriched with eggs and flavored with anise or orange blossom water, is topped with bone-shaped pieces of dough and a central knob representing a skull.

Variations appear across Mexico, sometimes dusted with sugar or sesame seeds. Families bake pan de muerto in late October to place on ofrendas and serve with coffee or hot chocolate during the holiday.

Grave Cleaning and Decoration

Families begin preparing for Día de los Muertos well before the holiday, making trips to the cemetery to tidy the graves of their loved ones. While grave cleaning and decoration is widespread, each community adds its own traditions and style.

For example, in San Andrés Mixquic, Mexico City, the evening of November 2 is marked by the Alumbrada, when thousands of candles illuminate the cemetery and families burn copal incense. Around Lake Pátzcuaro in Michoacán, including the island of Janitzio, communities hold all-night vigils, sharing food, music, and stories beside the graves.

For Elementary Classrooms: Sensory Immersion

For younger learners, concrete, sensory experiences make the cultural traditions of Día de los Muertos easier to connect with.

For example, tasting pan de muerto can move students from simple observation to interpretation. Associating the comforting taste and scent to feelings of love or remembrance helps students see that pan de muerto is a physical symbol of a loved one’s enduring presence. Its sweetness and warmth evoke the comfort of reunion, while the bone shapes acknowledge that death is not to be shunned, but embraced as part of life’s ongoing cycle.

With Gale In Context: Elementary’s Día de los Muertos topic page, students can begin with a sensory activity, using classroom-safe items to see, hear, smell, taste, and touch elements inspired by the holiday. Afterward, teachers can draw from the platform’s photographs, short videos, and introductory articles to explain the history and meaning behind each sensory detail, helping students connect their own observations to the celebration’s traditions.

Sight:

- Silk or paper marigolds in bright orange and yellow

- Photographs of ofrendas from different regions

- Papel picado in various colors and patterns

- Illustrations of calaveras

Sound:

- Recordings of poetry from calaveras literarias—playful, rhymed verses written in honor of the dead

- A recording of “La Llorona” performed by a mariachi band

- Snippets of son jarocho or huapango folk music

Smell:

- Mild incense sticks (unlit, for scent only)

- Orange slices or dried citrus peel

- Dried marigold petals

- Cinnamon sticks

Touch:

- Bright, embroidered fabric swatches to represent the china poblana clothing

- Dried corn husks (used in tamales and some decorations)

- Papel picado

Taste (if permitted and safe):

- Champurrado, a thick, masa-based hot chocolate

- Slices of fresh fruit, like mandarin or guava

- Small pieces of pan dulce

Discussion questions:

- How can each of the senses help us remember something or someone?

- What do the objects we interacted with today tell us about the values and beliefs of people who celebrate Día de los Muertos?

- If you were to make a remembrance space for someone important to you, which items would you include? Describe the sensation of each item—its image, feel, smell, taste.

For Middle School Classrooms: Regionally Specific Variations

By middle school, students can better understand how traditions vary across different places. Día de los Muertos works well for this, because the holiday doesn’t look exactly the same everywhere. In one town, music might fill the streets, while in another, families may keep the focus on quiet visits to the cemetery. These differences often come from local history, climate, or available materials—but the core belief of honoring the dead stays the same.

Using the Gale In Context: Middle School Day of the Dead topic page, students can work in small groups to research Día de los Muertos celebrations from different regions. Ask them to consider:

- How geography, climate, and local industries influence materials, food, and activities

- What the celebration looks, sounds, and feels like locally

- The historical and cultural origins that shaped it

Regional examples for research:

- Santiago Sacatepéquez, Guatemala – Residents launch giant, hand-painted kites called barriletes during All Saints’ Day to help guide spirits back to the living.

- Janitzio, Michoacán, Mexico – Families cross Lake Pátzcuaro by candlelit boat to spend the night at gravesides, singing and sharing food with the dead. (Note: Article is in Spanish, but Gale’s built-in translation tools make it easy to translate to English.)

- Huamantla, Tlaxcala, Mexico – Artists create intricate sand and flower tapetes (carpets) on streets, which serve as ceremonial paths for processions during Día de los Muertos and other celebrations.

- El Alto, Bolivia – Festivities include t’anta wawa—bread figures shaped like children or animals—shared between the living and offered to the dead.

Discussion questions:

- Which of the regional differences you found seem most influenced by local resources or environment, and which seem more connected to the community’s history or beliefs?

- How do the examples you researched show that a tradition can change in form but keep the same meaning?

- Think of another tradition you know from your family or community. How might it change if it were celebrated in one of the regions you researched? Which parts would likely stay the same, and why?

For High School Classrooms: Cultural Adaptation and Appropriation

The bright colors and striking imagery of Día de los Muertos often draw the eye first. In the classroom, that visual appeal can be an attention-grabber, but students gain more when they also learn what those symbols represent and why they matter to the people who use them.

But when sacred cultural symbols enter the mainstream, they can easily be misused. This has been a point of debate with several elements of Día de los Muertos, such as calavera face paint and marigold flower crowns, which hold deep traditional meaning but are sometimes used only for their aesthetic value.

High school students can examine where the line falls between honoring and misrepresenting these symbols, and how context shapes that judgment. Using the Gale In Context: High School Day of the Dead topic page, they can research:

- Primary sources (photographs, interviews, or event programs) showing the symbol in traditional settings

- Commentary from community members, scholars, and journalists

- Reference articles providing background on the traditions

To help students begin, provide them with case studies that reveal different sides of the conversation:

- Nike’s Día de Muertos Sneakers (Note: Article is in Spanish, but Gale’s built-in translation tools make it easy to translate to English)

- Day of the Dead Barbie

- Disney’s Coco

Examples of symbols to investigate:

- La Calavera Catrina – Political satire in early 20th-century prints by José Guadalupe Posada vs. feminist symbol in modern parades, fashion motif on Halloween costumes

- Marigold arches/pathways –Spiritual guide for returning spirits vs. decorative photo backdrops at shopping malls

- Sugar skulls – Handmade offerings on altars vs. mass-produced party favors

- Papel picado– Traditional cutwork that’s said to move in the breeze as spirits pass by vs. generic “fiesta” décor

From there, students can present an argument in either essay or video form that covers ideas like:

- What does this symbol mean in its original context?

- Does the modern use honor or appropriate the tradition? Support your reasoning with evidence.

- Based on your understanding of cultural preservation and adaptation, propose criteria that could help distinguish between honoring a tradition and exploiting it. How would your criteria apply to debates over Día de los Muertos imagery?

Día de los Muertos invites students to think beyond what traditions look like into why they matter and how they endure.

Bringing Gale In Context into your classroom equips learners with engaging, trustworthy sources that balance historical accuracy, cultural perspective, and age-appropriate presentation, so educators can feel confident introducing cross-cultural celebrations with curiosity and respect.

Contact your local Gale sales representative and request more information about how the Gale In Context database collection can support more authentic learning in your school.